When Germany scored their late equaliser in their nail-biting final group game against Hungary on June 23rd, my dad was unusually quick off the mark.

“Next stop, Wembley,” he wrote to me on WhatsApp. “The question is: who are you going to support?”

As someone who has had to consider relinquishing my British passport in favour of a German one due to Brexit, “which side are you on?” questions are not ones I relish – though I have to admit I’ve played the same game myself.

I moved to Germany from England in September 2016, and given how the dates match up, I often find myself talking about the move as a tiny piece of post-Brexit rebellion, a vote by plane ticket.

If Britain is leaving the EU, I tried to imply to anyone who’d listen, I’m on the side of Europe.

In reality, my decision probably had a lot more with where I wanted to be at the time: my love of Berlin, and the quality of life I felt the city could offer me. And if I’m being really honest, I made the decision way ahead of the June 23rd vote on Brexit.

In reality, I love the UK, and I love Germany. Both things remain true.

And unlike the knock-out stage of a football tournament, identity is not a zero-sum game.

A tale of two commentaries

The internal battle of a fair-weather football fan is not, of course, a particularly big deal.

But the fact remains that, as a migrant in a foreign country, you see the commentary from both angles – and it can sometimes feel like two parallel universes.

READ ALSO: ‘Irresponsible’: Germany urges UK government to reduce Euro 2020 crowd sizes

As the Germans celebrated narrowly clearing the group stages, I braced myself for the onslaught of Faulty Towers references – “Don’t mention the war!” – and evidence of triumphant ‘thrashings’ that England had doled out to ‘the Boche’, dug straight out of the dustbin of sports-trivia history.

"Don't mention Kuntz/Hamann/Penalties…." BRING EM ON! #ENGGER #GERHUN pic.twitter.com/CMWUvwvgP6

— Rex Kramer (@Gagerich) June 23, 2021

Writing in The Guardian a few days ago, Anglo-German sports journalist Barney Ronay pointed out that, while the English media’s response to a play-off against Germany is often reminiscent of the Daily Mirror’s infamous “Achtung! Surrender!” headline at Euro ’96, the German response to these games is generally quite positive.

Anecdotally, the people I’ve met at screenings of the Euros around Berlin have supported this view – though the Germans I’ve talked to aren’t quite so positive about their performance in the tournament so far.

Sitting outside a pub in the district of Lübars over the weekend, one man lamented Germany’s chances against England on Tuesday.

“We didn’t even properly qualify for this tournament,” he told me, adding that he’d be pleased to see England go all the way.

“I’d like to see a small team win it,” he said. “They haven’t won anything for ages.”

England vs. Germany 🏴🇩🇪 This historic fixture has always been something special! 🔥⁰We've seen some terrific games in the past and I'm really looking forward to this match today. ⚽💥⁰⁰Who will make it? England or Germany?⁰⁰#EURO2020 #ENGGER pic.twitter.com/p0lE31D95s

— Bastian Schweinsteiger (@BSchweinsteiger) June 29, 2021

Writing about the upcoming match, Philip Oltermann, The Guardian’s Berlin bureau chief, made a similar point to Ronay about the obsession of the British press with the so-called “old rivalry”.

READ ALSO: Remembering the time Brits turned sleepy spa town Baden-Baden into Germany’s party capital

“Germany’s real grudge matches are against teams that have inflicted painful defeats, like Italy or the Netherlands,” he wrote.

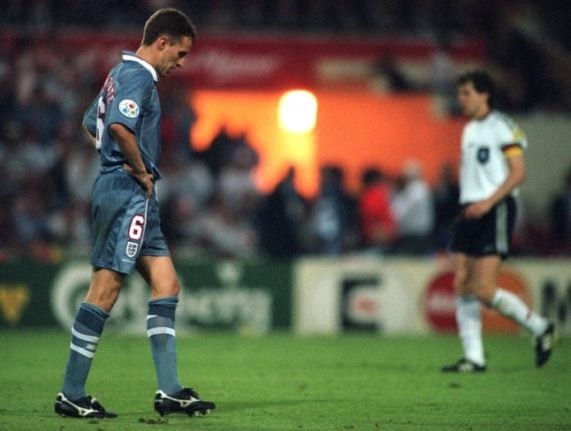

“Matches against England, by contrast, tend to produce happy memories: England have won only six out of 24 matches against West and reunified German teams since 1966.”

In response to the age-old English football chant of “Two World Wars and One World Cup,” Oltermann has an idea for a stinging German counter-attack: “Four World Cups and three European Championships”. And it’s probably a fair retort.

A more respectful tone?

While it doesn’t seem like the Faulty Towers and 1966 World Cup references will ever be avoided in a fixture like this, it seems like international football tournaments are increasingly taking on a different dimension.

Like many other people in our globalised world, German midfielder Jamal Musiala – who could play this evening – is the holder of two passports: a British and a German one.

Midfielder Jamal Musiala, who holds a both a British and a German passport, training ahead of the England-Germany game. Photo: picture alliance/dpa | Christian Charisius

While he was born in Stuttgart and plays for the national German team, he’s also had stints as a youth player for England.

The thing is, Musiala’s international background and ‘Auslandserfahrung’ (experience of living abroad) isn’t particularly exceptional anymore.

Like many expats in Europe, footballers these days have experience of living a split existence: they play for clubs in different leagues and countries around the world, before jetting back home to fight for the home team when the international tournaments kick off.

In a sign of the changing times, the paper which ran the notorious Euro ’96 headline – The Daily Mirror – decided to not to mention Fritz this time around, opting instead for the much friendlier-sounding ‘Hans’.

In a small column about Anglo-German couples, they predicted that, despite the footballing rivalry, most of them would still be able to “shake Hans” afterwards.

Slowly but surely, the migrants and international families around the world are transforming ‘us’ and ‘them’ into a slightly more complicated ‘us’ and ‘us’ – and some, if not all, of the football coverage might be starting to reflect that.

Whisper it quietly, but British today's tabloid coverage of England v Germany today is a far cry from "Let's Blitz Fritz" spirit of 1996. Bawdy, brash and fun, but also respectful. pic.twitter.com/VKd1akdf1i

— Philip Oltermann (@philipoltermann) June 29, 2021

Given what we’ve seen in the tournament so far from both teams, I wouldn’t be brave enough to place a bet on the outcome of the England-Germany game tonight, but I do have one prediction (or ‘Tipp’, as the Germans would say).

While jingoism may not crash out of the Euros with a bang tonight, it could slowly but slowly be petering out of the England-Germany discourse. Though we’re not quite there yet.

Having left my dad hanging on the “who will you support” question, I finally think of a response that feels right.

“Whoever wins,” I tell him. Which feels like a win-win scenario.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments