Masks have disappeared everywhere, restrictions of all sorts (even inside hospitals) have been lifted, all information campaigns have been dropped and new ones not publicised. But Covid is still out there, and causing havoc.

In the past three weeks, according to the latest report by the Gimbe Foundation health watchdog, infections have almost doubled (+94 percent), hospitalisations have soared by 58 percent and in one month 881 people have died of the latest Covid variants. Each week roughly 60,000 people in Italy get infected.

Yet from officials, there’s silence. There’s no coordination anymore between regional health authorities handling vaccination hubs and family doctors (medici di base).

I only just learned today that in many regions, including Lazio where I live, the new 2023-2024 vaccination campaign launched last week, on December 4th, for all under 18s.

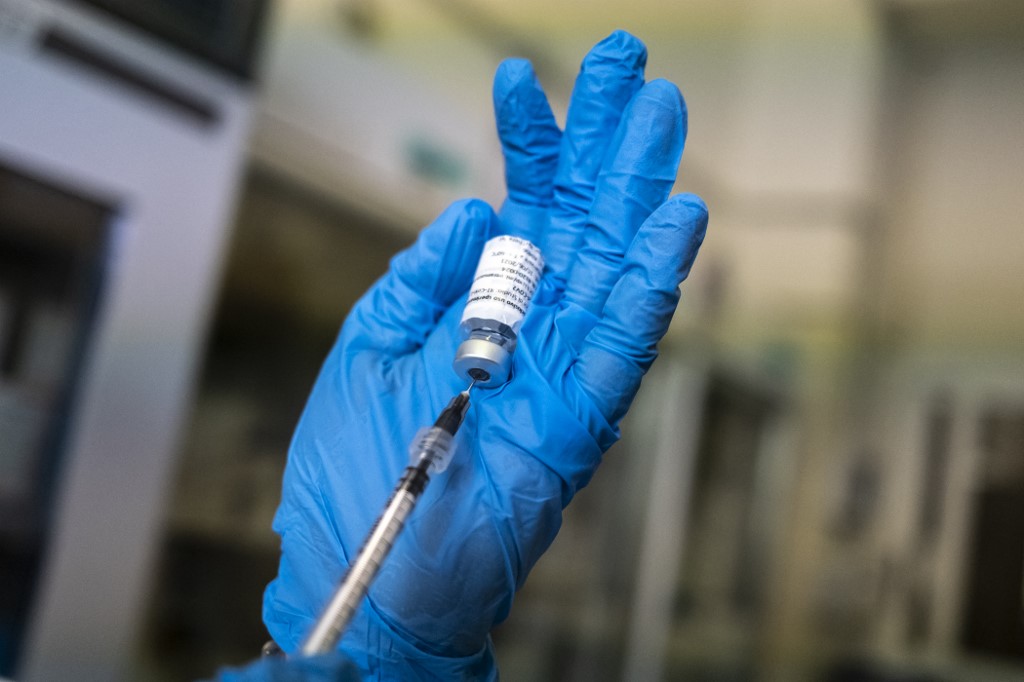

But somehow I missed it: there are no posters, leaflets nor hand-out material in pharmacies, private clinics, hospitals. My family doctor, who at the end of November gave me the yearly flu shot, said he knew nothing about it until two days ago. In a fit of panic, I rang the vaccination centre near my house and fixed jab appointments for my entire family.

READ ALSO: How to get a Covid booster jab in Italy this autumn

My neighbour this morning called me to complain: as she needs to regularly visit the doctor due to a chronic illness she suffers from, she had her flu shot at the end of November but then a week later caught Covid.

Her doctor knew nothing about the start of the new vaccination campaign, which are not merely ‘open days’ but regular dates on regional health authorities’ calendars for which an appointment must be fixed.

This new campaign is not being publicised, one needs to hunt on the internet and place calls to territorial hubs.

Now my poor neighbour has been told that given she has already caught the latest Covid variant, she needs to wait between three to six months for the new vaccine jab.

No wonder the 2023-2024 vaccination uptake has been really low. Just 1.2 million people in Italy have had the new injections, and the number has started to rise only in the last few weeks with roughly 190,000 jabs per week, mostly elderly people, and concentrated in Lombardy.

Last week, wearing an FFP3 mask, I stepped into an Italian hospital for a check-up: I was the only one wearing it. I was surrounded by patients with runny noses and coughs.

When I entered the elevator, I asked a nurse why. She replied, smiling: “Masks are no longer mandatory”. Yeah, but the virus doesn’t know that. I can’t believe how healthcare employees, including doctors and surgeons, don’t wear masks and have become so fatalistic. They are supposedly on the front line, protecting others.

This infuriates me, it is unacceptable. What have so many pandemic deaths taught Italians? Assolutamente niente! – or as my gran would say ‘un fico secco’ (a dried fig).

I think this is more than just a conscious choice to deprioritise new Covid waves by the health ministry. It’s a dangerous political move.

Policy-makers believe that as Covid has been around for four years already, and is weaker than at its outbreak, there’s no urgency, lest the risk of alarming people.

But winter has come, and the flu vaccine isn’t enough (last year I had double flu-Covid jabs at the same time).

Covid may not be as lethal anymore, with much milder symptoms, but it’s still debilitating. One year has passed since the last vaccination campaign, people get sick, can’t go to work, can’t look after their homes, and healthcare costs still rise.

I talked to a phone operator of the Lazio region vaccination campaign who told me that in the last five days hundreds of alarmed Italians and also expats have called asking for information, complaining of a lack of publicity to spread awareness and rushing to book the new jab.

He also told me that lately many medici di base are no longer entitled to vaccinate patients like they once did, which explains why many are clueless to what’s going on and the best way is to call the regional Covid centre.

Not just older people can book an appointment for a jab: also anyone who’s over 18 and had the last jab or infection more than six months ago.

If you happen to have caught the virus now, you can’t get the jab. The virus will be your ‘immunisation weapon’, which is far from reassuring as it can always lead to aggravated health conditions that can require hospitalisation.

Italy should make masks in hospitals compulsory again, just like Austria recently did after a surge in Covid infections worsened a medical staff shortage.

But politicians in Italy are keeping quiet. I really hope Italian TV and newspapers will launch vaccination information campaigns, particularly during the 8pm telegiornale evening news when families get together for dinner after work.

If no one spreads awareness, it’s like playing a broken record, and we’ll be back to square one.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

No surprise really. All media (yes, yours included) have created the ultimate ‘Cry Wolf’ affect. Nobody (of sane mind) gives a sh*t. But it doesn’t matter because the same thing is happening in many countries and people get over it. Unless they consume too much media. Please stop with the fear mongering.

“In a fit of panic” Hahhahahahahhahahahhahahahaha