Spain and Ireland first officially established diplomatic relations in 1529, when the Ambassador to King Charles V of Spain visited Irish shores and signed the Treaty of Dingle.

This gave citizenship rights and other privileges to Irish exiles and migrants in Habsburg Spain and other Habsburg territories from the 16th to the early 20th century.

Spain had in effect become a powerful ally of the Irish, they shared the same Catholic beliefs and a common enemy in England.

Gaelic leader Hugo O’Neill even offered the Irish crown to Philip II of Spain as a means of staving off the English, but the Spanish King turned the offer down.

What Spain did do was stick to its offer of refuge to Irish rebels during the 100 Years War, as it did in 1607 in the exodus of Irish leaders that’s known as the Flight of the Earls, and later during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in the 1640s.

And so began the most important first waves of Irish migration to Spain, most of which were well-to-do families whose descendants were to have a considerable impact on Spanish and in particular Canary politics.

As documented in the General Archive of Simancas in Valladolid, they mainly came for religious and political freedoms – particularly to escape persecution from the English, but also to seek new commercial and merchant opportunities.

Many important Irish families migrated to Spain’s Canary Islands from 1651 onwards for this very reason.

The White, Power, Molowny, Meade, Kelly and Murphy families, whose surnames are seen in streets and square placards in the archipelago to this day, set up shop in the biggest towns of Las Palmas, Puerto de la Cruz, Santa Cruz de Tenerife and Santa Cruz de La Palma.

By the 18th century they’d established themselves as some of the most powerful merchant families on the islands for their trade with the Americas.

Some of the most prominent of these Spanish-Irish figures – who by that stage were combining a Spanish name with Irish surnames in impeccable exotic style – was José Murphy y Meade.

Born in 1774 in Tenerife’s capital, he is known as the “Father of Santa Cruz de Tenerife” for getting Spain to allow the city to become a free port, something which enabled the archipelago to prosper as a trading post, and has no doubt played a part in the Canaries still having an independent VAT system to this day.

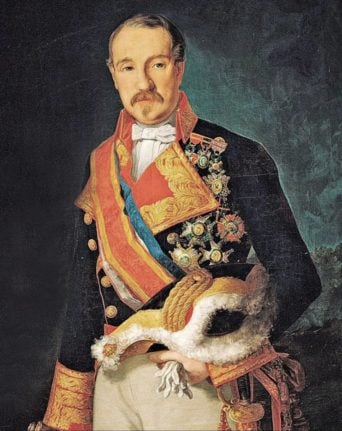

Then there was Leopoldo O’Donnell (pictured below), also born in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, and who served as a general and statesman before becoming Prime Minister of Spain. Madrid residents will be interested to know that that Irish sounding metro station is named after this very O’Donnell.

Dionisio O’ Daly, a merchant who was born in Cork but moved to the island of La Palma, made history after his campaigns led to the first democratic town hall elections in Spain ever.

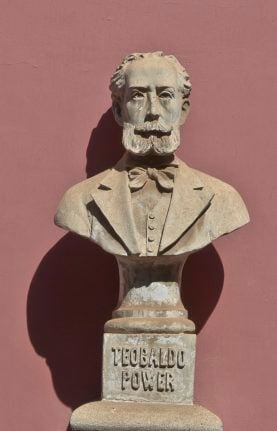

And on the arts front there was Teobaldo Power, born in Tenerife in 1848, a renowned composer of the time who’s remembered as one of the Canaries’ most important historical figures.

Other prominent Canary figures of Irish roots include brothers Agustín, Manolo and Totoyo Millares Sall – renowned poet, painter and musician respectively, or Canary president in the late 80s Lorenzo Olarte Cullen.

The list can go on with Irish surnames, or ‘Spanishised’ versions of them, still prominent in Canary society – testament to perhaps the finest example of Irish integration in Spain.

READ ALSO: Where do Spain’s Irish residents live?

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments