April 23rd, 2019 is Tag des Deutschen Bieres (German Beer Day), which marks the 503rd anniversary of the creation of the world’s oldest food regulation.

That regulation, known as the Reinheitsgebot – or beer purity law – laid out the framework for Germany to become a proud beer nation – a pride that remains as today.

To celebrate German Beer Day, the German statistical agency – Destatis – have released the 2018 beer consumption statistics, showing what’s trending when it comes to the country’s favourite tipple.

We looked at the history right up until the modern day to figure out just why a big ol’ jug of beer means so much to Germany.

First and foremost, 2018 saw an increase in consumption by 2.2 percent over 2017 figures – helped largely by the long hot summer and Germany’s World Cup exit.

See also: German brewers toast 500 years of the beer purity law

A toast to the world’s oldest food regulation

Specifically, the Reinheitsgebot required that beer be made from three ingredients and three ingredients only: water, barley and hops. Yeast wasn’t known at the time, but was later added to the list when its important role in brewing was discovered.

The Reinheitsgebot was laid down in 1516, making the world’s oldest food regulation. The man responsible was Munich’s Duke William IX, who became worried that beer was being adulterated with other ingredients like sawdust, soot and poisonous plants.

Half a millennium ago, the result of the food regulation was to improve beer quality – and the law is still having the same effect today.

As reported by The Local in 2016, while “sawdust, soot and poisonous plants” aren’t as frequently a problem in modern beers, other additives like sugar, preservatives, flavours and enzymes are.

By upholding the standard, German beer makers can guarantee drinkers drink a higher quality drop – something which becomes even more important the morning after.

All of the above additives increase the risk – and the impact – of a hangover. We’re not saying a German beer will be hangover free, but by avoiding all those extra additives your head will thank you come the morning.

See also: Why the German beer renaissance is in full swing

A kick to the hip pocket?

Beer in Germany remains far cheaper than in many other countries – however that is gradually changing.

Last year beer prices rose by 3.5 percent more than the rate of inflation. Perhaps surprisingly, craft beer was not to blame – with the largest price increases coming among the mainstream German beers like lagers, pilsners and dark beers.

Wheat beer and alt-beer prices saw the smallest increase, going up by 1.8 percent respectively.

A restriction on innovation and creativity: Last drinks for the Reinheitsgebot?

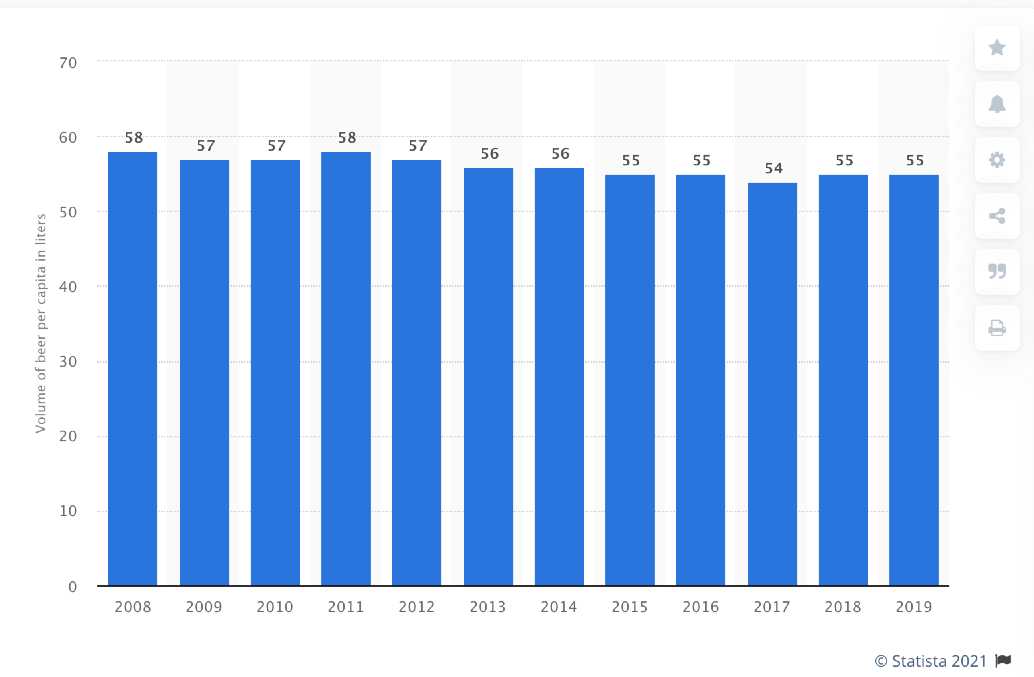

While consumption of beer has decreased in recent years in Germany, the number of breweries is on the rise. This is primarily because while Germans are drinking less beer, they are becoming more discerning in their taste – leading to the rise of craft beer.

