Another week, another Corona news story in Germany so absurd that it would be laughable if it weren’t so serious.

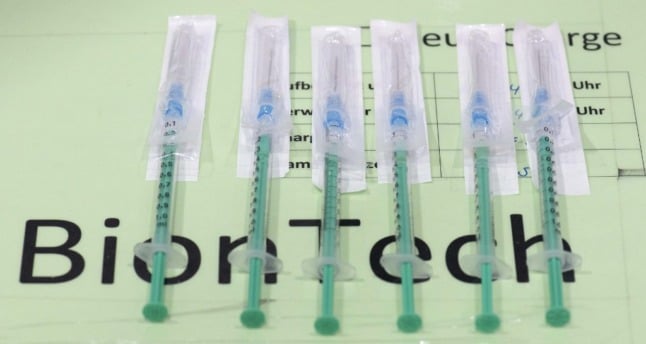

Yes, in a week in which we see exponential growth in Coronavirus case numbers and over 1,000 mainly unvaccinated people are set to die of Covid, our caretaker health minister gets caught up in a controversy about limiting the use of Biontech/Pfizer in order to make a dent in an excess of Moderna stocks.

The fact that Jens Spahn (whatever else you might say about him) is aware that we have a vaccine which needs using up before it expires and is trying to make sure this happens is, I think, a good thing. In other countries, this might have been a positive story – if it were, outside of the trade press or the Twitter Corona bubble, news at all.

Elsewhere in Europe, the average person doesn’t seem particularly interested in precisely which of the several highly-effective vaccines developed with remarkable speed they are offered against a highly dangerous illness. With us Germans, though, it’s more complicated.

If they do want to get vaccinated at all, Germans want it to be with their own success-story, Pfizer-BioNtech – and nothing else, mistaking receipt of a potentially life-saving vaccine just over 18 months into a pandemic for a trip to the car dealership.

This kind of behaviour started early when Germans, having spent three unbearable months at the beginning of the year complaining about vaccine shortages, soon got very picky indeed about which jab they wanted: in April and May, the no-show rate for Astra Zeneca shot up after Germany’s media, with little else to report on during a seven-month shut-down, filled pages and airtime with endless agonising about a minimally higher (yet still infinitesimal) thrombosis risk as compared to Biontech.

OPINION: Covid has sent Germany into hysteria again but the remedy is under its nose

‘Rolls Royce rather than a Mercedes’

Those of us who didn’t grow up in Germany find two things incredible about this. Firstly: people were told prior to attendance which vaccine they were going to get; most Brits I know didn’t even think to ask. Secondly: people didn’t even have the courtesy to call and cancel so that someone else might get a jab.

Instead, they were too busy ringing around to see if they could get their precious Biontech elsewhere. I think it says a lot about the country we’re living in in that several friends of mine openly admitted they wanted Biontech because it had the shortest gap between doses, allowing for fully-vaccinated holidays earlier.

Spahn is aware that we Germans mistakenly see vaccination as a branded experience, but rather than challenge this misunderstanding, he pandered to it in the recent press conference, arguing that, with Moderna, Germans would be getting a “Rolls Royce rather than a Mercedes”. The problem, of course, is that this underestimates the role of our deplorable ‘Made in Germany’ chauvinism. Moreover, unless the health minister actually changes the rules on how vaccination works (and, as caretaker, he now has no mandate to do so), all the arguing in the world cannot prevent Germans from going hunting for Biontech.

That’s because healthcare in Germany is organised around the principle of consumer choice. Not all Germans – and, except for Americans, few foreigners who move here – are fully aware of this fact, or of what it means.

For a start, Germans can choose their doctors (freie Artzwahl), and apart from those in a few specialisms, surgeries can take walk-up business; state health insurance policies will cover treatment.

‘Only America gets considerably less bang for it buck than Germany’

This is in stark contrast to many comparable European countries, where comprehensive health coverage goes hand-in-hand with primary care systems requiring patients to consult GPs before seeking specialist treatment. So while there are general practitioners in Germany (Hausärzte/Allgemeinmediziner), many patients simply don’t have one – especially if they are highly mobile and in good health.

In non-pandemic times, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Until I was in my early 30s, I didn’t have a GP either; if I got an ear infection (I’m a keen swimmer), I’d go straight to the ENT; for rashes, I’d go to the dermatologist. In total, I was probably at a doctor’s surgery around once a year; a GP system would potentially have doubled the number of visits.

There are considerable drawbacks, however. Until the Pandemic, doctors’ surgeries in Germany were full of people who didn’t need to be there: some would mistakenly self-diagnose and go to the wrong specialist, while others were seeking a third, fourth, or even fifth opinion on a minor complaint.

While a GP system without recourse to second opinions can lead to missed diagnoses, Germany has an army of the worried well who, when told by two specialists that it’s nothing to worry about, will simply keep going until they find one who’ll take them seriously – and, of course, earn a pretty penny for consultations reimbursed by state insurance.

This systemic inefficiency is one of the reasons why Germany has some of the developed world’s highest health spending as a percentage of GDP, but life-expectancy which is middling at best. Only America gets considerably less bang for it buck.

‘Germany feels lie living in a loony bin right now’

Another key principle of healthcare in Germany is that, as well as their doctors, Germans get to choose their treatments to a degree unimaginable elsewhere. As such, those who have spent too long consulting Dr. Google will traipse from practice to practice trying to find someone unscrupulous enough to just give them whatever they want regardless of effectiveness; while rules on prescriptions prevent genuine malpractice, the fact that state health insurance reimburses homeopathic treatments (yes, I know…) means that doctors at least have harmless placebos to hand.

Certainly, free choice does mean that some patients with rare diseases who would otherwise slip through the net might have a better chance of finding help (provided they know and understand the system). In this pandemic, though, trying to get a population used to picking and choosing its treatments like yoghurts from a supermarket shelf, to just get the jab is proving problematic at best. Essentially, due to its patient-choice led system, Germany neither has a centralised infrastructure for contacting its population in a vaccination drive nor does its population accept being told when to come to get vaccinated and with what.

In the short term, this dysfunctionality actually worked to my advantage in spring: I got vaccinated far earlier than I would have in the UK because I told my Hamburg GP that I would be willing to take any jab whatsoever at a moment’s notice; she knows that I regularly visit a care home and so prioritised me for one of the many unused AZ jabs that same afternoon.

In the long run, of course, the German approach hasn’t worked out for me at all: I’m living in a country which, heading into a winter of Corona havoc, feels increasingly like a loony-bin.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments