For a country with such long and controversial history, colonialism doesn’t figure in modern-day discourse in Spain as often as one might expect.

And if it does, which it can occasionally, it’s not nearly as controversial an issue as in other former colonial powers in recent years, such as in Britain.

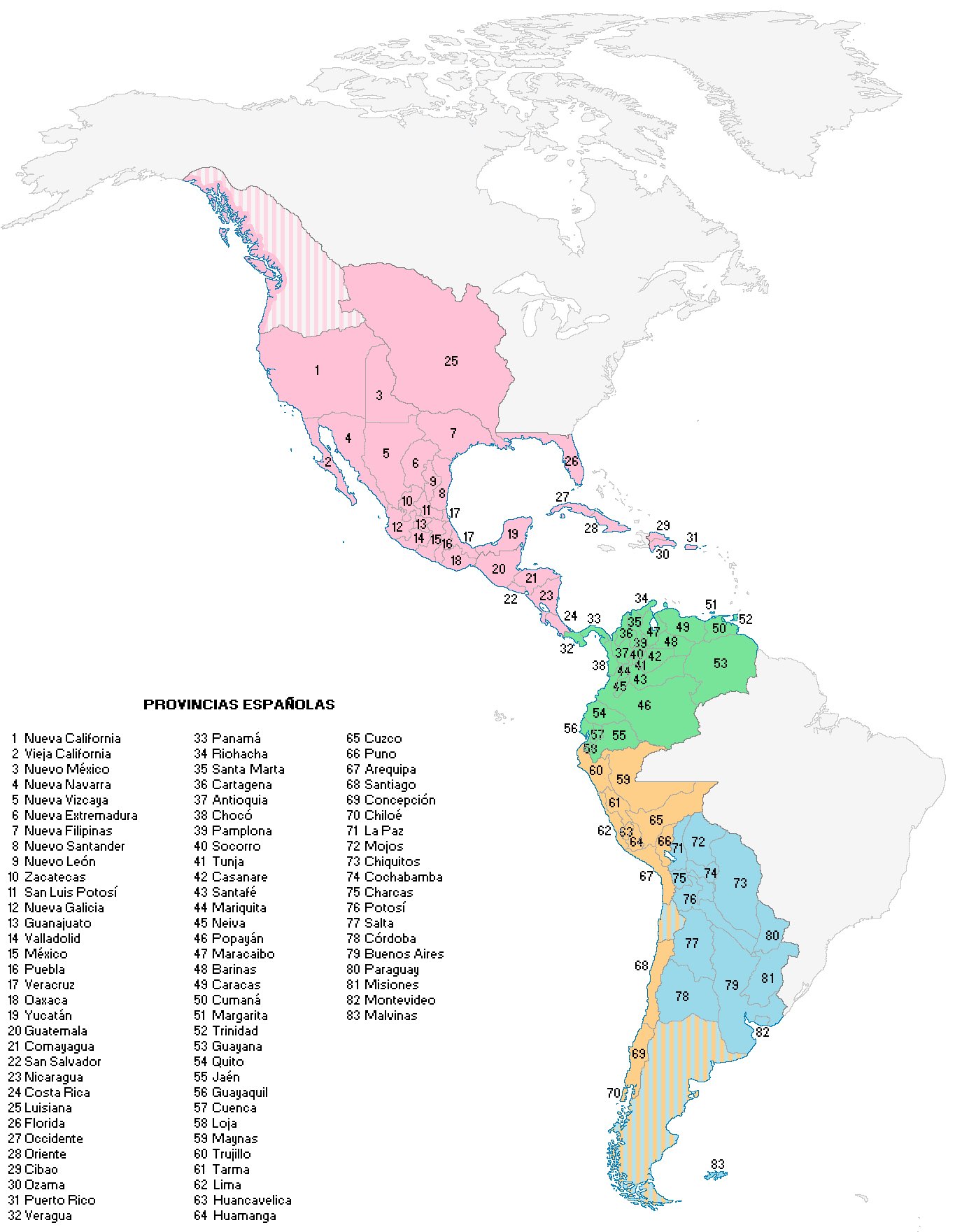

It is often claimed that Spain didn’t even have any colonies at all, and that it instead had ‘viceroyalties’ (virreinatos in Spanish).

When contemporary standards and values are projected onto the past it is for present-day political ends, but in Spain this isn’t just a position held by the political right, nor only in Spain.

In fact, many Spanish and Latin American historians alike are persuaded by the idea that Spain didn’t have colonies, and if it did, not in exactly the same way other empires did.

Some also argue that the barbaric behaviour of Spanish conquistadors in the New World was born, in part at least, from the leyenda negra (black legend) propaganda pushed by imperial rivals.

Normally this is quite a niche historiographical debate confined to journal articles and books.

But in recent weeks debate about Spain’s colonial past has become more prevalent again after Spanish Culture Minister Ernest Urtasun, from the far-left party Sumar, decided Spain should go the way of other western states and ‘decolonise’ its museums.

The aim, Urtasun says, is to “overcome the colonial framework” and “make visible the perspective of the communities and peoples from whom the exhibited works originate come from.” But some historians have ridiculed the idea and described Urtasun as talking about “colonies that Spain never had.”

Colonies or viceroyalties?

Much of the debate stems from a disagreement over historical definitions.

A viceroyalty is a territorial entity removed from central court and governed on behalf of a monarch by a ‘viceroy.’ There were also viceroyalties in Catalonia and Sicily, for example, just as there was the viceroyalty of ‘New Spain’ based in modern day Mexico from the mid-1500s.

The distance between Spain and its viceroyalties meant that viceroys, courts and royal audiences were created to essentially try and mirror or mimic rule in Spain, and viceroys sometimes served as intermediaries between Spanish and native elites.

A colony, on the other hand, generally summons more negative connotations, usually as an exploited territory dominated by a foreign power that violently extracts wealth and resources without mixing with or attempting to integrate the native population.

“Spain never had any colonies”

The difference between colonies and viceroyalties may seem like semantics but it’s a distinction that historians themselves don’t even agree on.

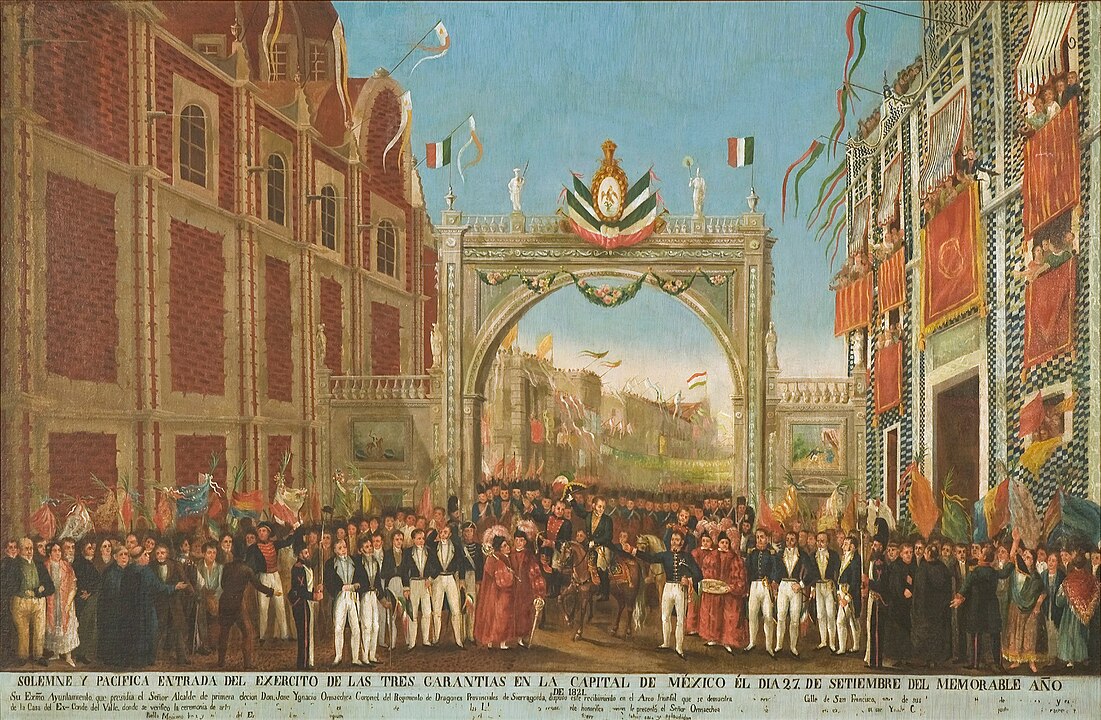

Of course, it almost goes without saying that by today’s standards the Spanish conquistadors committed countless war crimes in their crushing of the Inca empire and capturing of the continent.

Many would argue by spreading diseases that killed millions of native people, the Spanish empire is guilty of the biggest genocide in history.

All of this is true, but separate from the more technical historical debate between colonies and viceroyalties.

The debate seems to have taken off with the 1951 publication of “The Indies were not colonies” by Ricardo Levene, an Argentinian historian.

María Saavedra Inaraja, historian and Director of the CEU Elcano International, told Spanish (right-wing) newspaper ABC that Urtasun “does not seem to know our history well, as he talks about colonies that Spain never had.”

Even left-wing news outlet La Sexta has quoted Spanish writer Miguel Ruíz Montañez as sharing similar beliefs: “Spain never had colonies, anyone who was born in Mexico or Venezuela or Colombia at that time was a subject of the Spanish crown just like any Valencian or person from Málaga.

“Even Native American Indians had the same rights as natives in the Iberian Peninsula,” says the writer.

Enrique Krauze, a Mexican historian, has said that “it must be made clear that there are many differences between the colonies that the European powers established in Africa in the 19th century and the viceroyalties of the Americas.”

He also points to the fact that it’s not only Spanish historians who have come to this conclusion: “There is a vast amount of historiography written not only by Spanish historians, but also by English, American and Mexican researchers,” he says, “which explains that these two forms of government were far from being the same.”

The thread running through these arguments is essentially that Spain’s overseas territories were not run in the same way as in other empires, notably the British, and that the alleged legal equality (despite the millions who dies) means that the Spanish territories in Latin America were not colonies in the traditional sense.

In that way, perhaps a good way to think about the difference is that some would argue Spain transported an entire state infrastructure (courts, universities, churches, and so on) to its territories, whereas the British simply pillaged them and took what they wanted back to Britain.

British colonists did not mix with the native population, were reluctant to miscegenation (sexual relationships or reproduction with other ethnic groups), something the Spanish certainly weren’t, and deprived the native population of wealth and technology they brought with them from the old world. In other words, a clear separation between colonists and the colonised.

Spanish viceroyalties, some suggest, were considered at the time as provinces of the empire, and therefore the local people had the same rights as any other province in peninsular Spain.

Of course, this sounds like a rose-tinted view of history and post-colonial and revisionist historians would argue that Spain’s territories in the Americans fit all the criteria for colonies: the extraction of resources and wealth, widespread violence and rape, the imposition of language, religion and culture, and, as mentioned, some would say genocide.

Modern-day politics

But this isn’t just a debate contained within historiography. Spain’s colonial past is also an increasingly political issue. However, unlike the debate between historians, the colony versus viceroyalty debate splits pretty neatly along traditional left-right divides in Spanish politics.

When Urtasun talks of “overcoming a colonial framework or one anchored in gender or ethnocentric inertias,” his political opponents claim he is regurgitating the “black legend that you have internalised.”

Right-wing Partido Popular deputy María Soledad Cruz-Guzmán told Urtasun that “we both know that Spain did not have colonies,” while a far-right Vox member pointed to the 27 universities Spain built in Latin America and the “same rights” that native peoples allegedly enjoyed.

Urtasun, for his part, has stated that “if anyone thinks it is wrong for us to incorporate this reading of history, let them say so. It does not mean rereading history, it means understanding different readings, such as the incorporation of the vision of the indigenous peoples.”

As such, the government will carry out a review of collections in some state museums, notably the Museo de América and National Museum of Anthropology to try, as Urtasun says, “overcome the colonial framework.”

The only problem is that some in Spain deny their old empire ever had any anything resembling colonies at all.

Furthermore, a closer look at the Spanish empire’s many other ‘exploits’ in Asia, Europe and Africa – from the Philippines to the Netherlands and Mozambique – also serves to prove that not all of Spain’s former territories were viceroyalties.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments