Spain’s Health Ministry on Tuesday confirmed 51 monkeypox cases so far, placing the country ahead of Portugal (37) and just behind the United Kingdom (57) in terms of confirmed infections.

It also means that Spain is currently the non-endemic country with the second highest number of monkeypox infections in the world.

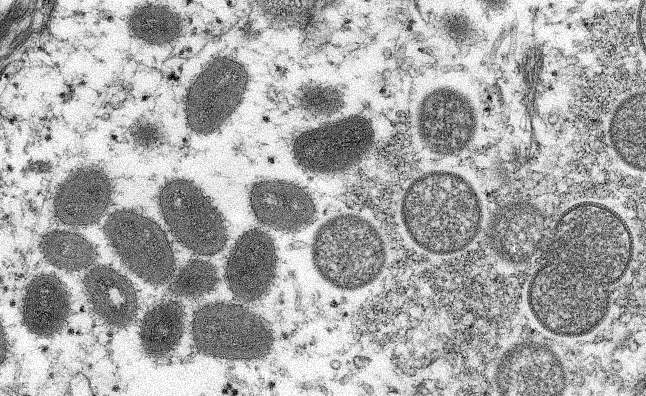

Monkeypox is not as contagious as Covid-19 and all cases in Spain so far haven’t been serious, but this virus, a milder version of the eradicated human smallpox, isn’t fully understood yet. It has a fatality ratio of 3 to 6 percent according to the World Health Organisation.

At least 160 monkeypox cases have been confirmed in May 2022 in non-African countries where the virus isn’t endemic, almost all in Europe: mostly Spain, the UK and Portugal and with single-digit cases in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, Italy and Switzerland.

The unprecedented outbreak of this monkeypox virus has put the international community on alert. On Monday, the European Union urged Member States to take steps to ensure positive cases, close contacts and even pets be quarantined, as this is a zoonotic virus (a virus that spreads from animals to humans).

Spain’s monkeypox protocol

On Saturday, Spain’s Health Ministry published an early detection and prevention health protocol for the monkeypox outbreak, with health officials due to meet again on Tuesday to evaluate further measures.

People infected with the virus in Spain should self-isolate in “separate rooms” as well as avoid physical contact and sexual relations with others “until the lesions have disappeared”, as monkeypox produces rashes with blisters as in the case of smallpox.

Spain’s action protocol also requires infected people to wear a face mask and that they have to go out to seek medical attention that they use public transport.

Recent cases of the virus in Europe are thought to have been spread through sexual activity but according to the CDC “human-to-human transmission is thought to occur primarily through large respiratory droplets”, which explains the mask requirement. Transmission via bodily fluids, lesions or through contaminated materials such as bedding is also possible.

Close contacts of positive cases in Spain do not have to quarantine but they should also “constantly” use a face mask in public, Spain’s Health Ministry writes, as well as take extra precautions and reduce social interaction.

People infected with the monkeypox virus should cover and care for their wounds and there should be adequate hand hygiene with soap or hydroalcoholic gel by members of the same household.

The Health Ministry considers close contacts to be people who have had contact with a confirmed case, “less than a metre away” from them in the same room and without a mask, or if they’ve shared clothing, bedding or other objects.

Spanish health authorities also state that infected people should “avoid contact with wild or domestic animals”, in the sense that “pets must be excluded from the patient’s environment”.

Smallpox vaccines

There is no EU-approved monkeypox vaccine for Spanish health authorities to purchase currently, but according to Spanish national daily El País, Spain’s Health and Defence ministries are to buy 2 million vaccine doses for the traditional smallpox virus at a cost of €7.2 million.

Vaccines for smallpox have an 85 percent effectiveness rate against monkeypox according to the WHO, as the two viruses are members of the same family.

This vaccine is not intended to be administered to the general population, but rather only to close contacts of confirmed cases if infections continue to rise.

Monkeypox, la viruela del mono in Spanish, is a rare viral infection that’s endemic to West and Central Africa, and unlike human smallpox, it hasn’t been eradicated.

Its symptoms are similar but somewhat milder than smallpox’s: fever, headache, muscle aches, back pain, chills, exhaustion, although it also causes the lymph nodes to swell up.

Within one to three days, the patient develops a rash with blisters, often beginning on the face then spreading to other parts of the body.

Monkeypox typically has an incubation period of six to 16 days, but it can be as long as 21 days. Once lesions have scabbed over and fallen off, the person with the virus is no longer infectious.

Although most monkeypox cases aren’t serious, up to one in ten people who contract the disease in Africa die from it, with most deaths occurring in younger age groups.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments