Italy has far fewer recorded cases of monkeypox than some of its European neighbours, with ten infections confirmed as of Thursday afternoon.

READ ALSO: Italian monkeypox cases rise to ten

That puts it significantly behind Spain and the UK, whose health ministries as of Wednesday recorded 59 and 78 cases respectively.

But with the virus spreading across Europe, Italy’s government has started taking precautions, outlining its plans for containment and the treatment of patients in a circular published on Wednesday evening.

The proposals feature a combination of contact tracing, post-exposure vaccinations for health professionals, and antivirals for immunosuppressed people and those with severe symptoms.

Those who come into contact with an infected person will be monitored for symptoms for 21 days from the moment of exposure, during which period they are advised to avoid any contact with pregnant women, children under the age of 12, and immunosuppressed people, the document says.

The circular says that contact tracing will enable the “rapid identification of new cases, to interrupt the transmission of the virus and to contain the epidemic”, as well as allowing for “early identification and management of any contacts at a higher risk of developing a serious disease”.

Healthcare workers and laboratory staff who are considered at high risk may be offered a vaccine “ideally within four days of exposure”, following a “careful evaluation of the risks and benefits”.

The document makes a brief reference to the possibility of quarantine requirements, saying only that self-isolation could be required “in specific environmental and epidemiological contexts, on the basis of the assessments of health authorities”.

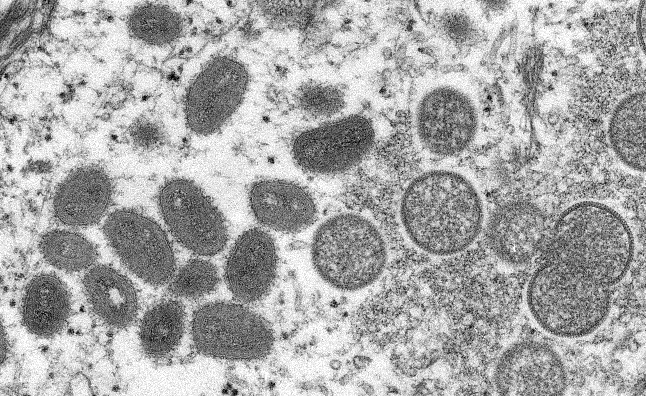

Monkeypox, il vaiolo delle scimmie in Italian, is a rare viral infection that’s endemic to West and Central Africa, and unlike human smallpox, it hasn’t been eradicated.

Monkeypox is not as contagious as Covid-19 and as of yet there have been no deaths associated with this outbreak, but the virus, a milder version of the eradicated human smallpox, isn’t fully understood yet. It has a fatality ratio of 3 to 6 percent according to the World Health Organisation.

As of Tuesday, the organisation had recorded 131 confirmed cases and 106 suspected cases since the outbreak was first reported on May 7th.

Its symptoms are similar but somewhat milder than smallpox’s: fever, headache, muscle aches, back pain, chills, exhaustion, although it also causes the lymph nodes to swell up.

Within one to three days, the patient develops a rash with blisters, often beginning on the face then spreading to other parts of the body.

Monkeypox typically has an incubation period of six to 16 days, but it can be as long as 21 days. Once lesions have scabbed over and fallen off, the person with the virus is no longer infectious.

Although most monkeypox cases aren’t serious, up to one in ten people who contract the disease in Africa die from it, with most deaths occurring in younger age groups.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments