For three centuries, the venerable Académie Française in Paris has produced state-sanctioned dictionaries that document and approve new terms or expressions.

The first version dates back to the 17th-century creation of the Académie, while work on its latest tome, the ninth, has been underway since 1986.

READ ALSO Swords, immortality and wifi – 5 things to know about the Academie française

The backers of the new dictionary, which include French President Emmanuel Macron, are lightning quick in comparison and hope to reach many more people with an online resource based on the Wikipedia model.

“This dictionary will enable everyone who loves our language, and there are 300 million who speak it today, to appreciate its richness,” Culture Minister Roselyne Bachelot told a launch ceremony on Tuesday.

Called the Dictionnaire des Francophones (The Francophones’ Dictionary), it was proposed by Macron in 2018 as a way of bringing together and celebrating the diversity of modern French – which is an official language in 32 countries.

So far, it contains around 600,000 terms and expressions, Bachelot said, but users across the world have been invited to submit suggestions that will be vetted by other users and a team of linguists.

Apart from the works of the Académie Française, only one other dictionary has been ordered by the French state: the Trésor de la Langue Française (the Treasures of the French State), by President Charles de Gaulle in 1962.

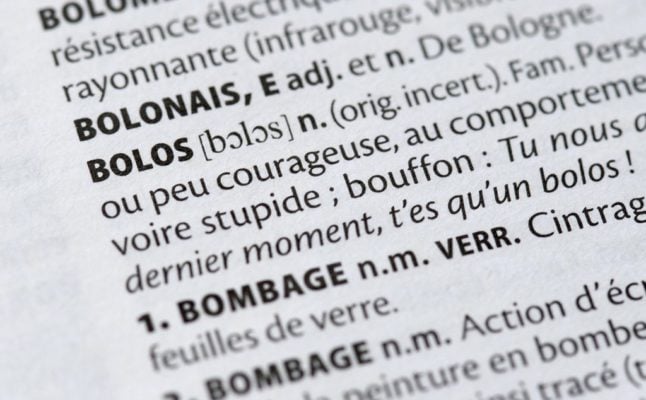

Other commercial French dictionaries, such as the Le Petit Robert and Larousse, are regularly updated.

The project reflects how France is home to a minority of modern French-speakers, with the language more commonly used in the fast-growing populations of former colonies in Africa.

In a speech in 2018, Macron broke with tradition by saying that France needed to acknowledge that it did “not carry the destiny of the French language on its own.”

“France must take pride in being ultimately a country among others which learns, speaks and writes in French, and it’s this decentralisation that we need to re-think,” he told an audience at the French Institute, which houses the Académie.

Macron has not given up on the global language battle, however, with the French president keen to increase funding for French language schools globally, and challenging the use of English in the European Union.

Bernard Cerquiglini, who was asked to lead the dictionary project, told the magazine Express that the dictionary aimed to bring together online resources from Africa, Belgium, Quebec and others.

“We’re building. We’re going to include little by little everything that exists on the internet on the French language,” he said, adding that the dictionary could reach one million entries.

Results given to a user will depend on their location, which will be detected by the search engine, meaning that a word like “baton” would show as golf club in Quebec, a cigarette in Senegal, or a penis in Ivory Coast.

“The idea is to create a dictionary of world French, and decentralised,” Cerquiglini added.

Louise Mushikiwabo, the head of the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), which groups French countries, proposed adding the word “techniquer” during Tuesday’s ceremony, which means finding an ingenious solution on a budget in Rwanda.

Cerquiglini replied that it would be added in the afternoon.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments