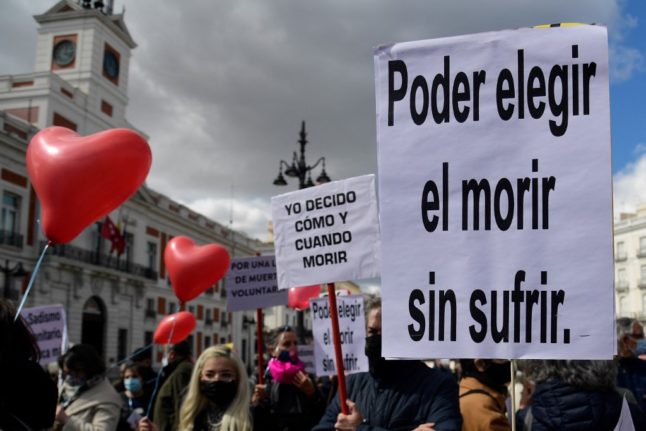

Spain’s historic euthanasia law was passed a year ago on June 25th, 2021.

Since that day at least 171 people have ended their lives through the assisted dying procedure, although the statistics to date are both regional and provisional. That number could, in reality, be higher.

The figure is based on figures from Spanish newspaper El Mundo, although it must be said that it doesn’t include the regions of Asturias and La Rioja, where the data is not yet available.

Before the landmark legislation, assisting somebody who wanted to die was punishable by up to ten years in prison, and the law, which made Spain the fourth country in Europe to allow people to end their own life, following the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, was as controversial as it was groundbreaking.

Pedro Sánchez’s PSOE-led coalition government had to rely on the congressional support of minor left-wing parties to pass the bill, and although it was celebrated by right-to-die campaigners in Spanish society -described as creating a “a more humane and fair society,” by Health Minister Carolina Darias – it outraged many conservative and religious groups.

Although widely known as Spain’s euthanasia law, in reality the legislation prescribes two forms of dying: euthanasia and assisted suicide.

Euthanasia is the procedure of prematurely ending a life to relieve suffering or pain – via lethal injection administered by a doctor, for example.

Assisted suicide, however, is undertaken by the person themselves with help.

Both euthanasia and assisted suicide can be carried out on consenting patients suffering from chronic and debilitating conditions, incurable illness, or conditions that cause immense suffering.

You must be an adult Spanish national or have legal residency in Spain, and be “fully aware and conscious” when you make the request, which must submitted twice in writing, two weeks apart.

But that doesn’t mean that applying, or having your application accepted, is easy.

The Local had delved into the realities of Spain’s historic euthanasia legislation one year on.

Regional variations

Although there are still no officially collected and aggregated statistics on a national level, and even some slight variation on the figures within Spanish media outlets, using provisional regional data it is possible to gage how the law has been implemented in its first year.

Nationally speaking, it seems at least 336 Spaniards requested euthanasia procedures in the first year of legal euthanasia, of which 171 were performed, 18 applications rejected, and 43 still pending decisions.

But data from the first year of euthanasia procedures paints an interesting regional picture. Euthanasia and assisted dying have so far been, it seems, concentrated in certain regions of Spain.

Catalonia, for example, has performed 60 in the first year alone, while Andalusia, with one million more inhabitants than Catalonia, just 11.

In Andalusia, just 19 applications were made, of which 11 were accepted, six rejected and two still pending. In Catalonia that figure was 137.

After Catalonia, Basque Country had the second most euthanasia procedures, with 25 of 75 applications accepted. Third was Madrid, with 19, and fourth the Valencian Community, where 13 procedures have already been completed out of 23 applications made.

On the Balearic Islands, eight were carried out of the 17 applications, whereas in the Canary Islands seven applications were made with four still awaiting a decision.

In Castilla-La Mancha eight applied, with four approved. But in Galicia, it seems the Galician government have a lower threshold for accepting euthanasia applications: of the 19 applications it received this year, just four were accepted.

Similarly, in Castile y Leon, just two of the seven applications were accepted, and it is believed that the process became so drawn out that some patients even died before receiving a verdict.

In Murcia, on the other hand, four of the five total applications have already been carried out. In Cantabria, 12 procedures were requested, five completed, two rejected, and one still pending decision,

Across the rest of Spain’s autonomous communities, none have completed more than five procedures.

How quickly is euthanasia approved in Spain?

Judging from the raw numbers, it seems that Catalonia and the Basque Country are the most willing to grant euthanasia procedures, but are also the fastest bureaucratically speaking: it takes patients, on average, 41 days from application to procedure in the two northern regions.

In Andalusia and Madrid, however, the process is much slower. In Andalusia, for example, the regional government took five months to even implement the law, and it is believed that they have kept applications waiting as long as three months due to a convoluted bureaucratic process that passes the application between different doctors with no streamlined system, which leads to a lag in processing.

Other regions, however, have already set up systems to deal with the applications.

In Catalonia, Navarre, the Basque Country and the Canary Islands, applications are dealt with by specially created teams made up of at least one doctor and a nurse who have studied and specialise in the implementation of the law.

Medical objections

While the issue of euthanasia has long been politically and religiously controversial, the law has also divided doctors. In just the six regions alone where data is available, it is believed 4,500 doctors have objected to the procedures, either refusing to carry it out or withdrawing from the process altogether.

Madrid has had the most objections from doctors, with almost 3,000 in the first year alone, while in Andalusia over 500 have objected.

Interestingly, even in a region with very few applications such as Castille y León, where only seven patients requested the procedure, over 400 doctors have ruled themselves out of the euthanasia process. That is more than Catalonia (167) where the most applications and procedures were recorded.

However many believe, the figures, admittedly provisional and very patchy at a national level, for now, could be hiding greater numbers of doctors who are uncomfortable with Spain’s new euthanasia law.

The president of the Ethics Commission of the Andalusian Council of Medical Associations, Dr. Ángel Hernández Gil, said that “there are a very large number of doctors who are conscientious objectors” but are not recorded in the official statistics “because they are only registering as conscientious objectors when the request arrives. In the event that the application does not arrive, people will not register,” he explained in the Spanish press this week.

Speaking as a representative of the medical profession in Spain’s most populous region, Hernández Gil suggested so many doctors are against euthanasia because they believe “is not within the purpose of medicine.”

“Our position has nothing to do with any kind of political ideology, religious principle or moral principles,” he added.

“We understand that euthanasia is not a medical act.”

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments