The IMF has published its first global economic forecasts of the year, and according to ITS projections, Spain will be the European economy that will grow the most in 2023 and 2024 (among large economies), which includes Germany, France and Italy.

However, this should be tempered somewhat by the realisation that these projections, though positive overall, are actually slight downgrades to Spain’s previous GDP forecasts. In fact, the Spanish economy was the only major Eurozone economy to have its forecasts downgraded, despite still leading the pack.

READ ALSO: Spain posts strong growth for 2022 despite inflation

According to the IMF figures, Spanish GDP is now expected to grow by 1.1 percent in 2023 and 2.4 percent in 2024, which represents a 0.1 percent decrease on previous predictions for 2023 and a 0.2 percent decrease for 2024 forecasts. These are the highest rates among the larger European economies though.

These figures differ quite significantly from the Spanish government’s own forecasts, however. In the government’s General State Budget (PGE) for 2023, growth was predicted to be 2.1 percent – almost double.

Taking the IMF’s figures, Spain would not recover its pre-pandemic production volume until 2024. The latest GDP data, released by the INE last week, still puts Spain 0.9 percent below the figure for the fourth quarter of 2019.

Along with the Czech Republic, Spain is the only country that has not fully recovered from the blow inflicted by Covid-19.

Yet, despite that, and despite its downgraded forecast, the IMF still believes that the Spanish economy will grow the most among larger European economies.

The expected GDP growth of 1.1 percent in 2023 is ahead of projections for Germany (0.1 percent), France (0.7 percent) and Italy (0.6 percent) as well as being 0.4 percent above the wider Eurozone average forecast, which is 0.7 percent.

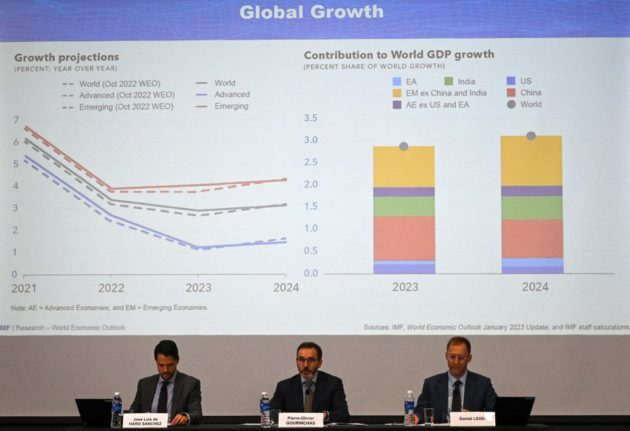

Global outlook

According to the IMF figures, global GDP growth will slow to 2.9 percent in 2023 after growing by 3.4 percent in 2022. Production looks set to pick up in 2024 with a projected increase of 3.1 percent, but still a way off the average figure for the 21st century – 3.8 percent. The IMF points out that global GDP was “surprisingly solid” in the third quarter.

In terms of inflation, the IMF believes global inflation will gradually fall from 8.8 percent in 2022 to 6.6 percent in 2023 and 4.3 percent in 2024. All economic indicators seem to suggest that inflation has peaked and will continue to fall as the prices of fuels and raw materials decline.

“The rise in central bank interest rates to combat inflation and Russia’s war in Ukraine continue to hinder economic activity,” the IMF said, adding that the recent ending of China’s ‘zero-Covid- strategy “has paved the way for a faster recovery than anticipated”.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments