We’re living through a time in history where the emergence and resurgence of viruses is becoming more prevalent, from the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic to the appearance of monkeypox, with several cases recently recorded in Spain, Portugal and the UK.

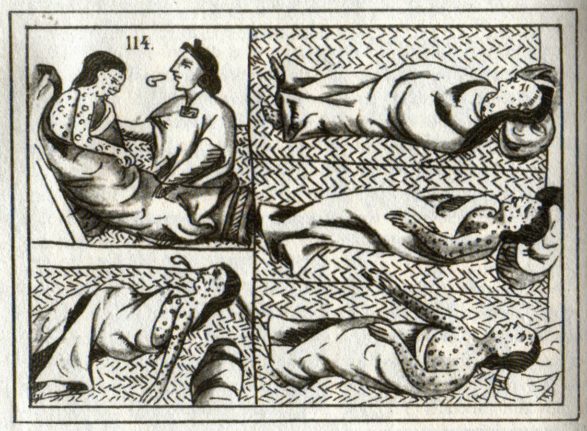

Monkeypox is a similar virus to smallpox, a devastating illness that was finally eradicated in 1980. The virus causes high fever, body aches, headaches and chills, as well as a rash of boils or sores.

READ ALSO: Eight suspected monkeypox cases detected in Spain

While historians and scientists believe that smallpox has been around for the last 3,000 years, monkeypox was first discovered in 1958 when two outbreaks occurred in a group of monkeys kept for research. The first human case of monkeypox was recorded in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The first vaccine

During the 18th century, smallpox was rife throughout the world and was killing millions. It was around this time that English doctor Edward Jenner saw that people who caught the milder bovine virus of cowpox never actually caught the deadlier smallpox.

So in 1796, he took the pus from a cowpox lesion on a milkmaid’s hand and inoculated an eight-year-old boy named James Phipps, rendering him immune to smallpox and creating the world’s first vaccine.

But it was in fact Spain that played a pivotal role in getting this vaccine out to the masses and helping to bring the smallpox virus under control.

How did they transport vaccines in the 18th and 19th century?

Even today, transporting vaccines proves to be problematic, best evidenced by the specific temperature and storage requirements of some of the Covid-19 vaccines, as well the logistical delays and other distribution obstacles.

But back in the early 19th century, doctors and scientists came up against even more problems.

Health professionals at the time invented an ingenious method of taking the puss-like fluid from the sores of those with cowpox and placing it on a piece of material to dry out.

They would then travel to the next town and mix the dried puss with water, before scratching it into people’s skin to infect them with cowpox, thus protecting them from smallpox.

This method seemed to work in Europe, where distances between towns were relatively close.

However, the vaccine wouldn’t stay fresh long enough to take it further across the seas to the Americas. It wouldn’t even work for distances from one European capital to the next, only from town to town.

Children become the vaccine carriers

This is where Spain comes in. The colonial power was desperate to send the vaccine over to its South American territories, where the virus was running rampant throughout the population, killing around half of those it infected.

In 1803, a doctor from Alicante in eastern Spain, Francisco Javier de Balmis, came up with a plan and asked Spain’s King Carlos IV, whose own daughter had died of smallpox, to fund a new mission.

His plan was to sail to the Americas with 22 Spanish orphans on board, infecting them with cowpox along the way, a plan that wouldn’t have much chance of being approved in this day and age due to human rights laws, but this was the early 18th century.

The cowpox vaccine only survived in the body for up to 12 days, so at the beginning of the journey only two of the orphans were infected with smallpox. Then, ten days later when they were sick enough and had boils all over their skin, doctors on board would lance these sores and infect two more boys. The aim was to keep this going every ten days until they reached South America.

Miraculously, the plan of using the orphans as vessels for the virus worked, and although all the children got sick, none of them died.

By the time the ship docked in Venezuela in March 1804, one boy still had fresh sores and puss which could be used to vaccinate the local population.

Balmis and his team set about vaccinating the locals straight away and then split up, with half the team travelling through what is today Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia and the other half up to Mexico.

Amazingly, using this method of lancing boils and moving from town to town, they managed to vaccinate around 200,000 people, most of whom were children.

Locals who received news of their arrival would greet the heroes with all the flamboyance of a Spanish fiesta – complete with music, bullfights and fireworks.

The mission was not yet complete

Balmis left the 22 original orphans with adoptive families in Mexico and then set out on a new voyage with a brand new set of children for the Spanish colony of the Philippines.

The ship arrived in April 1805 and again astonishingly the plan worked. Here, Blamís and his team were able to vaccinate a further 20,000.

This vaccination plan was so successful again, that Balmis took the vaccine to China to keep inoculating the population there too.

Thanks to the ingenious methods of one Spanish doctor and the bravery of 22 Spanish orphans, Jenner’s original vaccine was able to reach the far corners of the world, vaccinating hundreds of thousands and saving countless lives.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments