Despite having a job and refugee status, he was ordered on to the vehicle.

“We didn’t have any choice,” he explained.

Along with others scooped up at the disaffected office building, he was told he was being sent by bus to Toulouse — a nearly 700-kilometre (435-mile) trip of seven or eight hours to the southwest.

“They (the police) went from room to room to tell us to get out, then they took our identity documents and said ‘get in the bus’,” he added in an

interview with AFP. “It was impossible to get out of it. They were saying we had to hurry up.”

Ali, who has a job as a cleaner at Disneyland Paris earning 1,400 euros ($1,500) a month, had been caught up in the French government’s policy of sending migrants from the capital to regional towns.

It was announced by French President Emmanuel Macron in September 2022 during a speech in which he criticised the idea of concentrating refugees and migrants in low-income and troubled neighbourhoods of Paris as “absurd”.

READ ALSO: France’s allies to help with Olympics security

Rather than adding strain to the stretched social services of these areas, he argued that asylum seekers and refugees could help reverse declining populations and labour shortages in other areas of the country.

Some charities welcomed the idea in principle, but worried about the implementation.

It caused immediate fury among anti-immigration politicians, and many charities now suspect Macron and his ministers of wanting to clean up Paris ahead of the Olympic Games this July and August — which the government denies.

‘Not our problem’

Ali’s experience demonstrates the difficulties of relocating people.

He didn’t know Toulouse and, once he arrived there, he was taken to an asylum seekers’ centre where he was told he couldn’t stay for longer than four days.

Because he had already obtained refugee status, he was also informed that he shouldn’t be there “along with 17 other refugees” who had been transported from Paris, he remembers.

“I explained that I didn’t know where to go and that I didn’t know anyone.

They told me ‘it’s not our problem’,” he explained from his new home, an office building in Vitry-sur-Seine in southeast Paris occupied by 400

migrants.

Soon after arriving in the southwest, he bought a return ticket to Paris and managed to save his job at Disneyland.

Abdallah Kader, a 51-year-old from Chad in northern Africa, was another person evacuated from Ali’s squat on the Ile-Saint-Denis, an area of Paris that will host the Olympic village during the Games.

Also with refugee status, he was sent to Bordeaux in southwest France, but decided to return to the capital soon after.

“I know people here. We help each other. I find work,” he said in Vitry-sur-Seine where he sleeps in a small former office with another refugee.

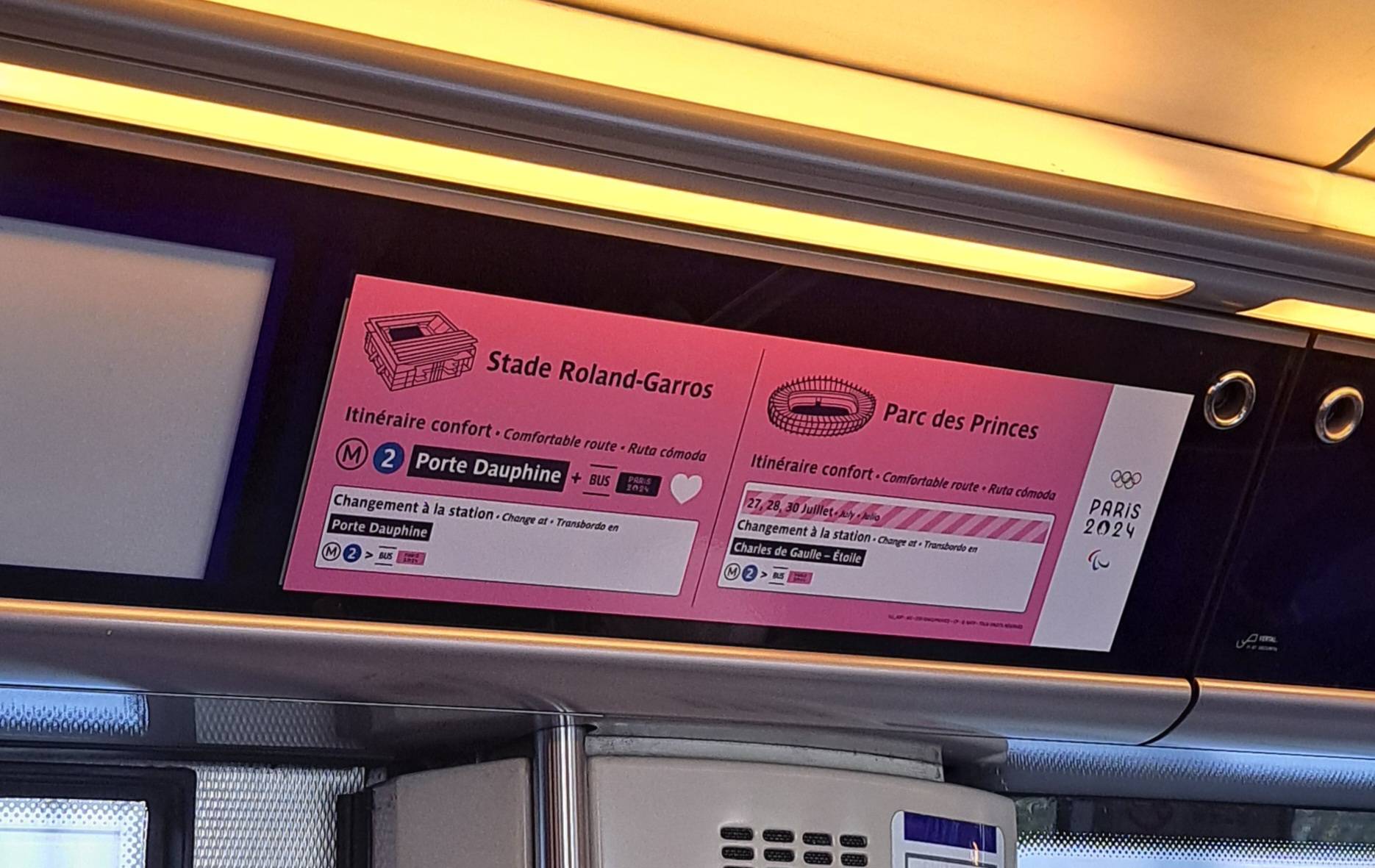

READ ALSO: Paris Olympics Guide: How Metro tickets, passes and apps work

‘Social cleansing’?

Abdallah was once employed as a security guard at one of the many building sites around Paris linked to the Olympic Games which kick off on July 26.

Several charities are convinced that the migrant transfers are linked to a desire among French authorities to banish rough-sleeping, tents and squats from the capital before the eyes of the world fall on its famed cobbled streets.

In February, an umbrella group of 80 French NGOs denounced what it called the “social cleansing” of Paris ahead of the Olympics with efforts to remove migrants, the homeless and sex workers.

“Clearly ahead of the Olympics, there are transfers, a social clean-up to prepare the city for the arrival of tourists,” Jhila Prentis, a volunteer at

United Migrants, a charity that works in Vitry-sur-Seine.

The group wants the state to run more checks before sending people to provincial France “so that it meets their needs and that they agree to leave,” she added, explaining that often “they have a life here.”

France logged 167,000 requests for asylum last year and Macron is under constant pressure from right-wing political opponents and public opinion to reduce immigration.

Housing Minister Guillaume Kasbarian told parliament on Tuesday that 200,000 homeless people slept each night in shelters provided by the French state, with 100,000 of these places in the capital region.

“Given the saturation in the Paris region, not everyone can find a place,” he added. “That’s why, without any link to the Olympic Games, the government put in place a dispersal policy from March 2023,” he explained.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments