Spain and Portugal are neighbouring countries with a lot in common: the weather, the culture, their Latin-based languages, and both welcome an abundance of English-speaking tourists to their shores every year. Where the two countries differ rather significantly, however, is in their ability to communicate with those holidaymakers.

That is to say: the Portuguese are generally known for speaking very good English, whereas the Spanish are known for not speaking much at all.

Of course, Brits, Irish and Americans (and other tourists who communicate in English abroad, for that matter) should make an effort to pick up a bit of the local lingo when on holiday. But the reality is that many don’t, and rely instead on locals having enough English skills to survive.

But in Spain, besides tourist-focused certain resorts on the coasts and well-educated younger people, the level of English isn’t quite as good.

In fact, the Portuguese are the champions of southern Europe when it comes to English skills, according to rankings from Education First.

READ ALSO: 17 hilarious Spanish translations of famous English movie titles

The table was topped by the Dutch, with a score of 70.72, and among the countries considered to have a “very high competence” in English is Portugal, coming in 12th position overall, with 63.14 points. To find Spain, however, you have to go down to 35th place, grouped among countries with “moderate competence”.

Other ranking such as the new English Proficiency Index (EPI) have reached similar conclusions, ranking Portugal in 9th position and Spain in 35th in 2022.

So what are the reasons for the stark differences in English proficiency between both countries?

According to experts, Spaniards’ difficulty learning English can be explained by a number of factors, mainly the size of the country, the number of people who speak Spanish worldwide versus Portuguese and, of course, Spain’s obsession with dubbing every film and TV show.

READ ALSO: Why are the Spanish ‘so bad’ at speaking English?

To dub or not to dub

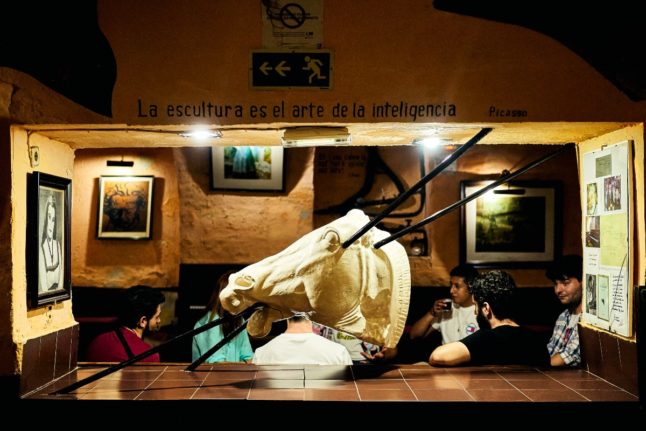

Rita Queiroz de Barros, head of the research group in English Linguistics at the University of Lisbon, told El Confidencial that “there is an explanation [for the gulf in English language skills] that I think is unequivocal and that is the preference that in Portugal was always opted for subtitles instead of dubbing.”

In Spain, on the other hand, just 4 percent of Spaniards who go to the cinema choose to watch the original version with subtitles. Figures from the Federation of Spanish Cinemas (FECE) from 2015 show how out of the roughly 3,500 large screen cinemas in Spain, barely 200 of them showed international films in their original language.

Much of Spain’s reliance on dubbing as opposed to subtitles has its roots in history, specifically in its dictatorial past. During the early stages of the Franco dictatorship, it was compulsory for all films to be dubbed into Spanish. The Language Defence Law, introduced in 1941, was used to strengthen Spanish nationalism by promoting Castilian Spanish through a mass cultural mode like cinema.

But the post-WWII Portugal of dictator Salazar went the other way. In order to guarantee what was “authentically Portuguese”, a 1948 law banned Portuguese cinema from being dubbed, also as a means of keeping the population in ignorance (in 1940, 52 percent of Portugal’s population didn’t now how to read and write).

However, in practice this had the adverse effect as several generations of Portuguese people grew up watching cartoons and films in English, consolidating their understanding of the language at an early age, improving further as literacy levels increased. Even though Portugal’s dictatorship ended in 1974, it wasn’t until 20 years later that Portuguese people were able to watch the first Hollywood movie dubbed into Portuguese – The Lion King.

READ ALSO: Why does Spain dub every foreign film and TV series?

As such, Spaniards in the second half of the 20th century have had far less exposure to English compared to the Portuguese. Queiroz de Barros argues the Portuguese tendency to listen to native language films with subtitles “was decisive because it exposed the Portuguese to English much more often and much earlier… [something] absolutely fundamental for this greater availability to learn English.”

Smaller countries punching above their weight

The relative size of the countries also plays a role, as there’s a tendency for smaller countries to perform better in foreign languages.

Antonio Cabrales, a professor at Carlos III University in Madrid who researches English teaching in Spain, told VOA News, that smaller countries are often forced to open up to the rest of the world to a greater extent and therefore must pick up more English — the international business language.

“Smaller countries like Portugal, Greece and Holland are more dependent on exports which means the population will have to travel and need English to conduct business. Larger countries with a bigger domestic market will not have to worry so much about this.”

Spanish speakers worldwide

Equally, the number of Spanish speakers in the world might also play a role. In fact, in this sense Spaniards could be guilty of the same (admittedly lazy) logic as many native English speakers: if millions of other people also speak my mother tongue, why would I bother learning another?

Spanish is the fourth most-spoken language in the world after English, Mandarin and Hindi. Almost 600 million people speak Spanish across the globe, according to a report published the Cervantes Institute, and it is the main language of an entire continent.

Portuguese, on the other hand, has around 230 million speakers and is only spoken in Portugal, Brazil, and several other smaller countries like Angola and Mozambique.

Perhaps there is something to this. If we consider other countries renowned for having high levels of English, say Sweden, Denmark, Holland or Iceland, all are relatively small countries with languages not widely spoken abroad. Like the Portuguese, these countries have more incentive to learn English – the lingua franca of the international community.

READ ALSO: And the Spanish leader with the best English is…?

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments