There have been reports from certain media outlets claiming that Spain has the best digital nomad visa in the world.

As we’ve covered Spain’s visado para nómadas digitales in so much depth over the past two years, we’ve decided to carry out our own assessment.

Other than Spain, countries in Europe that offer DNVs are Portugal, Malta, Greece, Georgia, North Macedonia, Hungary, Romania, Iceland, Latvia, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia and Norway.

Then there a number of Caribbean Islands, Latin American countries such as Colombia, Uruguay, Argentina and Brazil, as well as the UAE in the Middle East, Thailand and Malaysia in Asia and even some African nations like Mauritius and Namibia that are offering favourable conditions to foreign talent who want to live and work from their country.

Estimates vary between 40 and 60 digital nomad visas in total, new ones are added every year and some are cancelled or have their perks reduced, as in the recent case of Portugal.

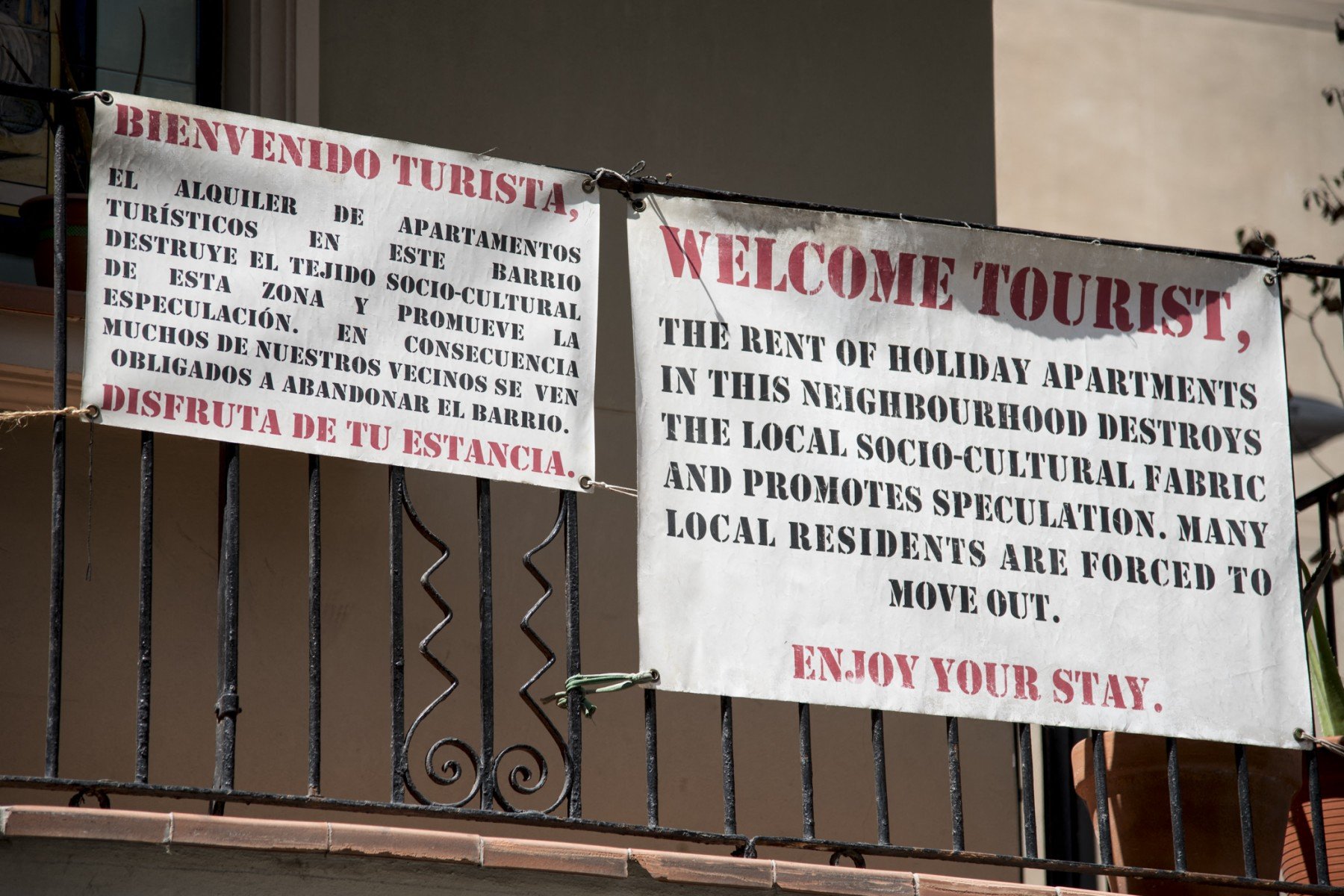

READ MORE: Is Portugal’s ‘anti-digital nomad’ stance a sign of what’s to come in Spain?

In this article, our main focus will be on comparing Spain and its DNV with countries in Europe or those that offer a similar life experience.

So, is Spain’s digital nomad visa the best in the world?

The income requirement is quite low compared to other European countries

To be eligible for the Spanish DNV, you need to prove monthly earnings of at least 200 percent of the minimum interprofessional salary (SMI). The minimum wage in Spain is currently €1,260 per month, which means that you must be able to prove that you will have an income of at least €2,520 per month or €30,240 per year.

This is much lower than some other European countries including Greece which requires you to earn at least €3,500 per month after tax, Portugal which requires you to earn €3,040 and Estonia where you have to earn at least €3,504 gross per month.

Iceland has one of the most expensive requirements for monthly earnings at around €6,644 per month.

But of course, it’s not the lowest amount in the world. Brazil’s DNV only asks for minimum earnings of €1,366.19 per month and for Colombia it’s just €798.82 at the current exchange rate.

READ ALSO: What are the pros and cons of Spain’s digital nomad visa?

It’s not as favourable when it comes to tax breaks

Many countries entice digital nomads with tax breaks and lower tax rates than normal. It was initially thought that Spain would be offering some too, but as of yet, this hasn’t materialised.

The 24 percent flat income tax rate on earnings of up to €600,000 was initially promised to digital nomads (part of the Beckham Law) within the first six months of being in the country, but as of yet, it’s not yet possible to apply for this and standard income tax applies to them. On top of this, any nomads who have to register as self-employed rather than working remotely as a contract worker are not eligible for it.

READ ALSO: How digital nomads in Spain are still waiting for promised low tax rate

Conversely, Greece has introduced a 50 percent reduction in taxes for digital nomads who stay in the country for more than six months.

In Croatia, nomads who are considered Croatian tax residents are exempt from income tax on remote work income but must pay tax on other worldwide income, such as rent from a property abroad.

The Portuguese digital nomad visa for example allows for people to apply for Non Habitual Residence status and benefit from a tax exemption on their foreign-sourced income, as well as a reduced rate of 20 percent tax on Portuguese income. In October, however, the country announced that the current NHR regime will be closed for new applications from 2024, so it remains to be seen whether Porgutal will still be better.

You have to pay high social security contributions in Spain

If you have come to Spain on the DNV and are self-employed, you will generally have to sign up to the autónomo system. This will require you to pay monthly social security payments to cover healthcare and other benefits, which is on top of tax. Spain’s social security payments are one of the highest in Europe, meaning this could be a dealbreaker for some.

For example, anyone earning enough for the DNV will have to shell out at least €340 per month in social security fees in 2024. And if you earn above €2,760 per month, you’ll have to pay even more.

READ ALSO: Is Spain’s digital nomad visa still worth it?

Spain has a relatively low cost of living

If you compare Spain to some other European countries that offer DNVs, it has a relatively low cost of living, especially when looking at prices in Norway, Malta and Iceland for example. According to the cost of living comparison site Expatistan, Malta is 24 percent more expensive than Spain and Norway is 49 percent more.

But when comparing Spain to other southern European countries with the visa – Croatia, Greece, Portugal and Cyprus, you’ll find it’s slightly more expensive.

Of course, the cost of living will greatly depend on where in Spain you choose to base yourself. Living in Madrid, Barcelona or San Sebastián will be much more expensive than if you choose Vigo, Oviedo, Córdoba or Granada. Expatistan states that Granada is 23 percent cheaper than Madrid, while Vigo is 11 percent cheaper than Barcelona.

It goes without saying if you’re comparing Spain with Latin America, Asian or some Caribbean countries that offer the DNV, it’s more expensive. For example, you would generally pay much less in Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico than you would in Spain. Expatistan states that the cost of living is 53 percent less in Colombia than in Spain.

Spain offers a good quality of life and high overall standards

Three Spanish cities – Málaga, Alicante and Valencia – recently claimed all three top places as the best cities for foreign residents in the 2023 InterNations Survey, which goes to show that Spain’s quality of life is vastly appreciated.

Weather, nature, food, friendliness of locals, culture, high welfare standards, good for families, the list of compliments Spain is showered in is abundant, especially among foreigners who don’t have to deal with the dire work market and low wages.

Foreigners who qualify for Spain’s digital nomad visa and have enough to support their families can get free access to Spain’s public education system for their kids. The Hungarian Digital Nomad Visa for example doesn’t even allow for any extra family members.

In the latest World Population Review education rankings, Spain comes in 17th in the world, in front of all other countries offering digital nomad visas in the world, with the exception of Norway.

When it comes to healthcare, whether you have private or public insurance, in Spain it’s generally very good. Those who are self-employed and are registered as autónomo paying into the social security system will be eligible for public healthcare. Most DNV countries on the other hand require you to have private health insurance, while Spain does offer the option for self-employed to be covered by the public scheme.

According to CEOWorld Magazine‘s Health Care Index 2023, Spain has the eighth best healthcare system in the world, beating all other countries in the world that offer DNVs.

In terms of safety, Spain is of course considerably safer than Latin American countries with DNVs but on a par with competitors in Europe and Asia.

It offers a pathway to citizenship or permanent residency

The Spanish DNV offers holders the chance to apply for permanent residency or citizenship in the future if they want to settle down. Visas are initially valid for one year, but enable you to apply for a three-year residence permit, which can be renewed for two further years.

Once you’ve been in Spain a total of five years you can get permanent residency and for most people after 10 years, they can apply for citizenship (this depends on where you’re from and is different for those from Latin American countries and the Philippines).

Greece and Hungary allow digital nomads to stay for one year and extend the residence permit for another 12 months, while Croatia allows you to stay up to one year. Brazil also allows for an initial one-year period, which may be extended for another year.

Verdict

Assessing each and every pro and con of all the DNVs available around the world in order to produce a global ranking is near impossible, not least because it’s subject to personal preferences.

However, Spain’s digital nomad visa is certainly a good choice for budding remote workers on a median income who are primarily seeking a better quality of life with a relatively low cost of living.

On the other hand, Spain’s relatively high tax burden and burdensome bureaucracy might not make it the best choice for everyone, especially high foreign earners.

Is Spain’s the best digital nomad visa in the world? If you factor in all the benefits life in Spain brings – weather, safety, healthcare, nature, cities, food, people, culture – it’s the country itself which might make its digital nomad visa the best available.

READ MORE: The problems Spain’s digital nomad visa applicants face

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments