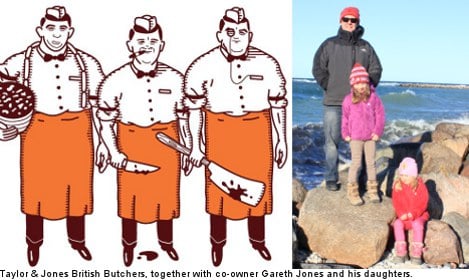

Gareth Jones came to Sweden in 1996 and swiftly started working as a chef at a British pub in Stockholm. After a few years of running a couple of restaurants in the capital, he teamed up with Irish butcher David Taylor in 2007 to create Stockholm’s first British butchers, Taylors & Jones.

In the shop, which is located on Kungsholmen in Stockholm, Jones, Taylor and third partner Kerim Akkoc offer customers over 40 different types of sausages to choose from, as well as meats, cheeses and other specialties from the British isles.

The company also delivers to shops and restaurants across the country, as well as organize sausage-making courses and catering services.

The Local: So, why did you first come to Sweden?

Gareth Jones: It was the ususal reason, really. I met a Swedish girl while I was working in Greece and then followed her back to Sweden.

TL: What did you do before coming here?

GJ: I had actually been travelling around in Asia, Australia and Europe working in kitchens for something like eight years prior to coming to Sweden.

TL: What did you do when you first came to Sweden?

GJ: I sort of walked into my first job actually, as a chef at the Beefeater pub in Stockholm.

TL: How long did it take you to learn Swedish? Is that important for an expat?

GJ: It took me about two years to become fluent in Swedish. I think that it is crucial to learn the language. Foreigners sometimes get stuck moving in the same expat circles and just end up moaning about the country they’re in. If you want to be able to laugh with people you must share their language.

TL: How did you begin doing what you are doing now?

GJ: The idea behind an establishment like Taylors & Jones is one that I had had almost from day one in Sweden. But it wasn’t until I had sold off two restaurants that I was part-owner of that I was finally in a position to make it a reality. And David Taylor, the other co-owner, had approached a friend of mine with a similar idea – and he was referred to me.

TL: What was the easiest/most difficult thing with trying to ‘make it’ in Sweden?

GJ: I really think that Swedes are open to new ideas and that makes it easier to start something new and different here. When we first opened we had a lot of British and expat customers, but to be honest, we wouldn’t have been able to manage just on that. It was when the Swedes found us that things really started moving.

The most difficult thing I guess is all the rules and regulations that you have to get through to start your own company here.

TL: What are the keys for an expat to ‘make it’ in Sweden?

GJ: The key to making it in Sweden is the same as anywhere else, really – hard work. Also, as a foreigner setting up a business one must work harder in the beginning. Later it may even work in your favour that you hail from somewhere else, but in the beginning you must really prove yourself.

TL: What would be your advice to someone thinking about trying to start a company or do their own thing in Sweden?

GJ: I think it is important to try to learn the language as quick as possible. Also, when starting your first company in Sweden, it isn’t a bad idea to team up with a Swede who already knows how things work here. That certainly helps when it comes to getting advice on all the regulations.

TL: What do you like most about Sweden? What do you hate most?

GJ: I love the quality of life that we enjoy here. We all moan about everyday things, but then we can go away and enjoy a four-week holiday. I also love the sort of “country-house culture” that exists here, where a lot of people have their own place in the country to retreat to on the weekends and during their time off.

What I do find difficult, though, is how people don’t talk to each other. I have to go home to Wales to get my dose of everyday friendliness. And when I return it’s difficult to get back in the swing of ignoring people again, as is done here a lot of the time.

TL: Here at The Local, we have an on-going feud regarding the word elk versus the word moose. How would you best translate the Swedish word älg to English? Say, in the sentence: “there is definitely no älg in this sausage”?

GJ: Well, I think the correct way of saying it would be elk, though I know the American usage of the word moose is taking over. I would definitely say elk.

Rebecca Martin

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments