Just as soon as you think you’ve mastered the German language, you may feel that confidence completely shattered after finding that there can be dozens of different words for one thing, depending on where you go in the country.

Regional dialects and culinary traditions can complicate the matter because everyone seems to stick to their own terms for slippers, or for what to call their particular “local cuisine” – even if it's essentially the same recipe as in the state next door.

Ordering a Pfannkuchen in Berlin might get you your jelly-filled donut, but doing the same in most other places will get you a pancake. And while folks in the southwest might present you with a Weckmann (gingerbread man) around Christmastime, most in the East will just be left scratching their heads about what you want.

Here are a look at some of the concepts that the German language could perhaps consolidate a bit, based on research by Spiegel Online, Tages-Anzeiger and the app “Dialäkt Äpp”.

1. There are at least 25 different words for hiccup

Photo: DPA.

Photo: DPA.

What’s the German word for hiccup? That depends on who you ask and where. You might hear the more standard Hochdeutsch (high German) term Schluckauf.

Or Hädscher is you’re in the region of Franconia in central to southern Germany. And venture even further south to hear Hecker, Schnackler or even Schnackerl in Austria.

And of course the Swiss have to put their cutesy -i ending on their term: Hitzgi.

2. There are 12 different words for a pancake

Photo: DPA.

Photo: DPA.

And it’s not just Berlin that has its own name for the fairly standard breakfast fare.

Das Omlett or die Omelette is preferred in the west, particularly near the borders with France, or around German-speaking parts of Switzerland.

And then there’s Plinse or Plinz, which is heard near Leipzig or along the Polish border, which is basically a pancake, though English speakers might call them blintzes.

And in and around Austria, you might hear the term Palatschinke, or Palatschinken.

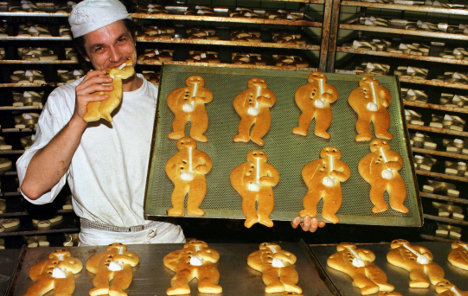

3. There are 12 words for a gingerbread man

Photo: DPA.

Photo: DPA.

We dare you to find another English term for gingerbread man, but in the German-speaking world, it might actually be hard to agree on just one.

The term Lebkuchenmann is almost never spoken in the far western part of the country, according to Spiegel, but it seems to be the standard in cities like Munich, Berlin and Hanover.

Weckmann or Weckmännchen is far more preferred in the Rhineland and southwest, while Stutenkerl (literally fruit loaf fellow) is preferred in the northwest. But the difference in regional recipes might be part of why there are various names: Lebkuchen is a spiced dough, more similar to gingerbread, while Stuten often has raisins.

Meanwhile the man-shaped festive treat enjoyed near and within Austria is named after the region’s sinister demon creature who punishes bad children at Christmas time: Krampus.

And the area around Stuttgart and Karlsruhe seems to have its own unique name for such a dessert: Dambedei.

4. 15 words for basically a meatball

Photo: DPA.

Photo: DPA.

If you’ve had any sampling of German cuisine, you know a lot of it has to do with ground meat, whether in a sausage or other form.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that there is regional debate about what to call what is essentially a meatball.

Frikadelle, if you live in the central west to northwest, but Fleischküchle if in the southwest. Klops or Kloss in certain parts of the east, especially around Leipzig. But Beefsteak is even quite common for both Leipzig and Dresden.

And Fleischplanzl or Fleischpflanzerl if in Bavaria, especially Munich.

5. Nine different words for making small talk

Photo: DPA.

Photo: DPA.

There are certainly a number of colloquial phrases for having a casual chat in English – shooting the breeze in the US or blethering in the UK. But Germans seem to really like thinking up words for this daily ritual.

Quatschen is a favourite in both east and west, though not so much right in the middle. Ratschen is much more common in the south, while the north and northwest seem to like klönen.

