A probe targeting Philippe and two other Le Havre officials was opened in December 2023 on suspicion of influence peddling, favouritism, embezzlement of public funds and workplace bullying, a judicial source told AFP, asking not to be named.

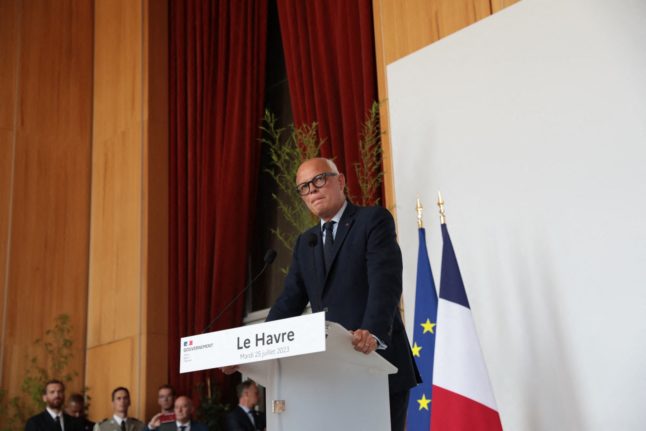

Philippe, who served as premier in 2017-2020, is a close ally of Macron. He runs a centrist movement, Horizons, that is allied to the president’s ruling party.

He is currently seen as the pro-Macron figure who is most likely to stand for the presidency in 2027, as the incumbent leader cannot stand for a third consecutive term.

Philippe has also made little effort to hide his ambitions and some analysts are already predicting that currently the most likely scenario for 2027 is a duel between Philippe and far-right leader Marine Le Pen.

The probe was opened after a complaint that was lodged in 2023 and relates to the setting up of a digital hub in the city known at the Cite Numerique du Havre that aims to encourage innovation.

“We are at the disposal of the magistrates and we will respond to all the questions to show in good faith that we have respected all the rules,” Philippe told the BFM Normandie TV channel, confirming that the searches had taken place.

According to the Le Monde daily, which first reported on the probe, the plaintiff is a former senior official with the local authority whose contract was not renewed by Philippe in April 2023.

Christelle Mazza, a lawyer for the plaintiff, welcomed the searches.

“This is very encouraging for the status of whistleblower and for all public officials who, in the exercise of their functions, including at the highest level, witness facts likely to constitute offenses,” she said.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments