Based on recent arguments between the UK and the EU over vaccine supplies, nationalism has reared its ugly head again. The UK media focused on the EU’s threat to invoke Article 16 of the Northern Ireland protocol and barely mentioned that prime minister, Boris Johnson, had threatened to do the same, in parliament, two weeks previously.

Thankfully, the EU’s mistake was quickly recognised, publicly acknowledged, and reversed. As a result, the EU is now promised supplies from UK factories, to arrive in the first quarter of this year. The irony is lost on Brexiters that the EU threatened the NI border for just five hours, while the UK did the same for five years.

Vaccine supply is an issue for many countries, although less so for the UK. Having approved the use of various vaccines ahead of other countries, the UK was early to sign contracts with vaccine producers. As a result, the UK has rolled out its vaccination programme at a staggering – and for once, actually “world-beating” – pace.

Last weekend, a record-breaking 600,000 people were vaccinated across the UK. This was a phenomenal achievement by any standard, and is thanks to the incredible dedication, planning and hard work of the NHS. I cannot help thinking: how many lives would have been saved by giving the NHS the contracts for other programmes, such as test and trace, rather than handing them to private companies with ties to the Conservative party, and no relevant experience.

Based on announcements about the vaccination programme in Spain, and being in Group 4, I anticipated receiving my first jab around Easter, the second dose by the end of April, and to be immune by the end of May. Although I’m disappointed by the delay, I’m relieved to hear that cancellations for appointments related to supply problems are for the first dose, and not the second.

While the UK boasts about its vaccination rollout, it doesn’t mention those people who are awaiting their second jab. The UK has made a strategic decision to delay the second vaccination for up to 12 weeks, going against scientific advice. The vaccine producers have recommended that the second vaccine is ideally delivered three weeks after the first. Although some leeway exists, it is recommended not to exceed 42 days between doses.

The UK government has unilaterally decided that doubling that time to 84 days is acceptable, safe, and effective, minus any scientific evidence. Every UK care home resident has now been offered their first vaccination, but many have had their second vaccination appointment postponed until further notice – including my elderly mother.

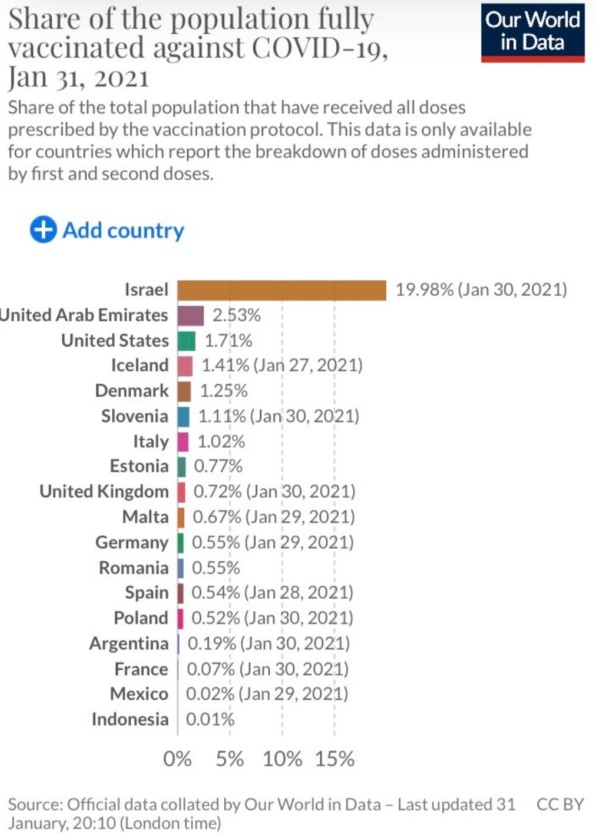

If we consider the picture re first and second doses, on January 30th, the UK had vaccinated 0.72% of the population with their two doses. On January 28th, Spain was close behind, with 0.54% of the population having received a second dose.

The Covid crisis has kept us distant from family, friends, neighbours, and society. At times, it has been a difficult struggle, and not easy to see how, or when, we will return to something close to normality. However, we must not let our isolation make us isolationist.

This is a global crisis. It cannot be resolved by standing alone or arguing with the neighbours about supply issues. Some countries haven’t yet started vaccinating their citizens, such as Nigeria, which has a population of 206,000,000. As seen with the UK’s late and less stringent lockdown, failure to tackle Covid will result in mutations. So far, it seems that the current vaccines can deal with these mutations, but there is no guarantee against future ones.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) warned the UK about delaying second vaccinations in early January. Last week, the WHO urged the UK to pause Covid jabs, once the vulnerable have been immunised, to ensure fair global access to supplies.

The UN secretary general, António Guterres, said that governments have a duty to protect their people, “but ‘vaccinationalism’ is self-defeating and will delay global recovery”. He warned that “science is succeeding, but solidarity is failing. Vaccines are reaching high-income countries quickly, while the world’s poorest have none at all”.

I sincerely hope that, unlike the UK, Spain continues with its current strategy of giving second doses in a timely fashion. I would like to think that, within two or three months of receiving my first dose, I will be fully immune. If that means waiting a little longer, I can live with that. If it means that other, poorer countries have a chance at protecting their citizens, I can live with that too.

If all we care about is ourselves – whether as individuals or as a country – where does that leave us? Health Secretary, Matt Hancock, suggested recently that the UK might be “open” by summer, but only to Brits. Whether that’s a realistic prospect remains to be seen, but is a country really “open” if its borders are closed and people cannot enter or exit?

I want to feel safe again, but not at the expense of my neighbour – whether that’s the family, or the country, next-door. Say no to “vaccinationalism”. The only way for us to be safe from Covid is to make the planet safe from Covid, and we can only do that by working together.

By Sue Wilson – Chair of Bremain in Spain

READ MORE:

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Another completely biased opinion from the arch remoaner,surly you can find someone a little more less biased than Ms Wilson

Regards

Dave Jack