Schnacken is also a fun one from the north, around Hamburg. And babbeln is a good one to throw out there when in Hesse or Baden-Württemberg.

6. 'Slippers' come in ten varieties

Photo: DPA.

Photo: DPA.

You might call your cozy, well-worn slippers Pantoffeln, but not many folks in Berlin or Hanover would agree with this vocabulary.

You could call them the almost Dr Seuss-sounding Schluffen, but that’s really only used in the western Rhineland, and perhaps in Frankfurt.

Just referring to them as Hausschuhe will probably get you the farthest no matter where you are in the country. But you might also be tempted to use this fun-to-say eastern word: Bambuschen.

7. 11 ways to talk about a slingshot

Ok really Germany, how many words do you need for slingshot? Apparently at least 11: Schleuder, Zwille, Fletsche, Flitsche, Katsche and more.

Are all of them really necessary?

8. 14 ways to mash potatoes

Part of the great variety on this one is that southern Germans often say Erdapfel (literally earth apple) instead of Kartoffel. And on top of that you can add the ending of -brei, -püree or stock, depending on where you live.

But then there are those who live in the historical region of Upper Lusatia in the east near Poland and the Czech Republic who have their own word for the dish: Mauke.

9. More than 50 words for the end piece of bread

We wonder which of the 50 words he's sniffing out from this end of bread. Photo: DPA.

We at The Local struggled to find just one English word to define the end piece of a loaf of bread. But perhaps we should steal one from Germans, because they have at least 51 different ways to describe this concept.

For all The Local's guides to learning German CLICK HERE

Which one’s your favourite? Take your pick:

-

Kanten – throughout Germany

-

Kante – mostly Germany

-

Anschnitt – mostly Baden-Württemberg

-

Anhau – parts of Switzerland

-

Kipf – mostly southern Germany, around Munich

-

Kipfel – mostly southern Germany and Hesse

-

Ranft – southern, central and eastern Germany

-

Ränftchen – centre and east Germany

-

Raftl – not so common: parts southern Germany and Austria

-

Rankl – mostly Bavaria

-

Rämpftla – Bavaria and Saxony

-

Knorze – Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate

-

Knorzen – Frankfurt

-

Knust – throughout Germany

-

Knüstchen – mostly central west Germany

-

Knietzchen – the very centre of Germany

-

Kniesje – near the border with France

-

Knäuschen – mostly west and southwest

-

Knäusle – mostly Baden-Württemberg

-

Knerzel – Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate

-

Knetzla – Mostly Cologne and Nurenberg

-

Knerzje – Rhineland-Palatinate

-

Scherz – parts of Bavaria and Austria

-

Scherzel – parts of Bavaria and Austria

-

Scherzerl – parts of Bavaria and Austria

-

Zipfel – Vienna, parts of Switzerland and southern Germany

-

Kruste – mostly western germany and Frankfurt

-

Krust – Cochem, Rhineland Palatinate

-

Krüstchen – mostly western Germany

-

Kirschte – parts of west Germany

-

Kierschtsche – parts of west Germany

-

Korscht – parts of west Germany

-

Kuuscht – parts of west Germany

-

Kürstchen – parts of west Germany

-

Knäppke – west and northwest Germany

-

Knippchen – parts of west Germany

-

Mürggu – Switzerland

-

Mirggel – parts of Switzerland

-

Muger – parts of Switzerland

-

Mutsch – parts of Switzerland

-

Küppla – parts of northern Bavaria

-

Küpple – central Germany

-

Köppla – parts of northern Bavaria

-

Kübbele – central Germany

-

Reifle – parts of southern Germany

-

Riebele – mostly Baden-Württemberg, but also Bonn and Hamburg

-

Rindl – parts of Bavaria and east Germany

-

Chäppeli – Switzerland

-

Chäppi – Switzerland

-

Houdi -Switzerland

- Das Ende – various parts of Germany

.jpg)

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

The end of a loaf of sliced Bread I always knew as The Crust in Derbyshire.Unsliced? Hmmm..

It’s no use posting the nouns without the articles ….. 🙂

In Scotland we call the end of a loaf of bread the heel.