This month, 11-year-olds in Germany will receive a letter which will influence their future more than perhaps anything else. The “letter of recommendation” from their teacher decides more than anything else whether the children go on to study academic subjects or more practical ones.

Perhaps the biggest German success story in recent years, the BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine, might not have happened due to the inequalities of opportunity in this system. Uğur Şahin, a scientific genius to whom the human race will be eternally grateful, wasn’t recommended to Gymnasium. His teacher didn’t recognise his obvious intelligence and his parents didn’t know how to argue against this. If it wasn’t due to the intervention of a German neighbour, it is quite possible the BioNTech vaccine wouldn’t have happened.

When this story came out, a hashtag about being a good neighbour trended on German social media. But rather than being a good neighbour, wouldn’t an improvement be to get rid of an arbitrary system that can condemn bright children through oversight, luck, prejudice or malice?

READ ALSO: What parents should know about German schools

‘Disastrous’ for social mobility

This idea of streaming children into different schools based on ability may sound meritocratic, similar to the grammar school system beloved by many conservatives. But the German school system is grammar schools on steroids, and it has had disastrous results for social mobility; Germany has some of the worst in the developed world, with only 15 percent of young people whose parents didn’t go to university end up graduating from one, four times less likely than those with parents who did. It’s not just about education: Germany is second to last in the OECD in how many people rise from the bottom 25 percent to the top 25 percent economically too. Reports make clear these discrepancies aren’t just about the streaming system – low uptake in early childhood education and below EU average education funding also play a role.

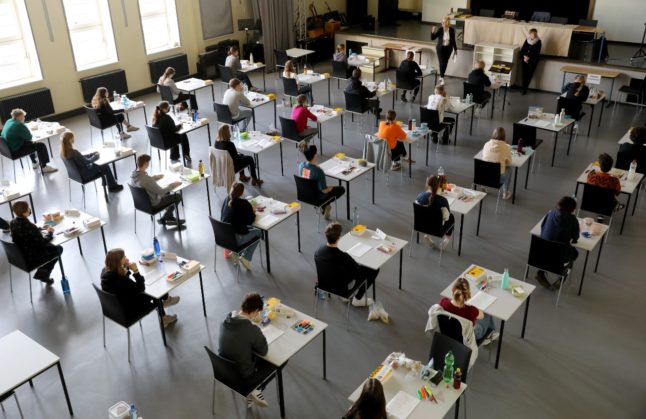

The school system differs slightly across each state but basically there are three types: Gymnasium, Hauptschule and Realschule. Gymnasium are the most academic and pupils go on to do Abitur, which is usually needed to get into university. Students can transfer from one to another, but by most accounts it isn’t easy. And while Gymnasiums and school streaming or tracking does exist in other countries, Germany has the strictest form of it.

PODCAST: The big problem with the German school system and can you pass a citizenship test?

Rather than being based on an exam such as Britain’s 11+ model (which itself benefits parents with the means to hire private tutors or the time and education to help their children study) it is based arbitrarily on the opinion of an individual teacher, who parents often make efforts to impress. Yes, teachers in Germany are highly trained professionals, but all people have unconscious biases and some people have conscious ones. Blind studies show that children with non-German or working class names like Kevin receive worse marks for the same piece of schoolwork.

It seems bizarre and unfair to make the decision at such an early age when children develop at different speeds – that’s if you need to make such a decision at all. Some of the school systems with the best results in the world such as Finland’s have a totally comprehensive system with no streaming at all.

Due to reforms in recent decades, the letter of recommendation is only compulsory in three German federal states, this isn’t necessarily a huge improvement. A 2019 study “The Many (Subtle) Ways Parents Game the System” showed how parents with more social capital, themselves usually white German and better-off, can get their children into Gymnasium regardless of grades and a letter of recommendation. Is giving pushy parents even more opportunities necessarily an improvement?

Supporters of the system say that not everyone is suited to academic study and we should allow for all kinds of different paths in life, and point to pretty decent income equality in the country. I agree, someone who gets technical qualifications being able to earn a decent living is something to be proud of in the German system, but why should that be determined by who your parents are? It doesn’t give working class people the opportunity to rise to the top – and changing careers in Germany is notoriously hard.

As it stands, the system appears quasi-feudal to an outsider, with people passing their societal position onto their children especially in a system where academic titles carry so much prestige that politicians plagiarising PhDs is a scandal. And while most middle class Germans I’ve met are pretty honest that their country could do more to integrate immigrants, there can be a pretty prickly response if you bring up class differences, despite the plethora of Von’s and Zu’s in media, politics and industry. I received far more backlash online with this topic than any other, from education professionals with academic titles galore. It made me wonder, if a teacher is going to relentlessly savage a professional journalist for expressing a critical opinion, how will they treat a misbehaving student?

German social mobility is terrible in large part due to the Gymnasium system, which decides your fate at age 11 without an exam, entirely on what your teacher thinks.

No wonder immigrant children rarely get a chance. BioNTech's Ughur Sahin didn't get accepted into one https://t.co/P94G5fftbd pic.twitter.com/07p9an6cnG

— James Jackson (@derJamesJackson) November 14, 2022

Education reforms are ‘controversial’

There have been attempts to introduce comprehensive schools or “Gesamtschulen” in various states, but they have hit major roadblocks from furious parents – one might argue they felt their privilege threatened. Education reforms are massively controversial in Germany generally. A striking proportion of Referendums and Citizen’s Initiatives across the country have been about repealing educational reforms, especially those which simplify the German language. No wonder approaching it is political suicide, mostly avoided even by progressive parties like the Left and the Greens. Educated people are a powerful constituency, with more money, representation and power. Meanwhile those disadvantaged are less likely to vote or even be able to vote.

READ ALSO: What foreign parents really think about German schools

For a country that styles itself as the Land of “Dichter und Denker” (poets and thinkers) it’s no surprise that Germany takes education so seriously. Education also played an important role in the development of the country as the so-called Bildungsbürger (member of the educated classes) gained a liberalising influence in the mid 18th Century. But the results weren’t always stellar. The so-called PISA shock of 2008 was the first time that students across Europe were compared with each other, and Germany performed poorly. Though the average attainment has improved since then, it still isn’t as spectacular as many Gymnasium fans think, scoring about the same as the UK which has mostly comprehensive schools, while scoring desperately low for equity in social backgrounds.

Education and what role the state should play in it is an emotive question. To me, it seems egregious that the state is funding a system that is shown to entrench social and educational inequality and segregate people based on what is more often than not their social class. The philosopher of science Stephen Jay Gould wrote “I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.” In Germany, he may have written that they were consigned to Hauptschule because of their name instead.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

This article hits close to home. We moved to Germany nearly 3 years ago and our oldest son struggles in school with 1 and 2 in Math, Science, and English, but 4’s and even a 5 in German and History. We recently toured a Gymansium near our house. It was clean, bright, and well furnished. Most of the parents there for the tour were white. We were told based on our sons grades to also tour the Realschule next door to be “more realistic”. We noticed suddenly that nearly all the parents and children were brown or black and from immigrant backgrounds. The school was darker, colder, and certainly less well appropriated. It reminded me of the inner city high school I attended as a youth in the USA. The difference being very clear however. I was a lazy student and struggled with ADHD. Around 16, I finally got my butt in gear and went on to earn a B.S. in Electrical Engineering and a Master’s in Cybersecurity Technology. I went from a childhood living in one room with my parents and siblings to having a home and a very comfortable life. It played through my head as the Director told the parents in the tour that many companies (manufacturing and service) came to get employees from this school. There was no place here for kids like me that were late bloomers. No place for my son who struggles with similar issues as I had. I thought, in the USA, he’d still have time to switch gears, but here, he was finished, set on the path to an assembly line at 11. We are very upset about this and it is one of the many reasons we are considering returning back to the States where you can write and rewrite your story as many times as you like.

I had two German girlfriends who both were tracked at age 11. One was geared towards becoming a worker in a Metzgerei while the other ended up in a business school to become a secretary. Over the years we kept in touch and in our 20s, both moved to the USA. The Metzgerei worker got her degree and became an RN. The other also got her degree and is now the director of a local business. Thankfully they left Germany at an early age.

I had a very different outcome in England, where I grew up and lived until I was 57. As the elder son of two teachers, I was always pushed towards passing my 11+ exam with the highest possible marks so that I could get into a grammar school. I found the effort needed to do this was not too difficult, because there was little else to do in the village where my father was the school’s headmaster, so teaching myself (by reading encyclopaedias and other books) kept me busy. There was no TV in our house, which was advantageous. My mother, who was a qualified ESN teacher, spent lots of time during my formative early years, teaching me the three R’s at home and I well remember her giving me a reading test when I was 7 and being told that I had a reading age of 19 … I wish I still had that!

I passed the 11+ within the top 2% in my county and went to a direct-grant grammar school as a result. That was an eye opener 🙂

I sort of lost my appetite for school work during my seven years at that school, not because the teaching was poor, but because my interests were narrow. Sciences and maths; the rest passed me by.