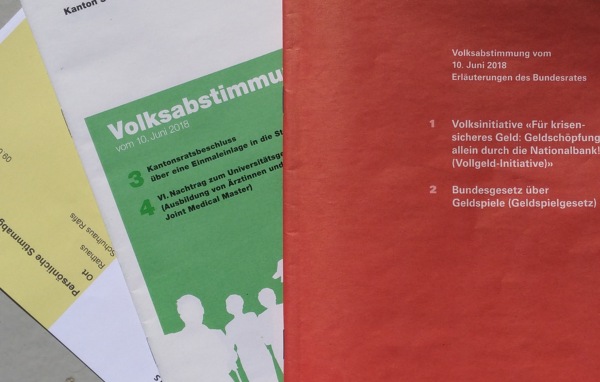

Around four times a year, households all over Switzerland received bulky envelopes stuffed with ballot papers and information about the country’s upcoming referendum.

This is a regular occurrence in Switzerland where direct democracy is a key feature of the political landscape.

In addition to frequent referenda, some cantons hold open air discussions on particular issues, known as Landsgemeinde.

But how does the process work? Who can vote? And how are the issues to be voted on chosen?

Here we take a look at the key features of the Swiss system where supreme sovereignty resides with the people.

How often do referendums take place?

Swiss people vote in referendums up to four times a year. They vote on around 15 federal proposals and also cast their ballot on issues affecting individual cantons at the same time.

Who can vote?

All Swiss citizens aged 18 or over can vote, including Swiss citizens registered as living abroad. Around 5.3 million voters are eligible to take part in referendums. That is a little under two thirds of all people living in Switzerland.

However, with nearly one in four (24.6 percent) of people living in Switzerland are not Swiss citizens, Swiss direct democracy has demographic limitations.

How do people vote?

There are three ways to cast a vote: by postal voting (the most popular option), at the ballot box, and, in some cantons, electronically (e-voting). However, e-voting remains controversial with concerns over system security.

Read also: Ten things you need to know about the Swiss political system

In the case of postal voting, envelopes are sent out to people’s homes around two months before the referendum and contain the ballot papers as well as booklets with all the relevant legislation (or proposed legislation), and an outline on arguments in favour and against each proposal. These booklets also contain recommendations from the federal government on whether voters should accept or reject proposals.

What is voter turnout like?

In 2017, Swiss voters were called to vote in referendums on three occasions. The average overall turnout out was around 45 percent. Over the last decade, the figure has been above 40 percent.

Individual issues can attract greater turnout, however. Nearly 55 percent of voters took part in a March referendum calling for compulsory television licenses to be scrapped, with the majority rejecting the move that would have cut funds to the national broadcaster.

Longer-term studies from the Swiss Electoral Study Selects project show that over 90 percent of voters had cast their ballot at least once in the previous 20 votes.

Many people pick and choose when they will vote in referendums depending on their level of interest in a particular issue or how relevant they think it is to them personally.

How do referendum issues get selected?

The Swiss system of direct democracy requires any amendment to the constitution to be put before the people in a referendum.

There are three types of referendum: mandatory referendums, optional referendums and popular initiatives.

Mandatory referendums: All constitutional amendments approved by the federal parliament must be voted on in a mandatory referendum via a popular vote. The electorate must also emergency laws with a validity of longer than one year and Swiss membership of specific international organisations.

For example, in 2001, 76.8 percent of voters rejected a proposal that would have seen Switzerland join the European Union. On the other hand, in 2002, Swiss voters finally decided to join the United Nations with 58.4 percent of people backing the proposal.

For mandatory referendums, a double majority is required: that is, a majority of voters and a majority of cantons must vote in favour of the proposal.

.jpg)

A sample signature collection forum for an optional referendum.

Optional referendums: Any 50,000 Swiss citizens (or eight cantons) may request an optional referendum to contest a new or revised law. In the case of individual citizens, they must gather 50,000 signatures within 100 days. If the referendum goes ahead, the new law is passed or rejected by a simple majority of voters.

Popular initiatives: Since 1891 citizens may also demand a change to the constitution via referendum by launching a popular initiative. It must be launched by a group of at least seven citizens and must then be backed by 100,000 signatures within 18 months to push it to a referendum. A double majority of the people and the cantons is required for it to pass.

These popular initiatives often make the biggest headlines overseas: in 2016, for example, a popular initiative to introduce a universal basic income made it to the polls but only 23.1 percent of people voted in favour.

The federal government can also reject popular initiatives in part or in full under certain conditions, and may also put forward counter proposals.

How many referendums are successfully passed?

The Swiss have been called on to vote around 306 times since 1848 for a total of 617 proposals. In total, 299 proposals have been passed while 334 have been rejected. The numbers don’t match up exactly because single initiatives can sometimes include both a proposal and a counter-proposal.

When it comes to popular initiatives, however, the story is quite different. From 1891 to 2016 some 209 popular initiatives were voted on but only 22 were accepted.

Examples of popular initiatives that have somewhat controversially succeeded include the 2009 initiative to ban minarets, which was described as unconstitutional by the Swiss government, and the 2014 anti-mass immigration initiative.

But it should be noted that in cases where popular initiatives fail, they still play an important role in stimulating political debate and create a level of engagement in – and knowledge about –political issues that can be surprising to people from countries where voting is something you do every four years or so.

Another advantage of these popular initiatives is that Swiss political parties must seek consensus not just across party lines, but also in the broader community as new laws can be challenged by the people.

When is the next vote?

The votes take place four times a year. To find out more about the upcoming vote, please check out the following link.

In a classic example of Swiss planning, the dates for upcoming referendums have been set all the way to 2034, although the actual proposals to be voted on have yet to be established.

What is the Landsgemeinde?

In Glarus and Appenzell Innerhoden, voters practice a rare form of democratic engagement called the Landsgemeinde or ‘open-air assembly’ which dates back 600 years.

Every year, voters from across the northeastern demi-canton, or region, of Appenzell Innerhoden flood into the Landsgemeindeplatz to elect their local leaders and judges — not by casting ballots but by raising their hands.

The tradition of the Landsgemeinde, or open-air assembly, dates back to the 14th century, and in Appenzell is held every year on the last Sunday in April.

‘Pure democracy’: What is Switzerland’s Landsgemeinde (open-air assembly)?

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.