For a decade, the 62-year-old who long worked as a psychic in the northeastern region of Catalonia where Dalí was born, has tried to prove she is the painter's child.

Her paternity claim, however, has raised scepticism, with Dalí biographer Ian Gibson writing in El Pais that he had doubts, saying the artist preferred watching rather than having sex.

But Abel is adamant her mother had a relationship with Dalí, one of the most celebrated and prolific painters of the 20th century, when she worked for his friends in Port Lligat, a tiny fishing hamlet.

The painter lived and worked there for years.

READ MORE: Six surreal facts about the life of Salvador Dalí

Abel told AFP a judge's decision on Monday to exhume Dalí's remains was “a big victory” though she acknowledged there was still a long way to go.

The Dalí Foundation which manages the artist's estate has said it will appeal.

“At last I would know who I really am and would be recognised,” she said.

“I don't want his heritage, if it comes so be it, but it's the last thing I want. First of all I want my identity.”

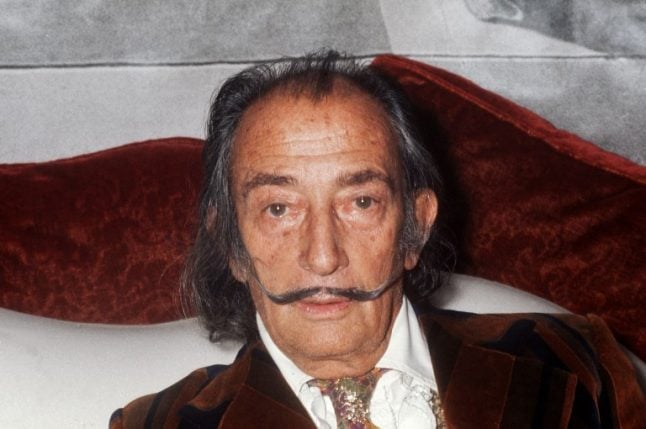

Is there a family resemblance? Pilar Abel believes so. Photo: AFP

Exchanging glances

She said her grandmother first told her she was Dalí's daughter when she was seven or eight years old, and her mother admitted it much later.

Abel is from the city of Figueras like Dalí, and she said she would see him in the streets often.

“We wouldn't say anything, we would just look at each other. But a glance is worth a thousand words,” she said.

Notoriously eccentric, Dalí's life was marked as much by the genius of his work than by his own extravagances.

A question mark has always hung over his sexuality.

Writing in El Pais, Gibson said he had once spoken to a gay Colombian gallery owner called Carlos Lozano who knew Dalí well and told him the painter was homosexual but incapable of acting on it.

He also said Dalí could not stand anyone touching him, bar his muse and long-time partner Gala.

Lozano recalled orgies at Dalí's house during which the artist would merely watch, Gibson says, adding it was “possible” that he had sex with a woman, though he doubted it “very much.”

But according to Abel's lawyer Enrique Blanquez, the affair was “known in the village, there are people who have testified before a notary.”

By Daniel Bosque /AFP

READ MORE: Salvador Dalí to be exhumed over paternity claim

Photo: AFP

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.