Last month the French Health Minister Olivier Véran warned of a “mega-wave”, in which infections from the Delta and Omicron variants of Covid would combine to produce record case numbers.

His prediction was correct – France is currently recording more new Covid infections than at any other point during the pandemic – with a seven-day average of 265,837 new daily cases last week.

Part of this can be explained by the fact that people are testing more now than ever before.

But for Pascal Crépey, a researcher at France’s École des hautes études en santé publique, it has more to do with the transmissibility of the Omicron variant, which is now the dominant strain in France.

“It has the ability to infect a much larger number of people than previous variants. It is very, very contagious,” he said.

“We were about to reach the peak of the Delta wave when the Omicron variant arrived. This is not a single wave, it is a double wave.”

What does this mean for hospitals?

The French government has previously enacted lockdowns when the intensive care unit became overwhelmed with Covid cases – so the situation in the country’s hospitals affects everyone.

Currently, the fifth wave hasn’t led to the same level of serious illness as previous ones.

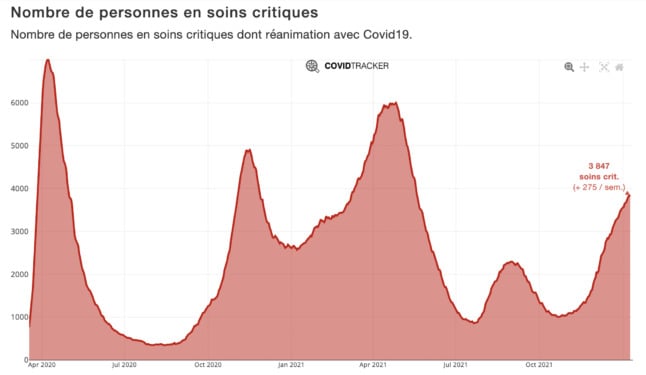

The latest figures show 3,847 people in intensive care with Covid-19 – a far cry from the 7,019 people in the same situation in April 2020.

France’s high vaccination rate is undoubtedly having an impact, but it seems that the Omicron variant is less likely to make people seriously ill than other strains of Covid.

But that doesn’t mean that we are in the clear yet – the graph above demonstrates that the number of Covid patients in intensive care is continuing to grow.

“Even if the Omicron variant is 50 percent less severe, but we end up with three times the number of infected people, we could have a much larger number of severe cases,” said Crépey.

Some hospitals have already seen their intensive care services become saturated.

Victorien Maginelle, a director at the Centre Hospitalier Compiègne-Noyon, said that this is the case in his hospital – where 70 percent of beds in these units are occupied by Covid patients.

“There is no more space for people who have heart attacks or road accidents,” he said.

“We have had to push back a lot of surgery. There are hundreds of patients waiting for an operation. There needs to be a space in réanimation following an operation, just in case.”

The impact of nearly two years of the pandemic is also beginning to take a toll on hospital staff themselves.

“We have people working 97 hours a week,” said Jean-Francois Cibien, an emergency ward doctor in the Centre Hospitalier AGEN-NERAC in south west France.

“We are exhausted. We cannot keep working like this.”

Outside of intensive care units, the number of Covid patients needing hospitalisation is growing at an even faster rate.

Like many working in the French medical sector, Cibien, who is also president of the APH medics union, believes the government has not done enough to support them.

“I would believe that our politicians would look at what happened in the three weeks over Christmas and that they would have the decency to extend the school holidays,” he said. “We just wanted one more week of rest. Resilience is dead. The French state has killed the resilience of its health staff. They are turning us into robots.”

A lengthy period of high occupancy rates in hospital will heap yet more pressure on medical staff.

So when will this fifth wave be over?

The head of the French Vaccine Strategy Council, Alain Fischer, predicted last week that the fifth wave will peak by the end of January.

“It sounds like a realistic scenario,” said Antoine Flahault, director of the Institute of Global Health at the University of Geneva. But he warned that infections could plateau, remaining at a high level, rather than peak and then begin to fall rapidly.

“We don’t have real examples yet apart from in southern Africa, where the situation has been improving dramatically in recent weeks. But it is not really easy to transpose that situation to Europe. In the South, it is the summer, so more people are outdoors,” he said.

The evolution of case numbers in the UK, which experienced a dramatic Omicron surge weeks before France, is a far better indicator for how things will go here.

“If the virus peaks in the UK, that would be a good sign,” said Flahault.

“Even if France avoids the most catastrophic situation, we can imagine that most sectors of the economy could be affected by absenteeism, even if people are sick for just a short period of time. This could include essential sectors, for about two to four weeks around the peak, but not for a long time.”

Could this really be the last wave?

The French Health Minister, Olivier Véran, gave an interview with some positive-sounding news to kick off the new year.

“This fifth wave will maybe be the last. The Omicron variant is so contagious that it will hit all the populations in the world. It will lead to a reinforced immunity. We will all be better armed once it has passed,” he told the Journal de Dimanche.

Unfortunately, many epidemiologists are not so sure.

“I don’t know why he said that. I think it was a little bit of wishful thinking rather than a scientifically-grounded comment,” said Crépey.

“Epidemiologists have known for quite some time that this coronavirus will not go away. There is no reason for it to go away. What is sure is that the engine for the creation of new variants is replication of the virus.

“When it replicates, it mutates. The more cases that you have the more opportunity that the variant has to mutate and create a new one with better ability to spread. The more we gain collective immunity, the greater the evolutionary pressure will be on the virus to escape this immunity”

Flahault said that while some of his colleagues agree with Véran, the more pessimistic outcome evoked by Crépey is also possible.

“Maybe a new variant will escape cell-mediated immunity. Maybe other variants will be more transmissible. We will see at the end of the day whether this Omicron strain has affected 40 percent of the population in Western Europe and whether this causes significant damage. If that is the case, we will need to find solutions.”

“I am strongly advocating that we think about air quality of indoor settings: it will fight against all variants to breath better quality air. The locations where we are infected today are indoor, poorly ventilated, crowded spaces. 99 percent of infections are known to occur in these locations. We acquire the virus in poorly ventilated spaces”.

How does vaccination help?

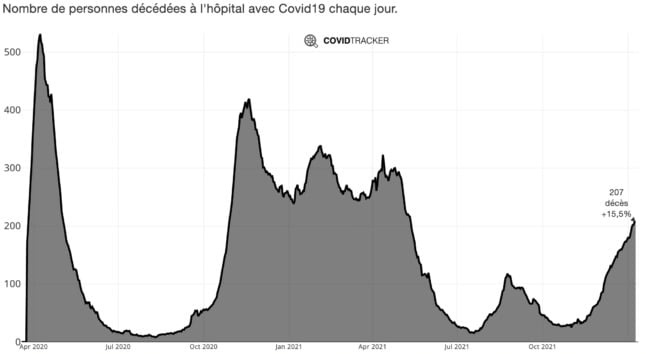

The number of people dying from Covid-19 is far lower than during previous waves.

While some of this can be attributed to differences in the Omicron variant, data from hospitals show that around 80 percent of Covid patients in intensive care are unvaccinated. Of the remaining 20 percent, the vast majority have suppressed immune systems through previous illnesses.

The number of Covid deaths recorded in hospitals is lower now than during previous waves. Source: covidtracker.fr

France has a high vaccination rate with more than 90 percent of the eligible population – and 78 percent of the total population – vaccinated with at least one dose. However, the fact that case numbers are exploding has knocked public confidence in the vaccination programme according to Crépey.

“This wave has made things very different in terms of public perception. When vaccines arrived at the beginning of the year, a lot of people thought it would be the end of the story for the Covid-19 pandemic. It was a mistake from the politicians and the scientists to oversell the vaccine,” he said.

Despite this, Maginelle warned of the dangers of forgoing vaccination, noting that those in intensive care with Covid where overwhelmingly unvaccinated.

“Last week, we had a 30-year-old man come into the hospital with Covid symptoms. He told us that he was fully vaccinated but is now in intensive care.

“We later learned that he was using a fake vaccination certificate,” he said.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Now that 12-15 year olds are eligible for a booster in United States, when will France offer the same to children here?