Just three years ago, the then proudly anti-establishment Five Star Movement (M5S) won a stunning 33 percent of the vote in a landmark general election win that propelled it into power.

But it currently has no formal leader, is hopelessly divided and is languishing in the polls after several policy U-turns and broken campaign promises.

READ ALSO: How the rebel Five Star Movement joined Italy’s establishment

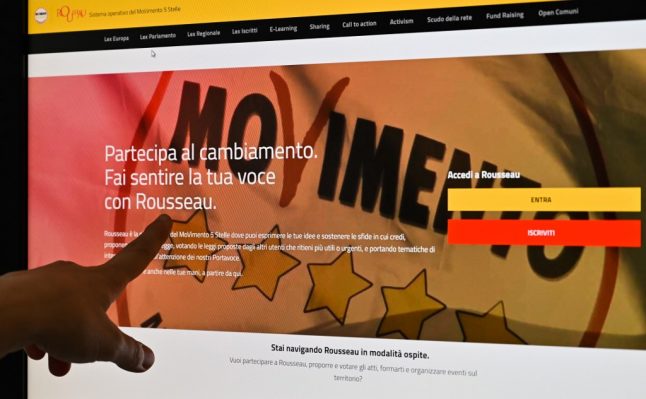

Meanwhile, the party has lost access to its own online voting system, Rousseau, amid leadership in-fighting.

“They are really on the rocks,” commented Piergiorgio Corbetta, an emeritus professor at the University of Bologna who has written extensively about the rise and fall of the M5S.

The movement remains part of Prime Minister Mario Draghi’s ‘national unity’ government and the largest party in parliament.

But between a quarter and a third of its lawmakers have left or have been expelled from its ranks, while it is half as popular as it was in 2018, polling at under 17 percent.

Former premier Giuseppe Conte has been tapped to take over and revive the party, but infighting means his nomination has been blocked.

Five Star’s online voting system, Rousseau, was at the centre of the party’s campaign for “digital democracy”. Photo: Andreas Solaro/AFP

They are now, according to Corbetta, “totally irrelevant” in Draghi’s government, holding just four out of 23 ministerial posts, and politically drifting, with their putative alliance with the centre-left Democratic Party (PD) a work in progress.

“I can’t deny that it is a difficult and tense period,” M5S lawmaker Sergio Battelli told AFP. “The movement has evolved, it has changed, it has made some errors… but the M5S is here to stay.”

Neither left nor right

Comedian Beppe Grillo launched the M5S in 2009 with Gianroberto Casaleggio, an internet guru, by organising rallies against Italy’s deep-rooted problems with political corruption.

They swept up voters outraged at the austerity imposed in the wake of the eurozone debt crisis of 2011-12, which pushed Italy to the brink of insolvency, and followed a radical anti-elites, anti-corporate agenda.

READ ALSO: An introductory guide to the Italian political system

The movement claimed to be neither left- nor right-wing, and vowed never to ally with other political parties.

But they were forced to after the 2018 election, which while historic, left M5S short of a parliamentary majority to govern on its own.

It initially formed a populist, eurosceptic coalition government with the nationalist, anti-immigration far-right League led by Matteo Salvini.

Barely a year later, it switched to a pro-Europe coalition with the PD.

Mirroring that ideological switch, the M5S went from courting an alliance with France’s anti-government “Yellow Vest” movement to seeking ties with French President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist LREM party.

The M5S is now in office with both the League and the PD, as part of the ‘national unity’ government led by Draghi – the former European Central Bank president who saved the euro currency the M5S once reviled.

PROFILE: Who is new Italian prime minister Mario Draghi?

In office, the M5S softened or dropped many of its flagship policies, such as its opposition to high-speed railway projects, which it considered a corruption-prone waste of public money.

But it also scored some results, notably the introduction in 2019 of the reddito di cittadinanza, a form of income support for the unemployed.

Enrico Garitta, a 25-year-old M5S member from Palermo, said the party has effectively grown up.

“Some of the things they were saying, on Europe, for example, were man-on-the-street slogans that didn’t stand up to the realities of governing,” he said.

Even if formally leaderless, the party still has a father figure in Grillo. But he is mired in controversy and accusations of misogyny after publishing a video defending his son Ciro against allegations of gang rape.

Meanwhile, Alessandro Di Battista, once one of its most popular figures,has quit and is rumoured to be considering forming a new party with other rebels, possibly with help of co-founder Casaleggio’s son Davide.

Davide Casaleggio inherited from his father the online platform that formed the M5S’ organisational backbone, and is refusing to hand it over.

The M5S has disowned him, but in the process lost access to its official blog, party membership lists and online voting mechanisms — meaning Conte cannot formally be crowned leader.

Lawmaker Battelli railed against the “mistimed and shameful” episode, adding: “We’re going to have to sort this out in court.”

By AFP’s Alvise Armellini

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

I liked MS5 once but that changed 100% once in government and now i will be pleased to see them vanish forever.

A completely useless party.