Some craft brewers have complained that the Reinheitsgebot restricts their creativity – as they are effectively restricted to four ingredients. Advocates of reforming or removing the law argue that the brewery culture in neighbouring Belgium has flourished despite the lack of such a regulation.

As per the law, beers including fruit or other additives produced in Germany are not allowed to be called ‘beer’. While larger brewers have been able to get around this by using their brand name and omitting the word beer – Beck’s Green Lemon anyone? – smaller breweries trying to experiment while getting a foothold may find it more difficult.

Varieties of German ‘craft beer’ have exploded in recent years. Image: DPA

A 1987 ruling of the EU Court of Justice ruled that the regulation was a protectionist measure, which meant that the law could not be used to prevent the import of beers not brewed according to the law – an important step almost 20 years later when Germany hosted the Budweiser-sponsored FIFA World Cup. Unlike German beers, the mass-produced American Budweiser also includes rice.

Marc Oliver Huhnholz, a spokesperson for the German Brewers Association, disagrees. Huhnholz told The Local in March “Craft beer and (the) Purity Law are not a contradiction. On the contrary,” he said.

“Just as the first craft brewers in the US began using the natural raw materials of the Purity Law some 40 years ago, even today most of the craft beers are brewed with water, malt, hops and yeast alone.”

Either way, there’s little chance of the rule being changed anytime soon – almost nine out of ten Germans polled believe it should stay a valid part of the German law.

Bavaria remains the king when it comes to beer production

For most of the world – and much to the frustration of the residents of the country’s 15 other states – Bavaria means Germany and Germany means Bavaria.

While this is not true in 99 percent of cases – the only lederhosen you’ll spot in Frankfurt or Berlin will be on an American tourist – Bavaria remains the home of German beer.

Lederhosen. Das ist so (not) Berlin. Image: DPA

Of the 8.7 billion litres brewed in Germany in 2018, just under a third comes from Bavaria (2.4 billion litres). The populous North-Rhine Westphalia sees the second highest production with 23 percent (2 billion litres), with Baden-Württemberg producing seven percent (0.6 billion litres).

The remaining 13 German states produce 3.7 billion litres (42 percent) between them.

There were 654 breweries in operation in Bavaria in 2018, more than three times as many as second-placed Baden-Württemberg (206 breweries).

A drink to have when you’re not having a drink

To many foreigners – particularly those from Anglo-Saxon cultures – the idea of a beer without alcohol seems a contradiction in terms.

Indeed, the refrain “there’s nothing so lonesome, morbid or drear; than to stand in the bar of a pub with no beer” makes up the chorus of one of Australia’s most celebrated national songs, with singer Slim Dusty certainly not referring to the alcohol-free variety.

But in Germany, beer’s omnipresence in society necessitates an option for those seeking the refreshment and social component of the amber fluid but without the alcohol and its subsequent side effects.

Alcohol-free beer is increasingly marketed as a sports drink in Germany. While it might seem odd to see a group of cyclists riding past with an alcohol-free wheat beer in their drink holder, the drink has isotonic properties as well as a range of other minerals like maltodextrin and magnesium are reported to help soothe the muscles after activity.

As a result, the sales have skyrocketed in recent years. Now, every 20th bottle of beer produced in Germany is alcohol free, with 400 different options available.

Italy the biggest international market for German beer

The beer market has a considerable amount of value for the German economy. In 2018 1.6 billion litres of beer – worth €1.2 billion – was exported, an amount largely unchanged when compared to the previous year.

The biggest export market for German beer in 2018 was Italy, with 21.8 percent (344 million litres) of beer exported south.

China (11.3 percent) and the Netherlands (7 percent) were the countries next on the list.

And while Germany remains a proud beer nation, the country isn’t averse to imports. Germans imported 718 litres of beer in 2018, with the biggest source country being Denmark.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments