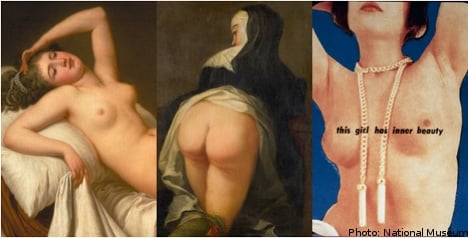

To much fanfare, Sweden’s National Museum on March 23rd opened a new exhibition entitled “Lust & Last” (Lust & Vice). The exhibition is marketed as a 500 year journey through the artistic representation of eroticism and is intended as a comment on how society’s mores have shifted.

“There is a lot of naked painting in this exhibition. During the work before the opening of the exhibition, we have fielded a lot of questions as to why naked painting is so prominent within western art,” Eva-Lena Bergström, head of exhibitions at the museum, explains in a promotional film.

The exhibition proposes an exploration of “How the limits of what is considered immoral have changed throughout history and how it looks today?”, promising visitors a “Naked Shock!”.

And a veritable feast of human flesh is indeed what is on offer in the National Museum’s grandiose exhibition halls.

The exhibition is dominated by a host of biblical, allegorical and mythological scenes – much of which would pass unobserved in a more traditional art exhibition, but in “Lust & Vice” are deliberately placed to create a contrast with modern work and mores and to encourage the onlooker to question traditional art history.

“How have we looked at the pictures, who is the subject, and who is the traditional object. The woman has often functioned as a model, and also the object for the male gaze… Artists working in the late 1900s have deliberately experimented with our norms and values,” Eva-Lena Bergström says.

But with the public domain liberally dominated by the naked human form, more often than not the female human form, critics have been swift to question whether the museum is motivated more by commercial factors and whether the exhibition is designed for artistic reflection at all.

“It is the most banal exhibition I have seen in ages. It mixes overtly erotic pieces with themes such as love and betrayal, without rhyme or reason. It has the effect of making everything heavily sexualised. In the end everything becomes vice, even the desire becomes vice,” art critic Katarina Wadstein Macleod tells The Local.

Criticism of the exhibition has pointedly not taken the form of any sort of “feminist moral panic”. It has instead reflected more a resigned frustration among gender theorists that the exhibition’s presentation simply serves to further reinforce the objectification of the female form and the hegemony of the traditional male gaze, rather than challenge its predominance.

“There are no clearly expressed ideas nor critical reflection on the images it presents. This applies not just from a gender theoretical perspective, although the absence of this is deeply problematic,” Stockholm University researchers Malin Hedlin Hayden and Jessica Sjöholm Skrubbe argue in a debate article in the Dagens Nyheter daily on March 31st.

Sjöholm Skrubbe and Hedlin Hayden’s article sparked a broader debate in the media which, while giving further publicity to the exhibition, largely centred on the curatorial work in putting the exhibition together, a point on which Katarina Wadstein Macleod concurs.

“It is a question of selection (and presentation). The message of norm critical work becomes sullied by mixing extremely critical pieces in an environment of fantasy paintings. It becomes just a mixture, the critical edge disappears,“ she says.

While the exhibition is dominated by depictions of the female form, with a plethora of feminine behinds on show, the male organ makes its presence felt, none more so than in the work of 18th century artist Carl August Ehrensvärd and his pornographic series “On life’s arduous rampage”.

The series of sketches accompanied letters sent by Ehrensvärd to embellish the story of his wife’s adventures in Copenhagen and are displayed in the exhibition next to a work entitled “This girl has inner beauty” by Lotta Antonsson, which depicts a critical comment on the superficiality of physical beauty.

“What is an obviously norm critical piece loses its message when placed alongside some erotic sketches, for no apparent reason,” Wadstein Macleod says.

The opening of “Lust & Vice” coincided with the censorship of a nude painting by Swedish artist Anders Zorn posted by a Danish artist Uwe Max Jensen on Facebook. In the ensuing controversy, Jensen accused the firm of imposing US “cultural imperialism” on a global audience by striving to determine the distinction between pornography and art.

Jensen’s argument that Scandinavian moral codes were distinct and more liberal than their US equivalent was shared by numerous commentators in the Swedish media and cultural circles.

By challenging visitors to “Come and test their own limits” of what they consider immoral, the National Museum enters this discussion, apparently questioning whether perhaps Sweden really is as liberal as one might have thought.

Eva-Lena Bergström argues that some of the 18th century art on display would challenge even contemporary attitudes towards nudity and eroticism in the public domain.

“Much of this art… was never intended to be painted for or shown to a public audience – it was painted by men for men,” she says.

The exhibition pits a body of work from the 17th-19th centuries together with some examples of work from contemporary artists, such as Lars Nilsson and his film of a young woman lying on her back in the forest masturbating.

Nilsson’s work encourages the viewer to become the voyeur, and judging by bumper visitor figures milling through the National Museum’s turnstiles, the Swedish public is prepared to accept the moral challenge and can weather the promised “Naked Shock” – something which comes as no surprise to Katarina Wadstein Macleod.

“Sex always sells. The question is what kind of sex they are selling?”

Check out The Local’s “Lust & Vice” gallery here.

The “Lust & Vice” exhibition will continue until August 14th 2011 at the National Museum on Blasieholmen in central Stockholm

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments