During the ensuing 35-year-dictatorship of General Francisco Franco cinema was used as a propaganda machine churning out stories which venerated church, state, and the victory of Franco’s forces over communism.

But in the years since El Caudillo died in 1975, it is a period that has fascinated Spanish and foreign filmmakers, some dramatizing true stories and others using the conflict as a backdrop.

Here is a selection of some of the best films that tell us something about the wrenching upheaval of that wartime period.

Freedomfighters (Libertarias, 1996)

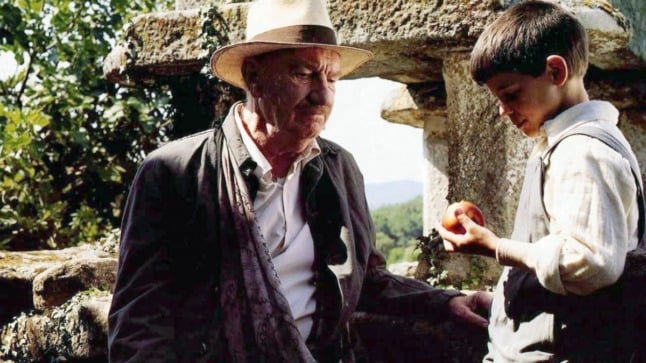

Butterfly Tongue (La Lengua De Las Mariposas, 1999)

Land And Freedom (Tierra y Libertad, 1995)

¡Ay, Carmela! (1990)

The Soldiers of Salamis (Soldados de Salamina, 2003)

There Be Dragons (Encontrarás dragones, 2011)

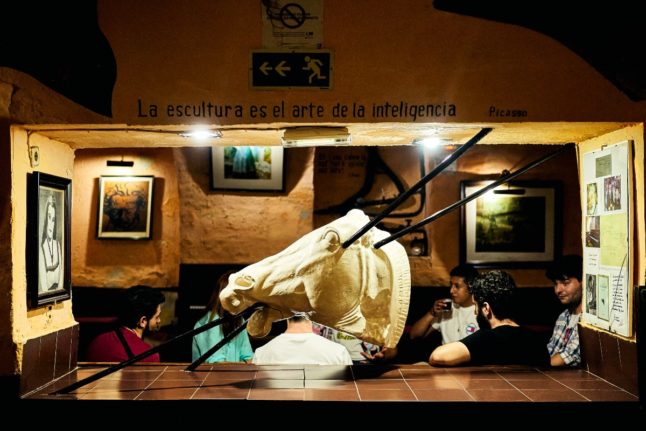

British writer-director Roland Joffé explored themes of faith, friendship, love and betrayal in his story about a journalist investigating a recently canonised priest and discovers his own family’s dark connections with the past.

The Sleeping Voice (La Voz Dormida, 2011)

Based on the novel by Dulce Chacón, which won the 2003 Spanish Book of the Year.

Belle Epoque (1993)

The Heifer (La Vaquilla, 1985)

The 13 Roses (Las 13 Rosas, 2007)

While the War Lasts (Mientras Dure la Guerra, 2019)

Acclaimed director Alejandro Amenábar is behind this portrait of the Civil War seen from the perspective of one of the greatest Spanish writers of his time, Miguel de Unamuno, who controversially supported the military coup.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Can you advise on where these movies can be viewed? Are they on any streaming platforms?