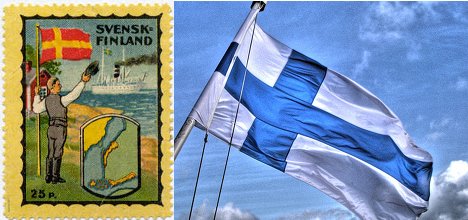

They have been called the world’s most pampered minority and it is easy to see why. Despite comprising just 5.5 percent of the population, Swedish-speaking Finns have their own newspapers, broadcasts and road signs, and all government documents and websites are translated into Swedish. However, there are those who fear that the special status of the language could soon be threatened.

The language is a reminder of the close historical ties between Sweden and Finland. They were one country for four centuries, but parted ways 201 years ago. The language was a legacy that survived over a century of Russian rule.

The language is now spoken by about 275,000 people in mainland Finland, plus some 25,000 in Åland, an autonomous archipelago in the Gulf of Bothnia between Finland and Sweden.

The past century has seen Swedish-speaking Finns in almost constant decline. In 1900, Swedish speakers made up about 13 percent of the population. Finnish nationalism in the late 19th century, plus emigration to Sweden during the Second World War, have led to their numbers dwindling.

Despite this numerical decline, Swedish speakers maintain a firm grip on the country’s constitution. They have their own political party in government, the Swedish People’s Party of Finland (Svenska Folkpartiet i Finland) and a vast number of cultural institutions. The Swedish Assembly of Finland, Folktinget, is their own cross-political body that protects the interest of the Swedish speaking Finns and acts as a forum for political discussion and cooperation.

The Assembly participates in Finland’s law-drafting process and all political parties with activities in Swedish are members. Swedish speakers have their own schools, health and day care centres, theatres, newspapers and broadcasts in Swedish. Swedish speakers have a legal right to be served in Swedish when dealing with state authorities.

Swedish-speaker Erika Helling, 43, teaches at the secondary school Högstadium in Sibbo, a bilingual municipality east of Helsinki. She says that she always speaks Swedish in Sibbo whether she goes to the bank, supermarket or health care centre.

“Everybody that works in Sibbo is or bilingual or at least functional in both languages,” she said. “It is practically impossible to get a job in Sibbo if you don’t speak both languages.”

The Swedish-speaking minority comprises about 40 percent of Sibbo’s population. In almost all cities and towns in Finland, public signs such as street names or traffic signs are in both Finnish and Swedish, with the majority language always first. However, in some unilingual municipalities, it is common to see just one of the languages.

Unlike in English, where both language groups are referred to as Finns, Swedish speakers use the Swedish word finländare (“Finlander”) when referring to both Finnish- and Swedish-speaking nationals. The word “finne” (“Finn”) is reserved for a Finnish-speaking Finn.

Both Swedish and Finnish are compulsory subjects at school for both Swedish and Finnish speakers, with pupils almost always receiving instruction in their native language. Tuition in the other language forms part of the curriculum in secondary school and upper secondary school. Students at universities and polytechnics are required to take an examination in the other domestic language. At the university level, there is a system of quotas and affirmative action for Swedish speakers. A certain percentage of students applying for the universities must be Swedophones.

Yet there are signs that the demographic reality could now be catching up with Finland’s Swedish speakers. There is growing resistance to learning Swedish among Finnish-speaking students. They claim that Swedish is of limited use to them in the jobs market and that other languages are more important in a globalised economy.

Others say that allowing Finns to drop Swedish will eventually lead to the death of the language in Finland and threaten the liability of the Swedish-speaking minority linguistic minority. If Swedish dies out, the argument goes, Finland will have lost an important part of its heritage.

There are also those that argue that making Swedish compulsory just puts pupils off, but this is not an argument that finds much favour with Erika Helling, who teaches literature and Swedish as a mother tongue to youngsters between the ages of 13 and 16.

“Of course everyone is more more positive if they aren’t forced to learn a subject,” she argued. “But I don’t think that this should be a guideline for anything. Knowing Swedish eventually results in more Finns knowing a Germanic language. This makes it easier to learn other languages of this linguistic group, such as English and German.”

The debate about Swedish is not just about language. The class and power of Swedish speakers have arguably strengthened the language’s status in the past, but also adds to the ammunition of those now calling for its role to be reduced.

Swedish speakers are often criticised for isolating themselves as an elite group. Many of the wealthy and powerful families of Finland are Swedish speakers. They are often accused of being the world’s most pampered minority, given their relatively tiny numbers and the huge concessions made to their language. But for Helling, the protection of the language is not pampering, but a sign that “Finland is giving a good example of how minorities should be treated and protected all over the world.”

“Minorities should have rights like everybody else,” she said. “Otherwise all ethnicities will die of extinction. I think Finland should be an example for other countries. Though a lot still has to be done.”

Finland has already started chipping away at Swedish’s special status. In 2005, despite fierce lobbying from powerful Swedish speakers, the government eliminated Swedish from the tough final matriculation exam, which enables students to apply for universities.

Yet amid the setbacks, there are signs that Swedish might be making a comeback. In these last years the decline in the proportion of Swedish speakers has stopped. There are also signs of renewed interest from parents in Swedish-language schooling, something Helling welcomes.

“The trend in the past few years is that children coming from bilingual families very often attend Swedish schools,” she said. “I believe there is a change in attitude indicating a more positive approach. Yes, there definitely is hope.”

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments