It follows the return last year of seven works of art stolen from Grunbaum in 1938 and sold by the Nazis to fund their war machine.

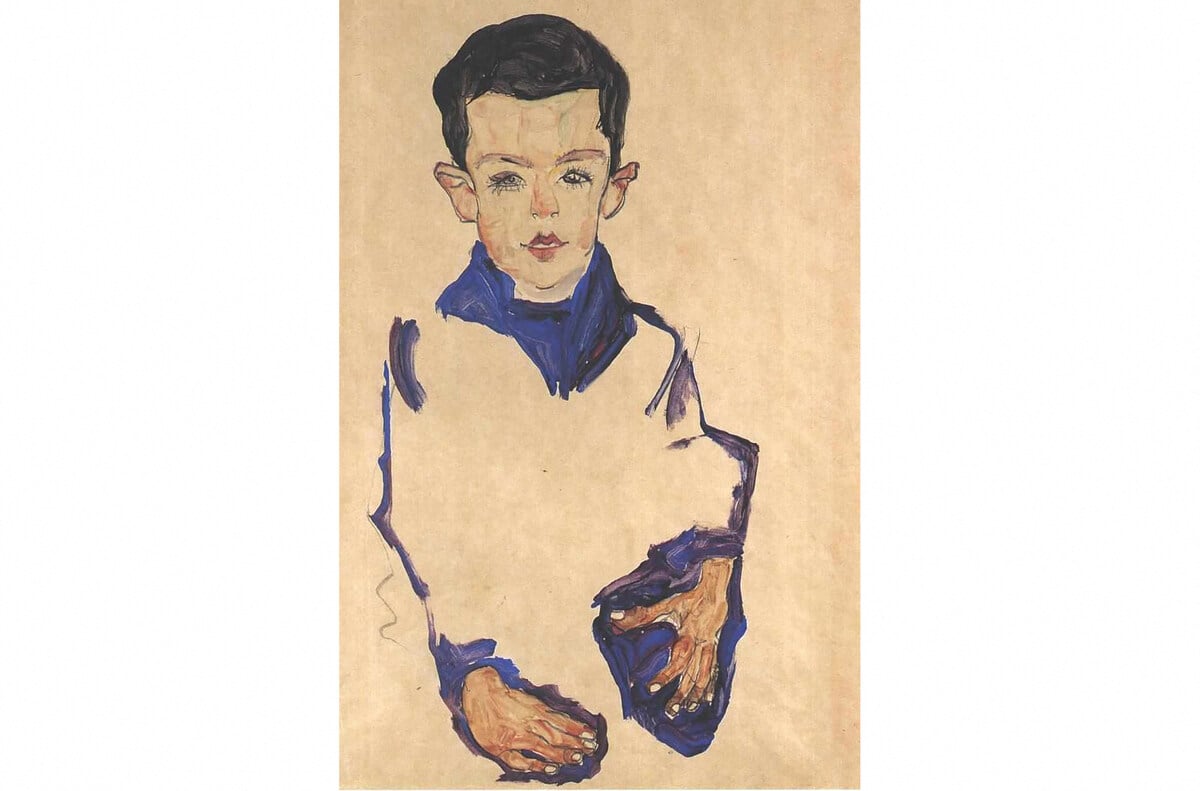

“Girl with Black Hair” had been held by the Allen Museum of Art at Oberlin College and is valued at approximately $1.5 million, while “Portrait of a Man” was in the Carnegie Museum of Art collection and valued at approximately $1 million.

They are both by Egon Schiele, an Austrian expressionist artist.

“This is a victory for justice, and the memory of a brave artist, art collector, and opponent of Fascism,” said Timothy Reif, a judge and relative of Grunbaum who died in Dachau concentration camp.

“As the heirs of Fritz Grunbaum, we are gratified that this man who fought for what was right in his own time continues to make the world fairer decades after his tragic death.”

In addition to the seven returned last year and the two latest pieces to be handed back, one piece was surrendered by a collector directly to the family.

“The fact that we have been able to return ten pieces that were looted by the Nazis speaks to the dogged advocacy of his relatives to ensure these beautiful artworks could finally return home,” said Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg.

Grunbaum, who was also an art collector and critic of the Nazi regime, possessed hundreds of works of art, including more than 80 by Schiele.

Schiele’s works, considered “degenerate” by the Nazis, were largely auctioned or sold abroad.

Arrested by the Nazis in 1938, Grunbaum was forced while at Dachau to sign over his power of attorney to his spouse, who was then made to hand over the family’s entire collection before herself being deported to a different concentration camp, in current-day Belarus.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments