People are drawn from all over the world to Barcelona’s vibrant cultural attractions, its world-class art, architecture and incredible festivals – which rank among the best in Spain.

But it’s not just what’s in the city that makes it a great place to live, it’s Barcelona’s location too. Situated along the Mediterranean coast, from here you have access to miles of stunning beaches, unlike other landlocked cities popular with foreigners such as Madrid and Seville.

Barcelona even has a large natural park within its limits, offering countless opportunities for hiking and getting out into nature – all accessible by public transport.

Its international airport and location in the top right-hand corner of Spain mean that from here, you have easier access to the rest of mainland Europe too.

And if you’re moving to Spain and hope to find a job, then Barcelona has more opportunities than most cities in Spain (except Madrid) with lots of international companies and even some positions where both Catalan and Spanish are not even necessary.

READ ALSO – Not just English teaching: The jobs you can do in Spain without speaking Spanish

While Barcelona is very high on the list of the world’s best cities for many, like everywhere it does have its drawbacks too. If you’re considering moving to the Catalan capital, here are a few downsides you should be aware of.

There’s a higher cost of living than in other parts of Spain

Barcelona may be a great city, but you’ll pay to live here.

According to the comparison website Kelisto.es, Barcelona is the most expensive city in Spain to live in, with a cost of living 35.51 percent higher than the national average. Housing costs, transport, taxes, shopping and leisure all proved to be more expensive in Barcelona. Of course, wages here are also higher compared to many other cities in Spain, but it’s something you need to be aware of when budgeting for your move.

Petty crime rates are high

Although crime rates in Barcelona dropped because of the lack of tourists due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the city still has a very high petty crime rate compared to some other cities in Spain. In 2019, the city witnessed 299 daily robberies, which equates to 12 every hour. More worryingly, violent crimes were also on the increase and in just the first half of 2019, 5,310 robberies were categorised as ‘violent’.

The most common thefts are pickpockets stealing bags, wallets and mobile phones, but watches are jewellery are sometimes stolen too.

Despite this, on the whole, Barcelona is a relatively safe city. In 2021, it was listed as the 11th safest city on The Economist’s Safe Cities Index, beating the likes of Frankfurt, New York, London, Madrid and Paris.

Rental scams are rife

As well as petty crime, there are several scams that you have to watch out for in Barcelona too. These seem to particularly affect the rental market. If you’ve been in Barcelona a while, you’ll know what sounds too good to be true and what to watch out for, but if you’re new in the city, there are many traps to fall into.

Remember never to sign a rental agreement without having visited the property in person, never hand over any money before you get the keys and if in doubt, get a professional estate agent or lawyer to go over the contract with you.

READ ALSO: What you should know about renting an apartment in Barcelona

You need to learn two languages instead of one

While learning a second language is always a good thing, if you’re new to a country and are learning the language for the first time, it can be difficult to get your head around learning two at once. Catalan is one of Barcelona’s two official languages, meaning that many signs, official documents and menus are not written in Spanish, but in Catalan instead.

While some foreigners can get by only speaking Spanish and all locals in the city will speak it, there are many instances where Catalan will prove very useful. All public schools are taught in Catalan too, so families with school-aged children will inevitably need to learn some Catalan as well as Spanish as soon as they arrive.

READ ALSO – Spanish vs Catalan: Which language should you learn if you live in Barcelona?

Barcelona has its ugly and dodgy neighbourhoods too

Barcelona may be considered to be one of the most beautiful European cities, but it’s not all elegant Modernista buildings and cute little cobbled alleyways; Barcelona has its ugly sides too.

Neighbourhoods such as Raval, some parts of the Gothic Quarter, Sant Adrià de Besòs and La Mina are not the nicest looking. Unfortunately, these are the neighbourhoods that also have some of the highest crime rates, and are not the safest for walking around at night. Drug dealers, narcopisos (drug flats), prostitutes and homelessness are all problems in these areas.

The centre can get very overcrowded with tourists

Before Covid-19 came along, Barcelona often featured on the lists of places struggling with overtourism, and in 2019 the city received a record-breaking 12 million visitors. Tourism bounced back in 2022, with numbers in the summer, already surpassing those of 2019. With a population of just over 1.6 million, this means that tourists can often outnumber locals.

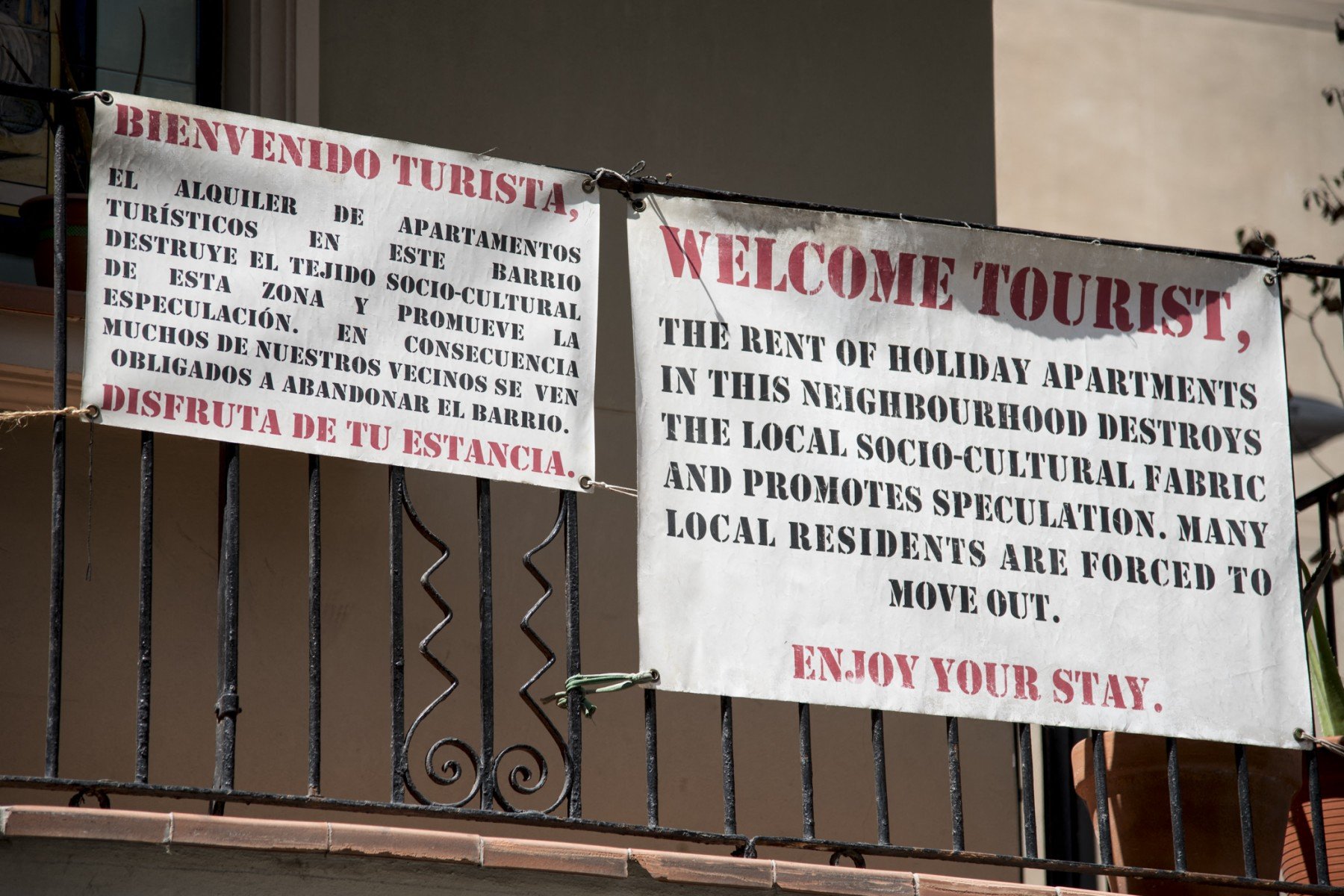

There have been protests against tourists in previous years and you can still see graffiti scribbled across the streets reading “tourists go home”. But the city’s overtourism problem doesn’t just mean that attractions and central streets are crowded, it means an excess of people on public transport when you might be trying to get to work, as well as a lot of extra noise and an increase in prices.

The city can be very noisy

This takes us on to our next point – the city’s noise issue. Tourists are somewhat partly to blame for this, but it’s also the way the city is organised and how its apartments were built.

If you choose to live in places such as El Born, the Gothic Quarter or Gracia – where bars spill out into squares and onto the narrow streets, you’ll find it can be very noisy, most noticeable at night when you’re trying to sleep. Add this to the fact that most old apartments don’t have any double glazing and it will sound like the partygoers are right in your bedroom with you. Thin walls and lack of insulation in most of the older buildings in Barcelona also means that noisy neighbours are a big issue too.

Moving to Barcelona is still worth it

Despite its drawbacks, Barcelona can still be one of the best cities to live in and reward you with many fantastic experiences. Choose your neighbourhood carefully and you won’t have to worry so much about noise, tourists or petty crime and can focus on the reasons that make this city so great.

READ ALSO: 14 Barcelona life hacks that will make you feel like a local

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments