Reader question: I read recently that the guillotine was still in use in France during World War II – is that really correct? When did France stop using it?

Hamida Djandoubi was convicted of the kidnap, torture and murder of 22-year-old Élisabeth Bousquet in February 1977, and executed by guillotine at Baumettes Prison, Marseille, in September that year.

The 27-year-old achieved three grisly distinctions in death; he was the last person to be judicially executed in France, the last to be judicially executed in western Europe, and the last to be judicially executed by beheading anywhere in the western world.

He was not the last person in France to be condemned to death, however. Philippe Maurice, convicted of complicity in murder and the murder of law enforcement officers, was the last person in France to be handed the death penalty in October 1980.

He was pardoned by new President François Mitterrand, a noted anti-death penalty campaigner, four days after his inauguration in May 1981. His sentence was commuted to life in prison – having gained a doctorate in medieval history while in prison, Maurice, now 65, is a respected historian.

Months after Maurice’s highly symbolic pardon, in October 1981, France abolished the death penalty and the last seven people to be sentenced to death had their sentences commuted.

The last person to be publicly executed in France was serial murderer Eugen Weidmann, who was guillotined outside St-Pierre prison in Versailles, on June 17th, 1939.

In total, 34 people were executed in France since the foundation of the Fifth Republic in 1958.

The last woman to be beheaded in France was Germaine Leloy-Godefroy in 1949, some years earlier in 1943 Marie-Louise Giraud was guillotined under the Vichy regime – which made abortion a capital crime.

First victim

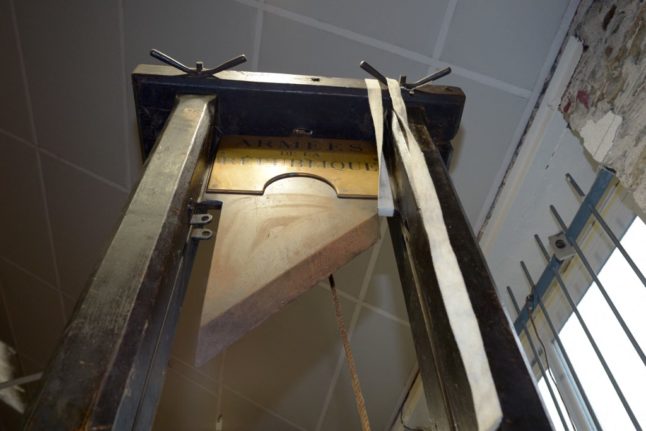

Djandoubi was the last person in France to be executed by guillotine – the first was notorious highwayman Nicolas Jacques Pelletier. Pelletier’s public execution took place at 3.30pm on April 25th, 1792, outside Hôtel de Ville in the Place de Grève.

It was reported that the large crowd – eager to see the device in action – were disappointed that it worked so well and so quickly. It was ‘too clinically effective’ to provide the entertainment the bloodthirsty crowd were expecting. Sections of the crowd, apparently, called for the return of the gallows.

The following year the guillotine claimed perhaps its most famous victim – King Louis XVI, followed nine months later by his wife Marie Antoinette.

Earlier execution methods

Prior to the introduction of the guillotine as the only legal means of execution in France, a number of pretty grim methods of killing convicted criminals were used, including hanging, decapitation by sword (for the nobility only, naturally), burning, the breaking wheel, boiling and dismemberment.

The method of death depended on the crime. Had he been convicted a few years earlier, Pelletier could have been condemned to a particularly brutal death on the breaking wheel.

Adoption of the guillotine

The guillotine was adopted in France as the sole legal form of execution in March 1792, six months after the National Assembly had rejected efforts put forward by the Revolutionaries to abolish the death penalty altogether.

Instead, it decided that Tout condamné à mort aura la tête tranchée (All those condemned to death will have their heads cut off) – in keeping with the Revolutionary ideas of equality there was no longer a ‘special’ method for aristocrats.

The new rule was at the instigation of physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, who had proposed that all executions – regardless of the social status of the convicted person – should be carried out by a simple and painless mechanism.

His proposal – an attempt to make executions more ‘humane’ – included the following six articles:

- All punishments for the same class of crime shall be the same, regardless of the criminal;

- When the death sentence is applied, it will be by decapitation, carried out by machine;

- The family of the guilty party will not suffer any legal discrimination;

- It will be illegal to anyone to reproach the guilty party’s family about his/her punishment;

- And property belonging to the convicted shall not be confiscated;

- The bodies of those executed shall be returned to the family if so requested.

Later, death by firing squad was introduced for crimes ‘against the safety of French State’. Both forms of execution were still on the books until the death penalty was abolished in France in 1981.

What’s in a name

Contrary to popular misconception, Guillotin did not invent the guillotine – nor was he executed by it. He wasn’t even in favour of it, but merely saw making execution humane a step on the road to the abolition of the death penalty.

The device itself was designed by surgeon Antoine Louis, physician to the king, and the prototype was built by German engineer Tobias Schmidt – best known for making harpsichords.

They were inspired by a number of similar devices that had existed, in various forms, for centuries. The Roman Mannaia was an early example; mention is made of a beheading machine in an 11th-century document, while a woodcut illustration of an execution method similar to the guillotine was made in 1532, and a similar device was in use between 1565 and 1710 in Edinburgh.

The key difference, however, between what became recognised as a guillotine and its precursors was the angled shape of the blade.

It was called – for some time after its invention – the louisette, after the doctor who designed it.

The Guillotin family was so embarrassed by the association of their name and the method of execution that they petitioned the French government to rename it. The government refused – so they changed their name.

A doctor in Lyon with a similar name was executed, leading to the incorrect belief that Joseph-Ignace Guillotin was executed by the machine that was named after him. In fact, he died at home, of natural causes, at the age of 75 in 1814. He’s buried at Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris – alongside Jim Morrison, Oscar Wilde, Frederic Chopin, and Marcel Proust.

Could the death penalty be reintroduced in France?

In 2020, some 55 percent of French people supported the reintroduction of the death penalty, according to a poll. To do so would require the country to unilaterally reject several international treaties – not to mention protocols in the European Convention on Human Rights.

In 2002, France and 30 other countries signed Protocol 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights, which forbids the death penalty in any circumstances, even in times of war. The protocol came into effect in July 2003.

Despite the wishes of the mostly hard to far-right of the political spectrum, it is unlikely the death penalty will be reintroduced.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments