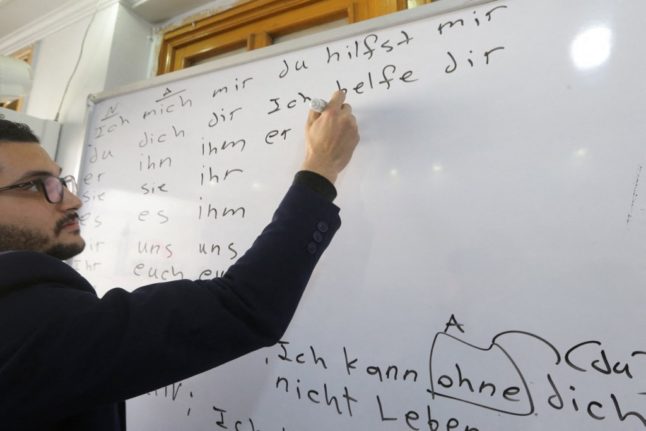

Around 289 million people have learned German as a foreign language

German language skills are an increasingly attractive prospect in many industries.

German is the second most commonly used scientific language, meaning that learning German is an investment for anyone involved in scientific or research ventures.

According to a 2020 survey by the Federal Foreign Office, the Goethe-Institut, Deutsche Welle, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and the Central Agency for Schools Abroad (ZfA), Poland is the country with the most German learners, at almost 2 million. Other countries where German studies are popular include Russia, France, Egypt, Mexico and Kenya.

Countries like Austria, Germany and Switzerland also have a towering reputation for philosophers, poets and playwrights, which may be another reason why language enthusiasts and Germanophiles today are willing to invest their time in becoming proficient.

There are over 130 million people in the world who speak German as their mother tongue or a second language

Not only is German the most widely spoken native language within the EU, it is also the 11th most widely spoken language in the world.

The German diaspora is significant, particularly in the Americas. Americans with Germanic heritage are the largest ethnic population in the United States and account for one third of the population of people with German ancestry across the globe. Meanwhile, eight percent of Argentina’s population claim German ancestry, compared with seven percent of the population of Brazil.

Many of those belonging to these populations speak German.

READ ALSO:

- 11 maps that help you understand Austria today

- Caffeine, war and Freud: A history of Vienna’s iconic coffee houses

The first recorded encounter with the Proto-Germanic language was recorded in the first century BC

The first records of the language were made when the Romans brushed against settlements around the Rhine. There are no written records in Proto-Germanic itself, but some experts believe that it began to develop around 2000 BC around the western areas of the Baltic Sea.

The first comprehensive German dictionary (the Deutsches Wörterbuch) was founded by the Brothers Grimm in 1838

The first scientific and comprehensive dictionary of the German language, written by the Brothers Grimm, was oriented around exploring the etymology and history of every recorded word used in German. It focused particularly on German literary language from the time of Martin Luther through to Goethe, who had died in 1832.

The publication of the Deutsches Wörterbuch was a huge moment in the history of the German language. Its first shipments sold 10,000 copies. Its influence was hugely wide-ranging and the project was continued by other academics and philologists following the deaths of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm.

Despite its importance in the development of the German language, the dictionary was almost never written. The brothers initially refused to write the text when first approached by a major publishing house in 1830, but after they were made political refugees for refusing to pledge an oath of allegiance to the King of Hanover, Ernst August, they decided to undertake the project as it offered them the opportunity to flee to Berlin.

German used to have its own unique script

Early German printing shows the letterings known as Schwabacher and Textualis as the primary typefaces in documentation, but they were superseded for many centuries by the Fraktur typeface, which was commissioned by Emperor Maximilian I in the 16th century.

The Fraktur typeface is a calligraphic typeface of the Latin alphabet which was used for woodcuts and, in later years, printed books. It is still referred to in German as the ‘deutsche Schrift’ (German script).

While it was initially popular across Europe, Fraktur began to be replaced by Antiqua from the late 18th to late 19th centuries, but remained Germany’s favourite script until it was outlawed by the Nazi Party in 1941.

READ ALSO: The 10 biggest culture shocks experienced by foreigners in Austria

Konrad Duden published the first edition of the Duden dictionary in 1880

This was a turning point in the history of the German language. The first edition of the Complete Orthographic Dictionary of the German Language was published in 1880, and it laid out the spelling rules for the German language until the spelling reforms of the late 1990s.

The ‘Reform Duden’ is the version of the Duden which is updated in line with the rules of the German orthography reform of 1996.

The orthography reform of 1996 was intended to finalise debates about German spelling and punctuation

The spelling reform, which was negotiated by Austria, Germany, Liechtenstein and Switzerland, intended to finalise changes to German orthography in order to simplify it and make it more consistent.

It focused on rules for spelling loan words, capitalisation, hyphenated spellings, consistent punctuation and compound words, and followed longstanding pressure to modernise the spelling rules set out by Duden over 100 years before. The rules quickly became obligatory in schools and official administration, but not without widespread debate and opposition from media organisations.

In 2006, the reform had to be edited to reduce its most controversial changes after its remit had already been limited by the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany in 1998, which stated that people could spell as they liked outside of schools due to the lack of legal imperative governing orthography.

It is thought to take 750 hours of study to become proficient in German for native English speakers

The Foreign Service Institute once divided the ‘diplomatically important’ languages of the world into categories based on their difficulty for English speakers.

It moves from Category I languages like French and Spanish, which are supposedly learnable in just 575 hours of study, to Category V languages such as Mandarin, Cantonese, Japanese and Arabic, which can demand up to 2,200 hours of study.

German falls in Category II, hilariously being the only language at all to fall in this category, at 750 hours of learning time. Guess it’s just in a league of its own.

However, some have debunked this strategy of dividing language difficulties. A more productive way of looking at it is the fact that it takes the average German learner of any native tongue around 150-200 hours to progress up each CEFR level (A1 to A2, B1 to B2, etc).

The pandemic spawned more than 1,200 new German words

Apparently, German speakers respond to a stressful situation by making up as many complicated compound nouns as possible to torture those of us who are still learning the language – but that’s all to be expected from the language that coined the term ‘Schadenfreude.’

Since the start of the pandemic, 1200 new German words have been recorded by the Leibniz Institute for the German Language. These range from ‘Abstandsbier’ (a socially-distanced beer with friends) to ‘CoronaFußgruß’ (greeting someone with your foot) and ‘Impfneid’ (envy of those who have already had the vaccine).

READ ALSO:

- The 14 German words that have entered the lexicon in Austria due to the pandemic

- REVEALED: The German versions of famous English sayings

German tongue twisters are the best tongue twisters

Since Germany is such a complex language filled with long, sprawling compound nouns, homonyms, homographs and difficult pronunciation, its tongue twisters (or ‘Zugenbrecher’ in German) are really on another level.

Seriously. Try out these:

Fischers Fritze fischt frische Fische; Frische Fische fischt Fischers Fritze.

This translates as ‘Fritz, the son of the fisherman, fishes for fresh fish; for fresh fish fishes Fritz, the son of the fisherman’.

Am Zehnten Zehnten um zehn Uhr zehn zogen zehn zahme Ziegen zehn Zentner Zucker zum Zoo.

This translates as ‘on the tenth of October at ten past ten, ten tame goats pull ten centners of sugar to the zoo.’

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments