The Great War had a significant impact on Chantilly, a provincial horse-racing town some 37 km from Paris, where 1,200 of the 5,500 residents in 1914 were of English origin – the majority being descendants of the original horse-racing families who came over from England in the 1830s and 40s, to build the now-famous racecourse, forest gallops and set up training stables in the area.

When Britain and France went to war with Germany at the beginning of August 1914, it was at a time when young men thought it was their duty to sign up and fight for their country.

In France, you needed your parents’ consent to enlist if you were under 21, even though the age to voluntarily enlist was 17. Most racing staff had dual nationality and got round this problem of avoiding the parents’ consent by enlisting for the British Army where this was not a requirement.

This was the case for Fred Meggs, whose father was English and mother French. Born in 1899 he was unable to join the French Army without his parents’ authorisation – to get round the problem Meggs joined the British Army in 1917. He was injured the same year and finally returned to Chantilly in 1919.

Others were not so lucky and from the just under 1,000 men who enlisted, 187 died while many others were badly injured.

The Anglican St Peter’s Church in Chantilly, originally built and paid for by the horse-racing community in 1865, has two stained glass windows in memory of its congregation who died during the First World War.

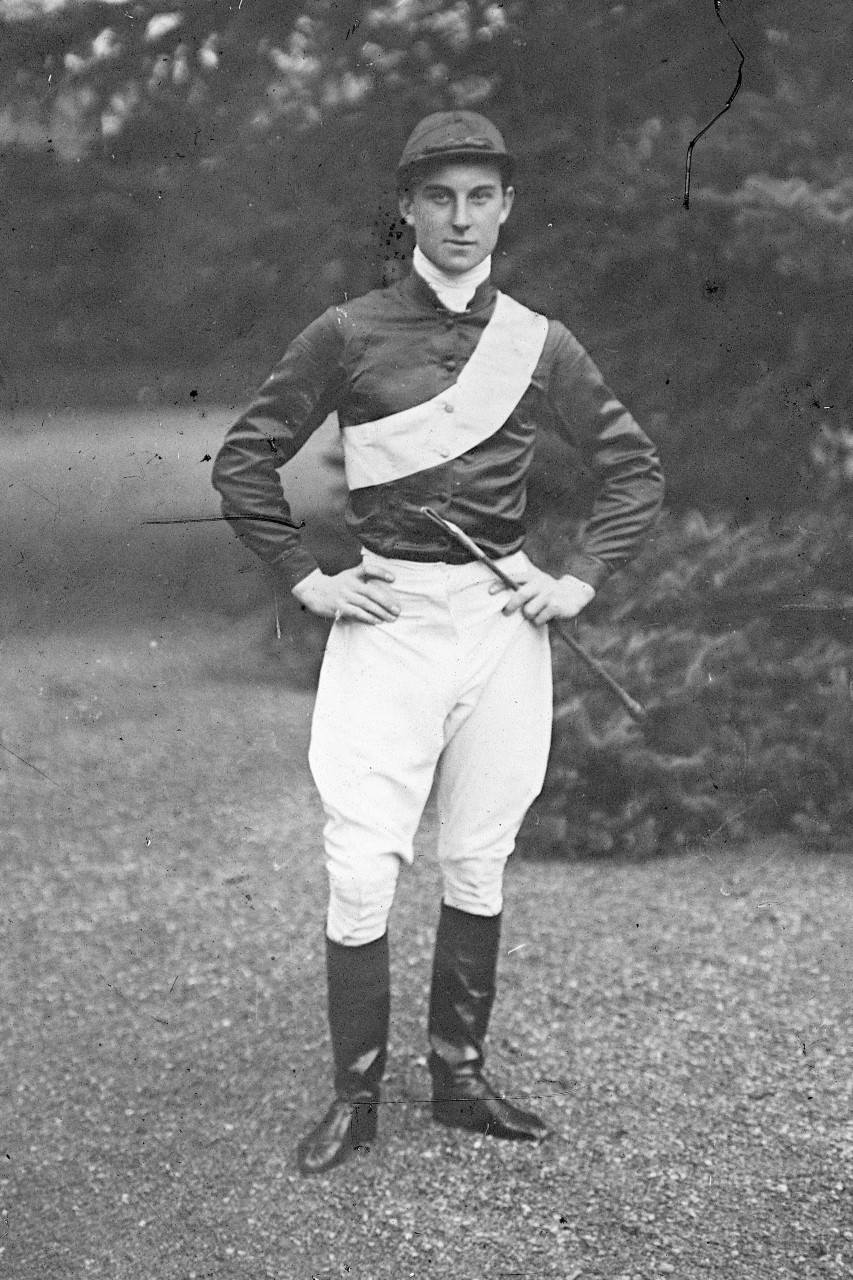

They include Alec Carter – a famous jump-jockey related to the Carter family who were one of the main contributors’ in developing Chantilly as a racecourse and training centre. His father was Fred Carter a leading trainer as were his grandparents Thomas Carter and William Planner.

Alec Carter had won the Grand Prix de Steeplechase at Auteuil riding Lord Lorris for owner James Hennessy, just two months before war broke out.

He joined up immediately and two months later wrote to a friend; J’ai l’impression de mener une vie sans encombre. Bien que quatre chevaux étè tués sous moi, je n’ai pas égratignure. (I have the feeling of living an unhindered life. Even though i have had four horses killed under me, I don’t have a scratch.)

A few days later, as second lieutenant in the 226 regiment, he was seriously wounded following an attack at Saint-Pol-Ternoise Pas-De-Calais. He died two days later on October 11th aged 27. He was awarded a special military medal inscribed “Excellent officer who has made a number of attacks and always acquitted himself with conscience and courage.”

He is buried in the family grave at the Bois Bourillon Cemetery in Chantilly.

Also in the British army was Herbert Attwood, who served with the 18th Lancashire Fusiliers and was fatally wounded at the Somme, dying a few days later on 31st July 1916 and buried at the British Commonwealth cemetery at Corbie near Amiens. His battalion was a special troop for soldiers less than the regulatory 5ft 3 inches tall.

Trainer George Batchelor and his wife Matilda Watkins lost their only son Gerald George Batchelor, a promising young jockey before the war. He was badly injured at the Somme, and died shortly afterwards in a London Hospital on March 17th 1917, aged 22.

Richard Johnson, born in Compiegne, was in Germany war broke out – studying languages at the Handelsschule School in Hamburg. After war was declared Johnson was put in a concentration camp for foreigners.

“His grandfather Richard Carter managed to get him out on a forged American passport provided by an American banker friend,” explained his grand-daughter Carolyn McCartney.

Johnson on his return immediately enlisted in the British Army and received the Military Cross from King George V in December 1919 for his outstanding bravery while serving as second Lieutenant in D Battery in the 160 Brigade Royal Field Artillery in Geluwe (West Flanders, Belgium).

After the war, Johnson served in the army of Occupation in Cologne, Germany before being discharged in 1921 to become assistant trainer to Elijah Cunnington in Chantilly.

During the war, Chantilly’s racecourse and its surrounding pelouse were closed and occupied by the French military, who also used the nearby Les Aigles training centre for aircraft pilot practice.

The German Army entered Chantilly on September 3rd 1914, briefly occupying the famous Château before departing the next day for the Battle of the Marne.

Still, it was a tough time for Chantilly as the town had to cope with the influx of refuges from northern France and Belgium. By 1915 they had 159 refugees who were put up in the Hospice Condé retirement home.

Chantilly also became a hospital centre for wounded soldiers, initially at the Hotel Lovenjou and the Egler Pavilion, but as numbers increased tents were erected on the pelouse area around the racecourse.

In 1917 much-needed employment became available for women in Chantilly when 1,200 were hired by the military to paint the canvases which the army used to hide artillery and troop movements.

The French used Chantilly as a military headquarters – taking over the six-floor Hotel Du Grand Condé and other hotels in the town to accommodate 450 officers and 800 clerks and soldiers.

General Joseph Joffre held a conference at Chantilly in December 1916 with his Allied counterparts, to organise the military strategy for the following year. Joffre didn’t last long – replaced by General Robert Nivelle after heavy defeats at Verdun and the Somme.

The headquarters were subsequently moved to Beauvais to be nearer the fighting and Nivelle himself was replaced by General Philippe Pétain in May 1917.

At the beginning of the war all types of horses were being requisitioned by the military – including Grand Steeplechase winner Lord Lorris who was killed in action. Too late for him and many other horses, it was realised after a few months that cavalry charges against heavy artillery were useless.

A number of racehorses were saved by their owners sending them to trainers in England, but war took its toll on the thoroughbred population in Chantilly with 1,600 horses in training at the beginning of 1914 and just 553 in January 1918.

No horse-racing took place in France between 1914 and 1916, which caused tremendous difficulties for trainers who had to cover their costs without racing taking place, few staff available and horse feed scarce.

In 1916 the French racing authorities managed to convince the military to allow horse-racing to take place at 154 country meetings.

The other issue was finding jockeys to ride, as many were away fighting for their country. This problem proved to be an opportunity for American jockeys in France – many of whom had come over in the early 1900s after becoming disillusioned with American horse-racing – as the country didn’t enter the war until 1917.

Most notable was the American Frank O’Neill who was French champion flat jockey 10 times between 1910-1922, including 1914 and 1916.

It took about three years after the war for Chantilly to get back on its feet again, and the leading training families such as the Batchelors, Carters, Cunningtons, Watsons, Jennings, Counts and many others linked to horse-racing, to recover from the effects of the war.

The loss of life will never be forgotten, and certainly remembered by descendants this weekend paying their respects.

John Gilmore is a freelance journalist and photographer who has lived in Chantilly for 20 years.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments