Spain – the land of sunshine. The country gets between 2,500 and 3,000 hours of sun per year on average, almost double the 1,600 hours the UK gets, for example.

You’d probably assume that finding a bright apartment in such a sunny country would be a piece of cake, but unless you’re renting or buying a modern home, it might be trickier than you realise.

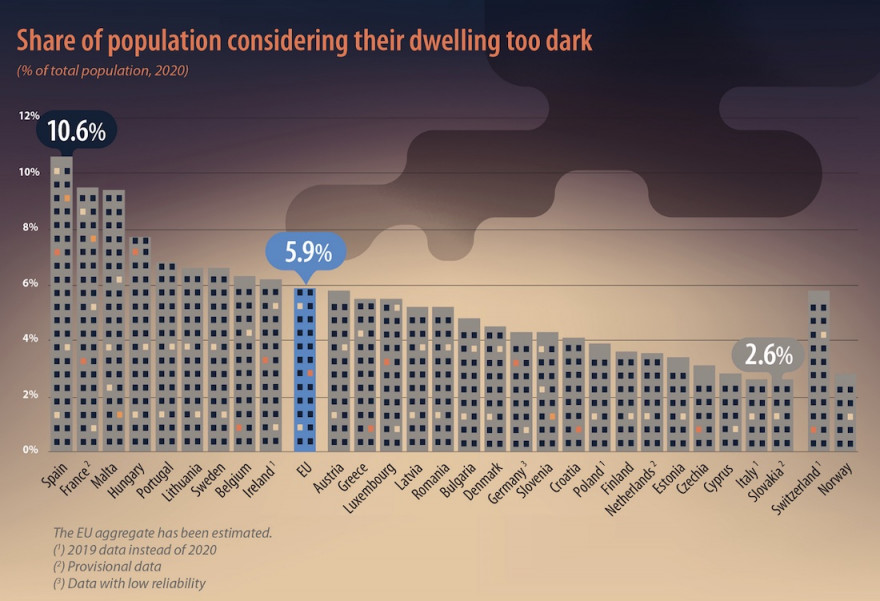

More than one in ten Spaniards live in dwellings they feel are “too dark” – the highest percentage among all EU countries, according to figures from Eurostat.

As far as dark homes go, Spain is head and shoulders above the EU average of 5.9 percent, and higher than other nations with a high rate of gloomy homes such as France (9.5 percent), Malta (9.4 percent) and Hungary (7.7 percent).

At the other end of the brightly lit spectrum, it’s no surprise to see that countries with cloudier skies and darker winters such as Norway, Slovakia, Estonia, Czechia and the Netherlands have homes that let in plenty of natural light, and yet Spain’s sun-kissed Mediterranean neighbours Italy and Cyprus do make the most of the readily available light.

So why are Spanish homes so dark?

Is it a case of hiding away from the sun, and keeping cool during the summer months? Or is it something else?

Apartment blocks

The vast majority of Spaniards live in apartments as opposed to houses, often in tightly-packed cities with narrow streets.

In fact, in Spain 64.6 percent of the population lives in flats or apartments, second in the EU after Latvia (65.9 percent.)

By contrast the EU wide average is 46.1 percent.

By nature of apartment living, Spanish homes tend to get less sunlight.

Depending on whether they have an exterior or interior flat, they might not actually have a single window in the flat that faces the street.

If the apartment is on a lower floor, the chances of it receiving natural light are even lower. Internal patios can help to solve this to some extent, but only during the mid day and early afternoon hours.

Hot summers

During Spain’s scorching summer months, there’s no greater relief than stepping into a darkened apartment building lobby and feeling the temperature drop.

In southern Spain, and in coastal regions, Spanish buildings were traditionally built to protect against the heat and hide away from the long sunny hours. White walled exteriors and dark interiors help to keep homes cool.

It’s often the case that bedrooms are put in the darkest, coolest part of the apartment, sometimes with just a box-window to allow for a breeze but no sunlight.

Spaniards’ obsession with blinds and shutters

Spain is pretty much the only country in Europe whose inhabitants still use blinds (persianas), even during the colder winter months.

In this case, rather than it just being down to keeping homes cool during the sweltering summer months, their usage is intrinsic to Spain’s Moorish past and the fact that they provide a degree of privacy from nosy neighbours. By contrast, northern Europeans with Calvinist roots such as the Dutch keep the curtains open to let in natural light and because historically speaking, keeping the inside of homes visible from the street represents not having anything to hide. But in Spain, the intimacy of one’s home is sacrosanct, especially when the neighbour in the apartment building opposite is less then ten metres away.

Keeping the blinds or shutters down also has the advantage of making it easier to have an afternoon nap (the siesta, of course) or to sleep in late after a long night out on the town.

In any case, it seems hard to believe for some foreigners that many Spaniards are happy to live in the dark whilst spending time at home, regardless of whether they’re sleeping or not.

A by-product of this? Dark, gloomy homes.

The long, dark corridors

Spanish apartments have plenty of quirks that seem odd to outsiders, from the light switches being outside of the room, the aforementioned shutters, the bottles of butane and last but not least, the never-ending corridors.

Most Spanish homes built in the 19th and 20th century include these long pasillos running from the entrance to the end of the flat. They were meant to provide a separation between the main living spaces and the service rooms (kitchen, bathroom etc), easy access to all and better airing and light capabilities. But when the doors to the rooms are closed as often happens, these corridors become the opposite of what was intended: dark and airless.

Navigating these windowless corridors at night is akin to waking around blindfolded.

Are Spaniards rethinking their dark homes?

Times are changing, and modern designs are experimenting with more spacious, light-filled, open-plan apartments, especially as the Covid-19 lockdown forced many Spaniards to reconsider their abodes.

It’s also increasingly common to see property ads stressing that the property is diáfano, which means that natural light enters the home from all sides.

However, the vast majority of Spanish homes are still gloomy for the most part, often intentionally.

A combination of traditional building styles, the crowded nature of apartment block living, the use of shutters, the desire to keep homes private, and the long windowless corridors mean Spanish flats can seem dark if you’re new to the country, and with good reason.

Ultimately, it is worth remembering that Spanish society is one that largely lives its life outdoors. Living in smaller apartments, Spaniards generally spend less time at home and more time out and about in the street.

Native to a hot and sunny country as they are, Spaniards’ homes are a place of rest, relaxation and, crucially, sleep.

Spanish people have enough sunlight and heat in their lives; they like to live, therefore, in homes designed to keep cool and dark.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments