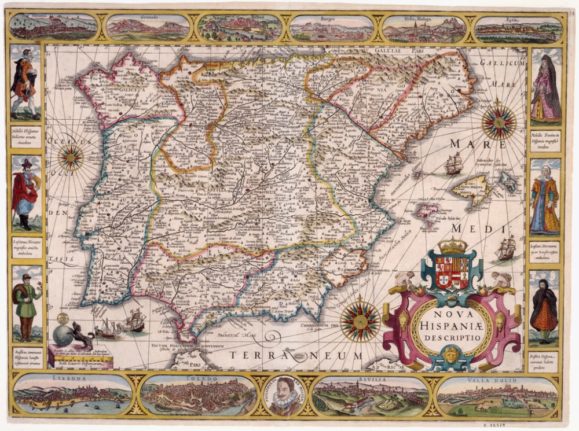

Spain has an important maritime history and during the Age of Discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries, Spain sent its ships all over the world, particularly the Americas and the Caribbean, including to the Aztec Empire in present-day Mexico and the Inca Empire in present-day Peru.

When returning from their voyages of discovery and conquering/pillaging of other lands, they typically brought back ships filled with treasures, from cacao beans and spices to crops such as tomatoes, potatoes, corn, peanuts and pineapples.

But perhaps the most valuable treasures were their hauls of gold and silver.

The archives from the Spanish Navy show that throughout history there have been around 1,580 shipwrecks of Spanish vessels.

Most of these sinkings, according to the documents, are concentrated on the coasts of the Iberian Peninsula and the Caribbean, because of the trading routes between the two places for over three centuries.

According to official data from the Navy, there are 895 ships under Spanish jurisdictional waters.

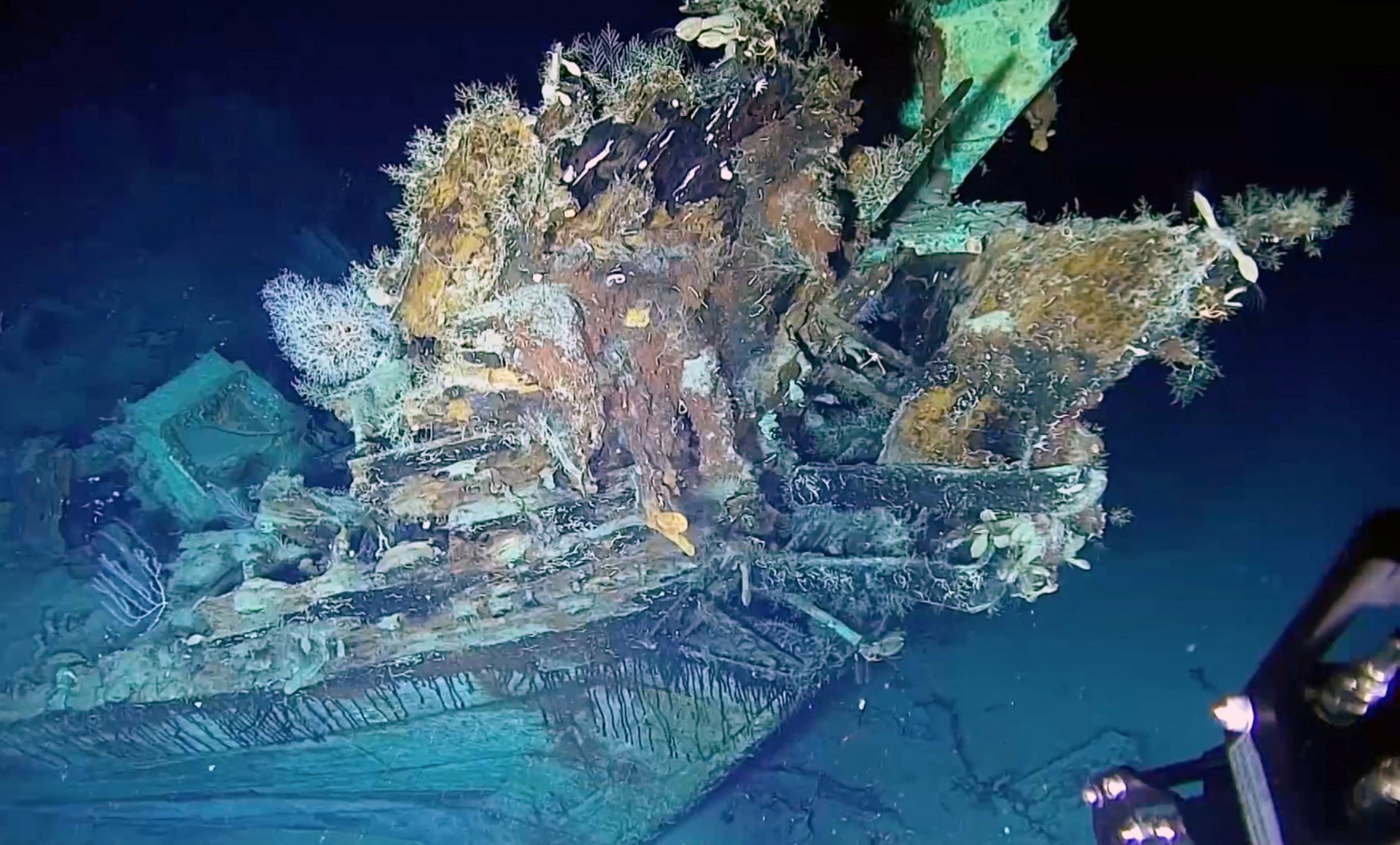

After the discovery of more than 20,000 million gold coins that sank with the Spanish galleon ‘San José’ in 2022, historians and treasure hunters have focused their interest on the location of the wrecks that were part of the Indies fleet, especially that of the 596 ships that are submerged in Spanish waters, particularly in Bay of Cádiz and Galicia.

In fact, experts believe that the seas around the country could be hiding more gold than entire the Bank of Spain.

Between the 15th and 18th centuries, the Bay of Cádiz – and the Port of Santa María was the commercial epicentre for trading with the Indies and it’s here where the largest number of shipwrecks in that period were recorded.

Many of these went down on their journeys home, taking their entire loots of gold and silver with them.

It is estimated that there are around “2,000 tons of gold and more than 20,000 tons of silver in the Bay of Cádiz alone,” historian David Botello told Spanish news site La Sexta.

The current head of the Centre for Underwater Archaeology (CAS) in Cádiz, Milagros Alzaga García fully supports the idea that these ships may have more treasures than the Bank of Spain.

To put this in context, the Bank of Spain, according to the World Gold Council, holds around 281 tons of gold, valued at around €14 billion, which represents one percent of Spanish GDP. This figure would represent 0.8 percent of the 35,000 tons of gold held by central banks.

Alzaga believes, however, that we shouldn’t find the gold in order to sell it and help improve the economy. She likens this to selling off parts of the Alhambra in Granada or La Giralda in Seville and says they are archaeological treasures.

There are also believed to be around 19 Spanish galleons in the waters off the coast of Galicia near Vigo that sank during a battle, bringing back silver from the Americas worth €50 billion.

Pressure is being put on the Galician government by treasure hunters to grant them search permits to go and recover it.

The Spanish Armada has also recorded shipwrecks across Spain’s entire northern coast (especially around the Basque Country), northern Catalonia, in the southern half of Spain’s eastern coast as well as in the Balearic and Canary Islands. That’s right, there are sunken Spanish galleons in almost every coastal province and region.

For example, in the famous Bay of La Concha where the Basque city of San Sebastián is located there are said to be ten sunken galleons. In the Valencia region, mainly in Alicante waters, there are around 100.

But it’s not just the waters around Spain itself that hold riches. The Spanish government has hired Carlos León Amores, an underwater archaeologist, to investigate where all the sunken Spanish ships are in the world.

In ten years of work, Amores and his team have located 66 ships in Panama, 249 in Cuba, 65 in Mexico, and 63 between the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

“In one area of the US we have about 75 shipwrecks of Spanish ships,” he said, adding that the value of the Spanish wrecks that they have managed to locate so far “is incalculable.”

He, like Alzaga, believes that “those pieces should be in museums”, however, “it seems incredible that the black market for underwater treasures continues to exist”.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments