If you come from a country with a more dynamic and pro-active way of doing things, then you may grow frustrated with Switzerland’s careful and measured approach to implementing change.

Part of the reason for this sluggishness is cultural: the Swiss don’t like spontaneity (unless it’s planned) or doing anything on a whim.

They believe that rushing things and making hasty decisions will have disastrous results, which is why they prefer to take a cautious — even if painstakingly slow — path.

As a general rule, the Swiss have a penchant not only for planning, but for pre-planning as well. They like to thoroughly examine each aspect of a proposed change and look at it from all possible angles.

For instance, before any major decision is made, especially one involving the use of public funds, commissions are formed to look into the feasibility of a given project. That in itself could take a while.

Sometimes, a smaller commission is created to assess the need for a bigger commission to be formed.

Whether at a federal, cantonal, or municipal level, the country is teeming with various commissions, committees, panels, and task forces, each taking its time to come up with proposals / decisions / solutions.

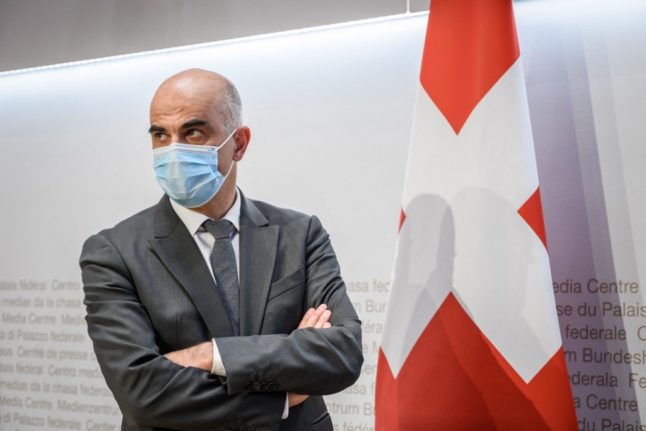

Even during the Covid pandemic, when quick decisions were literally a matter of life and death, Switzerland trailed behind other countries in implementing various rules, while the Federal Council carefully considered the validity (or lack thereof) of each measure.

As The Local reported at the time, “while Austria, Germany and other countries in Europe have taken proactive measures weeks ago to rein in the spread of coronavirus, Switzerland has been dragging its feet in mandating tighter rules”.

Newspaper Blick wrote of this time: “A strange serenity reigns in the political world.”

READ MORE: OPINION: Why has Switzerland been so slow in introducing new Covid measures?

The waiting game

Another reason (besides the cultural one mentioned above) contributes to Switzerland’s notorious slowness in decision-making – the country’s political system.

For instance, due to Switzerland’s decentralised form of government, the Federal Council must consult with cantons before a decision can be made at the national level.

That, as you can imagine, could take a while as each of the 26 cantons may drag their individual feet, and there could be no consensus among them.

And then there is Switzerland’s unique brand of direct democracy.

It is fair to say that this system is a double-edged sword: on one hand, it gives the people the power to make decisions that shape their lives, but on the other, it causes all kinds of delays in getting the law off the ground.

That’s because all legislation and constitutional amendments approved by the parliament must be accepted by the voters in a referendum before being enforced.

In a truly Swiss manner, the referendum dates are planned years in advance.

READ MORE: Why has Switzerland set dates for referendums up to the year 2042?

Even after the law is approved, it usually takes at least two years until it actually goes into effect.

All this can help to explain why change is slow to take hold in Switzerland, so you may as well get used to it…and get used to waiting.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments