Italy’s government announced on Monday that it would significantly increase its maximum detention period for migrants, after the Sicilian island of Lampedusa became overwhelmed last week with arrivals from across the Mediterranean.

Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s government says it hopes that raising the limit to 18 months will increase the number of successful repatriations of people whose asylum claims are rejected, and deter traffickers in North Africa.

READ ALSO: Italy to detain migrants for longer as arrival numbers surge

The announcement follows the government’s declaration of a migration ‘state of emergency’ in April in response to soaring numbers of arrivals to Italy via the Central Mediterranean route.

How have the numbers of people arriving in Italy by sea changed in recent years, and where are they coming from? Here are five infographics that shed some light on the situation.

How have arrivals fluctuated since 2015?

The bar chart below visualises the number of migrants who have arrived in Italy each year since 2015, according to data published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and Italy’s interior ministry.

You can see that the numbers of migrants coming to Italy via the Central Mediterranean route peaked in 2016, when the so-called ‘migrant crisis’ was at its height, and fell significantly in 2018-2019, before rising again steadily from 2020.

READ ALSO: What’s behind Italy’s soaring number of migrant arrivals?

Note that the column for 2023 covers only the first eight months of the year up until mid-September.

A combination of factors, including a highly unstable economic and political situation in Tunisia and the surrounding region, are thought to be contributing to the increased numbers of people making the journey in 2023.

Where are people coming from?

The largest group of migrants arriving in Italy by sea so far in 2023 come from Guinea (12 percent), Ivory Coast (11 percent), Tunisia (9 percent), Egypt (6 percent) and Bangladesh (6 percent).

They’re followed by migrants from Burkina Faso and Pakistan (both 5 percent), Syria (4 percent), and Mali and Cameroon (3 percent each), with over one third of arrivals coming from a mix of other countries.

That’s a change from 2022, when according to UNHCR data the largest groups of migrants came from Egypt (20 percent), followed by Tunisia (18 percent), Bangladesh (14 percent), Syria (8 percent), Afghanistan (7 percent), Ivory Coast (5 percent), Guinea (5 percent), Pakistan (3 percent) Iran (2 percent) and Eritrea (2 percent).

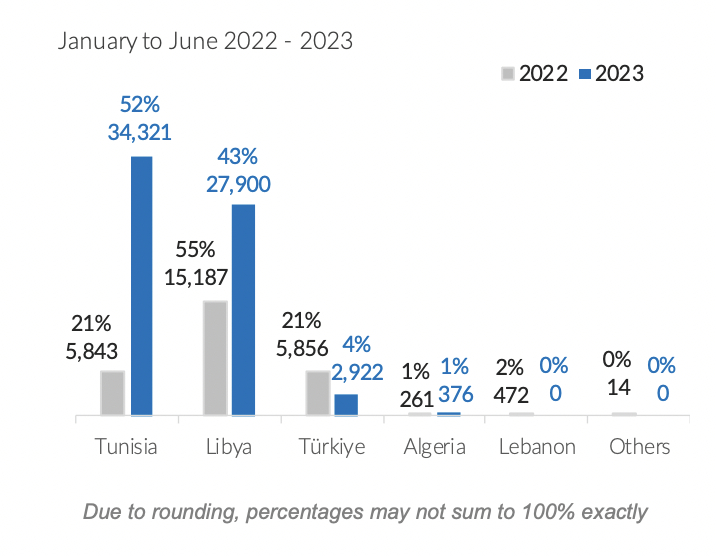

Where are people travelling from?

According to the UNHRC’s most recent Sea Arrivals Dashboard for Italy, 52 percent of people who came to Italy by sea in the first six months of 2023 left from Tunisia, up from just 21 percent in the same period in 2022.

43 percent came from Libya in January-June 2023, compared to 55 percent in the same period in 2022 – showing that Tunisia has clearly surpassed Libya as the main embarkation point for migrants travelling across the Mediterranean to Italy.

That’s partly down to worsening social and economic conditions for both locals and migrants in Tunisia, where President Kais Saied has stirred up race hate against migrants and the economy is flailing.

But International Organization for Migration (IOM) data shows that there is also a rising number of people arriving from Tunisia after crossing from Libya.

Just four percent of migrants arrived from Turkey in the first half of 2023 – a major drop from 21 percent in 2022.

Where in Italy are they arriving?

As you might expect, the UNHCR’s data portal shows that by far the largest proportion of migrants disembarking in Italy land on the island of Sicily.

It’s the tiny Sicilian island of Lampedusa, closest to Tunisia, that has experienced particular overcrowding problems in the past week.

Flavio Di Giacomo, a spokesperson for the IOM in the Mediterranean, told the Italian news site Fanpage that in previous years this issue had been avoided as most people travelled from Libya, and NGO rescue boats would take people to large Sicilian ports.

As more and more people are now arriving in small fishing boats from Tunisia, and Italy’s government has clamped down on the work of rescue organisations, Lampedusa is more exposed to sudden surges it is ill-equipped to handle.

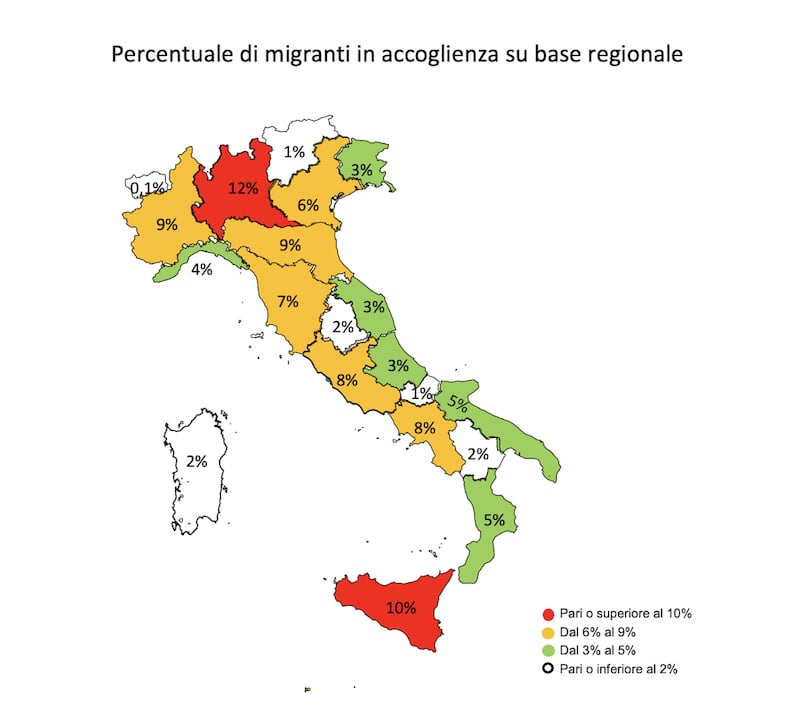

Which Italian regions are hosting the most people?

The northern region of Lombardy, which contains Milan, is the Italian region hosting the highest number of new arrivals (12 percent) in reception and integration centres.

It’s followed by Piedmont and Emilia-Romagna (9 percent each), Lazio and Campania (8 percent each), Tuscany (7 percent) and Veneto (6 percent).

Northwestern Valle d’Aosta, with its population of just over 125,000, hosts just 0.1 percent, while Trentino-Alto Adige and Molise have 1 percent each.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments