Sniggering at foreign words that sound rude is an extremely childish pastime. But it’s also fun, so here we go with a look at some of France’s funniest place names.

While some of these are only funny to English-speakers, there is a scattering of French towns that sound pretty hilarious in French too.

Misery

Let’s face it who’d want to live in a village called Misery?

This one’s a double whammy; not only is ‘misery’ a negative term in English, but in French, misère means poverty or destitution (so Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables are poor and destitute, rather than ‘the miserable ones’ – although his classic novel does contain plenty of misery too and living in poverty is not exactly fun).

Still, approximately 137 people can proudly say ‘j’habite à Misery’ and you too could experience Misery if you travel to the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region.

Stains

The town in the Île-de-France region claims it gets its name from the Latin ‘stagnum‘ (pond), as apparently there are many in the area.

However, it’s more likely to make Brits think of dirty marks – not to mention the London commuter town Staines, whose reputation was ruined by Sacha Baron Cohen’s character Ali G.

For the French, Stains has a different negative connotation – the town has high levels of poverty and unemployment and recent headlines have been around shootings and police violence.

Anus

Fancy living in the arse end of nowhere?

It’s a mystery as to why this small town in Burgundy has kept its decidedly unglamorous name, since ‘anus’ has the same meaning in French as in English (un anus, it’s masculine in case you ever wondered and is pronounced an-oos).

But apparently the inhabitants aren’t bothered by having to tell people they live in Anus. Maybe they’re relaxed about life because they live in one of France’s most famous wine-producing regions?

Dole

‘On the dole’ is a British term to describe someone collecting unemployment benefits, so moving here might seem like a bad omen for your career – on the bright side, France is a better place than most to be unemployed (or en chômage in French).

More than 25,000 people call Dole home, and its main claim to fame is as the setting for French comedy Happiness is in the Field (Le Bonheur est dans le pré), telling the story of a toilet seat factory-owner with family troubles.

Dives

‘Dive’ is English slang for a run-down, cheap and dirty area. Sometimes used in a positive sense by hipsters or college students who prefer ‘dive bars’ to overpriced clubs, nonetheless it doesn’t sound like somewhere you’d choose to live.

Having said that, we’re sure that Dives in the Oise department, as well as Dives-sur-mer in north-western France, are much nicer than their names suggest. It’s pronounced ‘deev’ and has nothing to do with diving, which is plonger in French.

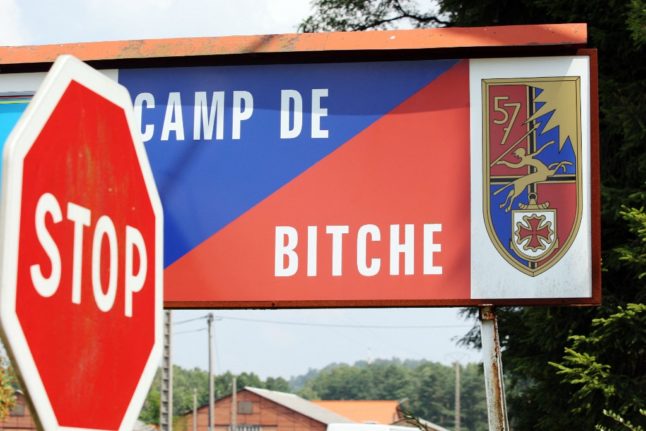

Bitche

Life really is a bitch here. The town of Bitche in eastern France, near the border with Germany, lies in an area known as ‘Bitche Country’, or ‘Bitscherland’ in German. In French, the inhabitants of the town are referred to as ‘bitchois’, suggesting they’d make pretty unfriendly neighbours.

The town has a long military history but unfortunately most English speakers won’t be able to stop sniggering at the name long enough to learn about it. Bitche has even featured as an answer on British comedy panel show QI, and the town council also lost its Facebook page when Facebook HQ decided that it was offensive.

In French the closest word to ‘bitche’ is biche – a perfectly inoffensive term for a female deer, that’s also sometimes used as a term on endearment. If you want to get offensive and refer to a woman as a ‘bitch’, that would be connasse.

Angers

Angers is a relatively large French city with 147,305 inhabitants, universities and museums. Its name comes from the Latin word Andecavi, which was the name given to people from the region, and through linguistic change it has become ‘Angers’ in today’s French.

It’s pronounced on-zjeyre and has nothing to do with anger. The French, you may be unsurprised to hear, have a lot of terms to describe being angry, annoyed, pissed off or furious. Probably the most common is en colère – literally ‘in anger’ which you will see on a lot of protest signs.

10 of the best French phrases for when you’re angry

La Grave

Surely only someone particularly morbid would enjoy living in a place called ‘Grave’?

Even in French, the meaning is ‘serious’, often used in a negative sense about an illness or injury. But 487 people live in La Grave, and the area is popular with off-piste skiers and ice climbers who apparently enjoy having not just one, but both feet in the grave.

Very commonly heard in French is c’est pas grave – it’s not serious, which you would say when someone apologies to you. It’s like ‘don’t worry about it’ or ‘it’s nothing’

Pis

You’d have to wear wellies all year round if you lived in Pis.

Pis, in the Gers department of south-western France, is encircled by the river Auroue, and gets 180 millimetres of rainfall each year.

Although the French word ‘pisse‘ has the same meaning as English ‘piss’, the French tendency to drop final consonants probably means they don’t see the schoolboy humour in this town name, which is pronounced ‘pee’ – still pretty funny for English-speakers.

Craponne

The name of the town says it all really.

‘Crap’ is one of England’s most commonly-used swear words, and a series of books called Crap Towns chronicles the worst places to live in Britain. We wonder if Craponne would feature in a French edition?

More than 10,000 people live there and it hosts an annual country and western music festival.

The French language does have an excellent rude word that literally means to ‘crap on’ (or shit on) someone – emmerder.

Bony

The town where the residents need a good feed.

Whether used to describe someone who is unhealthily thin, or a cut of meat that doesn’t actually consist of much meat, ‘bony’ is usually used in a negative context in English. But it is also the name of a small French village in Picardy, home to just over 100 residents.

Essay

Where the kids are constantly doing homework.

Living in a town called Essay would give most English speakers flashbacks to dull homework and exam panic – surely you’d never feel truly at ease. Though it’s home to only 513 people, Essay is much more exciting than its name suggests; it is known for its motorsports tracks and also offers go-karting.

In French your written homework is more likely to be called a dissertation or a production écrit, although essai is also used.

Essai has a more positive meaning too, though – in rugby it’s a try (a goal) from the verb essayer (to try).

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

There’s a place near us (in Deux Sevres) called Largeasse, which always makes me giggle.

The French word “grave” is now used in slang to mean “good” or “super” or “awesome,” much the same way “terrible” or “malheur” or even “tuerie” can connote something positive. Here’s an interesting webpage on some otherwise incomprehensible French slang. https://www.lefigaro.fr/langue-francaise/expressions-francaises/2018/06/08/37003-20180608ARTFIG00007-grave-un-tic-de-langage-a-bannir.php

Pêt d’âne isn’t funny in English but it’s certainly funny in French! It’s in the Côte Roannaise, in Dancy (also a fun name), 42.

https://www.roannais-tourisme.com/nature-outdoor/spots-nature/le-pet-dane/

it’s also a pastry, according to Wikipedia.fr, aka Beignets d’Amiens. I’ve never come across them. Possibly something like Pêts de nonnes? More fun names….the French can be quite scatalogical, I guess.

how about veillemorte near Ruffec – a village that watches the dead

Hadn’t heard of some of these, they did make me laugh! You could have added the town of Condom, too. Up in the Somme is the hamlet of Y, which is twinned with the Welsh village of Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch. Clearly the twinning team had a sense of humour…