Spaniards are known for being relaxed and laid back people. To some foreigners Spanish society can, at times, seem to move at a slower pace than elsewhere, though many view that as a charm.

Whether it’s the timekeeping habits, eating schedules, the (increasingly timeworn) cliché of siestas, or even just enjoying a well deserved day off, Spaniards have a reputation for knowing how to take it easy.

During the day in towns and cities across Spain, you’ll often see groups of colleagues enjoying a long coffee break or lunch together before heading back to the office. Though less common than they might’ve been twenty years ago, customs like these contribute to the stereotype that Spaniards like to take it easy at any opportunity.

But is this an entirely fair characterisation? Or do the clichés and stereotypes about Spanish society actually hide the truth about work-life balance in Spain?

The reality might surprise you. Spaniards work far more than many foreigners might assume (or believe they see) from their holidays, and there’s a reason that one Spanish politician said in 2023 that “Spain is experiencing a real work-life balance emergency. There are many people in our country who cannot reconcile their personal and professional lives.”

So, what’s going on? Does Spain really have a good work-life balance?

Working hours

A sensible place to start when assessing work-life balance seems to be working hours. Though it can appear that Spaniards spend all their time on the terraza, in reality they work more hours on average than their European counterparts.

Interestingly, the fact that Spaniards do take longer lunch and coffee breaks during the day might actually give the false impression that they work less, when in reality most Spaniards are returning to the office after those leisurely breaks and often staying there until 7 or 8pm or even later.

The data backs this up: Spanish employees work more hours than those in both the Eurozone and the EU: a total of 1,658 hours per worker in 2023, according to European Commission data, compared to 1,556 hours in Euro countries and 1,610 hours in the EU, respectively.

Yet OECD figures show that just 3 percent of employees in Spain work “very long hours”, roughly a third of the OECD average (10 percent), so the work-life balance is certainly better than in many countries.

In January, Spanish Labour Minister Yolanda Díaz has said her ministry will soon reduce Spain’s working week by two and a half hours to 37.5 hours (half an hour less a day) a decision which will improve the work-life balance of 12 million employees across the country.

Productivity

But the extra hours Spaniards work on average don’t necessarily translate into productivity in Spain. If anything, it seems to be the opposite.

Though each Spanish employee works 6.6 percent more hours on average than their European counterparts, Spanish companies produce 13.8 percent less than the EU average.

This negative correlation between productivity and hours worked isn’t an indictment on Spaniards themselves, rather the structure of the Spanish economy and work culture in the country, where some bosses still believe in the antiquated philosophy that more hours behind the desk equates to more work done.

“The problem of Spanish productivity is widely known and structural to our economic model”, Valentín Pich, President of Spain’s Consejo General de Economistas (CGE), told Business Insider.

If you were to measure monetarily how much one hour worked in Spain is worth in terms of production in that time (i.e. productivity in terms of GDP per hour worked, which is the most common way of measuring productivity among experts), the difference is stark: in Spain it is $53/per hour, compared to $61/per hour in the Eurozone, according to OECD data.

Paternity and maternity leave

In this regard, Spain’s work-life balance is a little better, as paternity leave rights have been boosted in recent years. It now stands at 16 weeks, in line with maternity leave.

Both paternity and maternity leave is fully paid in Spain, and an added perk for Spaniards is that they retain 100 percent of their salary without paying income tax on it, meaning that they actually make more money than they normally do.

How does this stack up compared to other countries? Well, Spain is something of a leader when it comes to parental leave. If we take Spain’s Mediterranean neighbours Italy, Italian fathers get just 10 days paternity leave (fully paid) while Italian mothers have a little more than Spanish mothers at 5 months (20 weeks) but at 80 percent pay.

In France paternity leave is a little longer (28 days) but still nowhere near Spanish levels. In Germany the standard paternity leave is just 2 weeks.

Of the major European countries, the only parental leave policies that rival or even surpass Spain seems to be Sweden, where the government doesn’t differentiate between paternity and maternity leave and instead allows couples to share 480 days (paid) between them.

In most states in the U.S, paternity leave is just 12 weeks and unpaid. At a federal level, there is no paid parental leave legislation, so it’s safe to say Spain’s work-life balance certainly beats out the Americans.

Balance for parents

Despite some pretty stellar parental leave offerings, when it comes to work-life balance for working parents, Spain doesn’t do so well.

Survey data shows that difficulty in balancing work and family life is one of the main reasons given by families for having fewer children than desired, which not only compounds Spain’s plummeting birth rate, but is also one of the factors contributing to the alarming risk of poverty or social exclusion of the child population in Spain, which is a staggering 32.2 percent.

READ ALSO: The real reasons why Spaniards don’t want to have children

Similarly, parents struggling to find a better work-life balance also accentuates gender inequality in the labour market, mostly because it is usually women who are forced to sacrifice their professional development to take on childcare responsibilities, which often means reduced working hours, part-time employment, leave of absence for care, and a loss of income in many cases.

Polling from Spain’s Equality and Employment Observatory shows that 67.8 percent of Spaniards feel they have problems balancing their professional and personal lives, a figure rises to almost 81 percent among working women.

64 percent of Spaniards say that they arrive at work tired every day, while 73 percent confirm that they feel exhausted most days due to the double burden of work and home responsibilities.

For context, 81 percent of Swiss and Belgian mothers believe it possible to balance work and family life, and 75 percent of Norwegian mothers.

Holidays

One thing that Spaniards do generally benefit from is a number of public holidays, which are organised at the national, regional, and municipal level.

As of 2024 Spanish workers get 14 public holidays in total. There are 8 national holidays, 4 regional, and another 2 to be chosen on a municipal level.

READ ALSO: COMPARE: Which countries in Europe have the most public holidays?

Around the rest of Europe, Spain’s on par with the better countries in terms of public holidays. In Italy workers get 12 or 13, depending on the region, whereas in Austria it’s up to 15 regionally.

Spain does better than Norway (10 public holidays) Sweden (9) and France (12).

In Ireland there are usually 9 public holidays and in the UK there are 8.

One Spanish custom that lends itself to a healthy work-life balance is that of the puente (literally meaning ‘bridge’) that Spaniards expertly use to create long weekends due to a public holiday falling near the weekend.

In terms of paid vacation leave, most contract workers in Spain get 25 days, on a par with other European countries such as Austria, Finland, Denmark and Sweden, and only surpassed by the UK (28 days) and France (30).

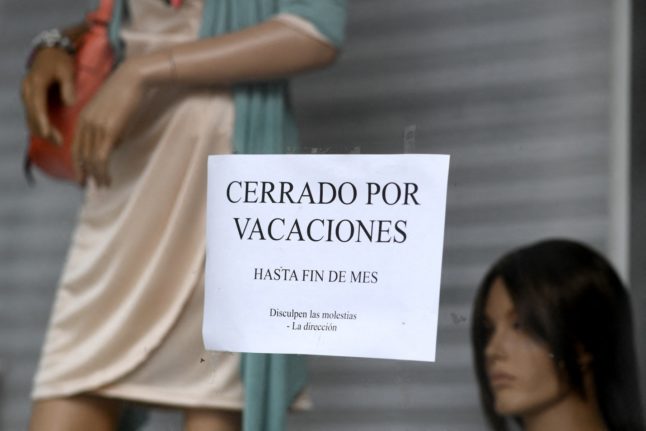

Therefore, Spanish salaried workers on average get a very decent amount of remunerated vacation days throughout the year, with the main setback being that many are expected to take the majority off during August.

A different story for Spain’s self-employed

Autónomos as the self-employed are called in Spanish work on average 9 hours a day (one more than the standard 8 hours for contract workers), according to Spain’s Survey of Working Population (EPA).

READ MORE: Long hours and little pay: What it’s like to be self-employed in Spain

It comes with the territory when you’re your own boss, whether it’s in Spain, the US or India, but in Spain self-employed workers also have to deal with complicated tax filing that results in many paying a gestor (a type of accountant/agent) to save them time and headaches.

They also don’t get to enjoy any of the paid annual leave that contract workers (asalariados) do. In essence, no work means no pay. At least when it comes to parental leave, mothers and fathers are paid by the State for four months an average of their monthly earnings over the previous six months.

Conclusion

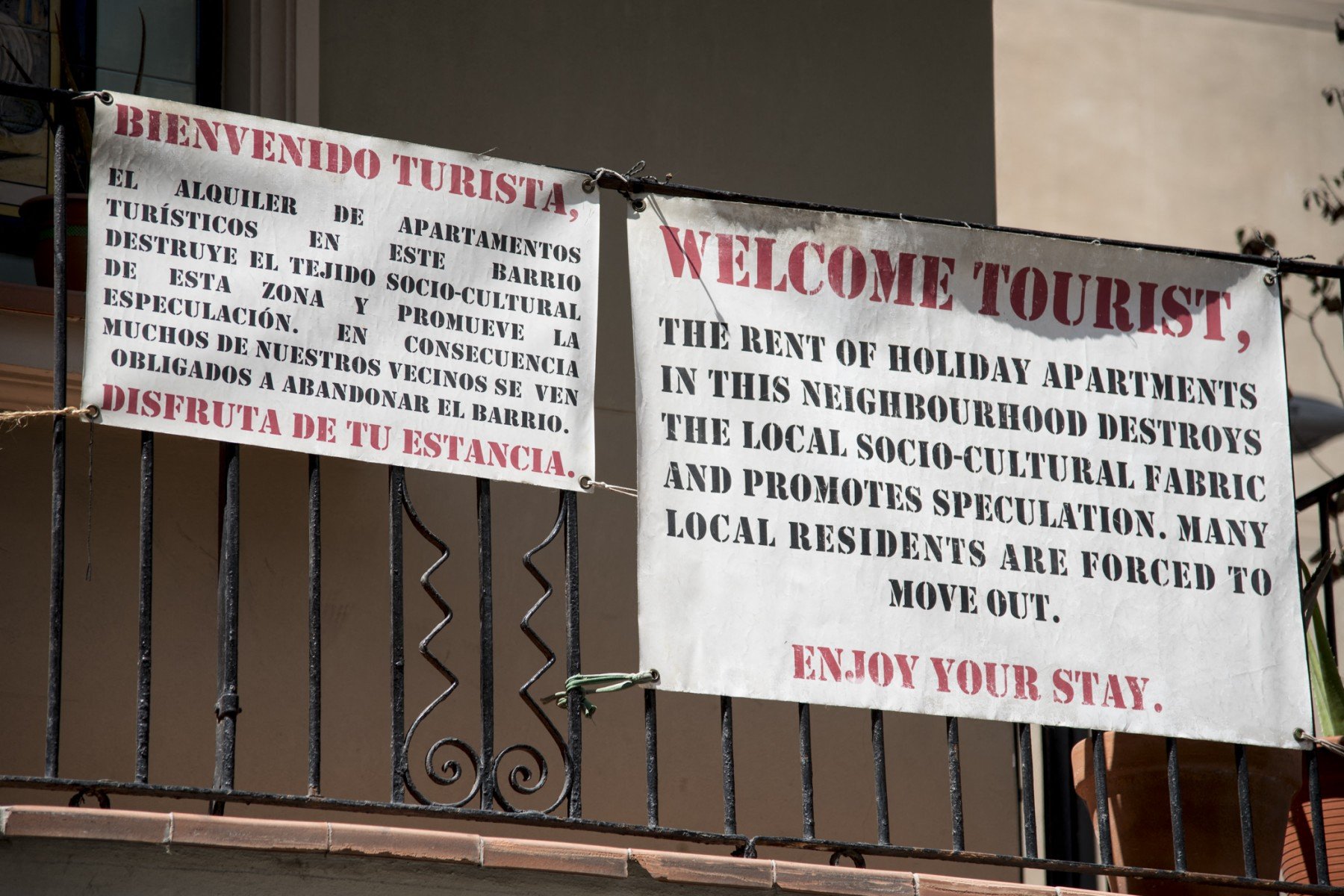

It’s certainly true that most Spaniards’ attitude to work is different to that of the work-obsessed US for example, valuing quality time with friends and family over money and job fulfilment, in part because the low salaries and lack of job opportunities in the country don’t warrant the extra commitment to their jobs.

A generous amount of paid annual leave and parental leave certainly add to the sense that Spanish workers (contract ones in particular) have a decent work-life balance, but for the self-employed, working parents and people in certain fields of fields of work this isn’t the case.

In fact, there’s currently a debate raging over whether people who work in bars, shops and restaurants end work too late (many clocking off from 10pm to 1am).

Things could be worse workwise in Spain, but it’s certainly time to put to bed the cliché that Spaniards don’t work long hours.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments