A very Swedish debate has just taken place and is continuing to stir up emotions online, dividing our newspapers' culture and opinion sections. Families and their toboggans (or pulka in Swedish) have apparently been out in droves to slide down the hills of Stockholm's famous Skogskyrkogården cemetery, upsetting mourners and church staff.

Naturally, no one is blaming the kids – children will play anywhere, and nothing can keep a Swedish kid from taking advantage of the first sled-able snow – and if the parents were humbly apologising for their lack of judgment, this wouldn't be a story.

But it's the clueless middle-class mums and dads of Skogskyrkogården who've really set other Swedes off. One dad explains to the SVT television crew, without a hint of irony, that sleighing on graveyards isn't an issue, as long as mourners and screaming kids racing across loved ones' final resting places “respect each other”.

Pulka-gate offers an intriguing starting point to delve deeper into the Swedish character and psyche. Our individualism is, as you may guess from the quote above, at the heart of things.

If you look for Sweden on the World Values Survey map, you'll find us at the most extreme corner, the furthest away from “traditional values” and premiering “self-expression values” – a k a The Great Swedish Project of Self-Realisation – over “survival” more than any other measured country.

Apply this knowledge on mystifying Swedish phenomena, from our Covid-19 strategy to sleighing on the dead, and Sweden will start making sense.

Another key is the radical secularisation process that has taken place over the last century. With large immigration figures in recent years, the picture is more mixed than ever, but the people in charge in Swedish society are still predominantly white and rarely practising Muslims or Orthodox Christians. The church is so weak it's practically invisible, not least in the public debate.

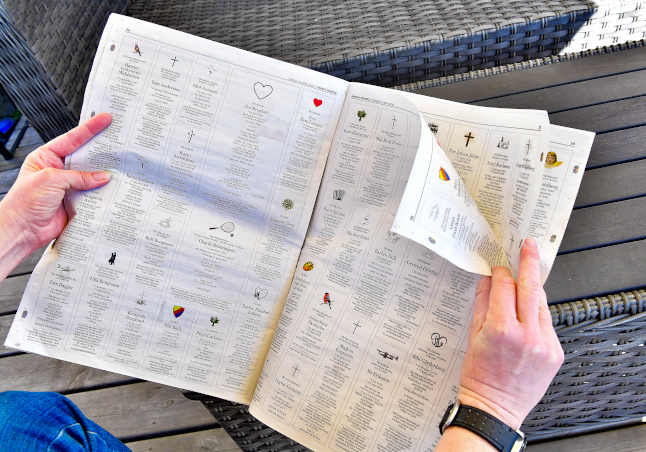

For one, this means we've managed to almost fully erase death from our daily lives (until someone close to us passes, of course). The dwindling number who subscribe to physical newspapers may catch sight of the obituaries while looking for the movie times listings, but that's about it.

Obituaries in Swedish newspaper DN in 2020. Photo: Jonas Ekströmer/TT

On the largest opinion page in Sweden, representatives of the influential secular association Humanisterna recently argued that Sweden must sever its last remaining official ties to the church, however insignificant they may seem. Among other things, putting the church in charge of occasions such as national mourning ceremonies risks offending secular Swedes, who could find it “distasteful” or even “cruelly inconsiderate,” the writers claim.

In the land where individual choices are practically a religion, Humanisterna also lobby for the legalising of euthanasia: “Adversaries often claim that life is a gift from God and holy, but in a secular country, the personal beliefs of some can't be allowed to dictate how others should live and die.”

A fun family outing among mourners on the local cemetery is suddenly not so mystifying, right?

Before you start seeing us as cold, self-obsessed monsters, here's a mundane yet plausible explanation: it's snowing! Adults and children alike lose it completely when the first snow starts to fall. Other countries have also seen instances of people being so overexcited by the snow that they disrespect grave and memorial sites. News media across the world report incidents where German locals are sledding and skiing across graves at, horror of horrors, the memorial site of Buchenwald concentration camp.

You'd think in Sweden we'd be used to the snow, but in the mid to southern parts of the country (including Stockholm), white Christmases are increasingly a thing of the past. Something thaws in our heathen hearts as the ground is reassuringly covered with snow this year, too. But please let's remember that neither excitement over the snow nor secularism should mean disregarding other people's customs – and find another hill to slide down.

Lisa Bjurwald is a Swedish journalist and author covering current affairs, culture and politics since the mid-1990s. Her latest work BB-krisen, on the Swedish maternity care crisis, was dubbed Best reportage book of 2019 by Aftonbladet daily newspaper. She is also an external columnist for The Local – read her columns here.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Your individualism has made you insensitive to being human.

And you are indeed cold and self-obsessed… maybe not monsters, but so far from what can be considered humans.