Norway’s streets and squares have stories to tell, with many of their names paying homage to the Norwegians of centuries past.

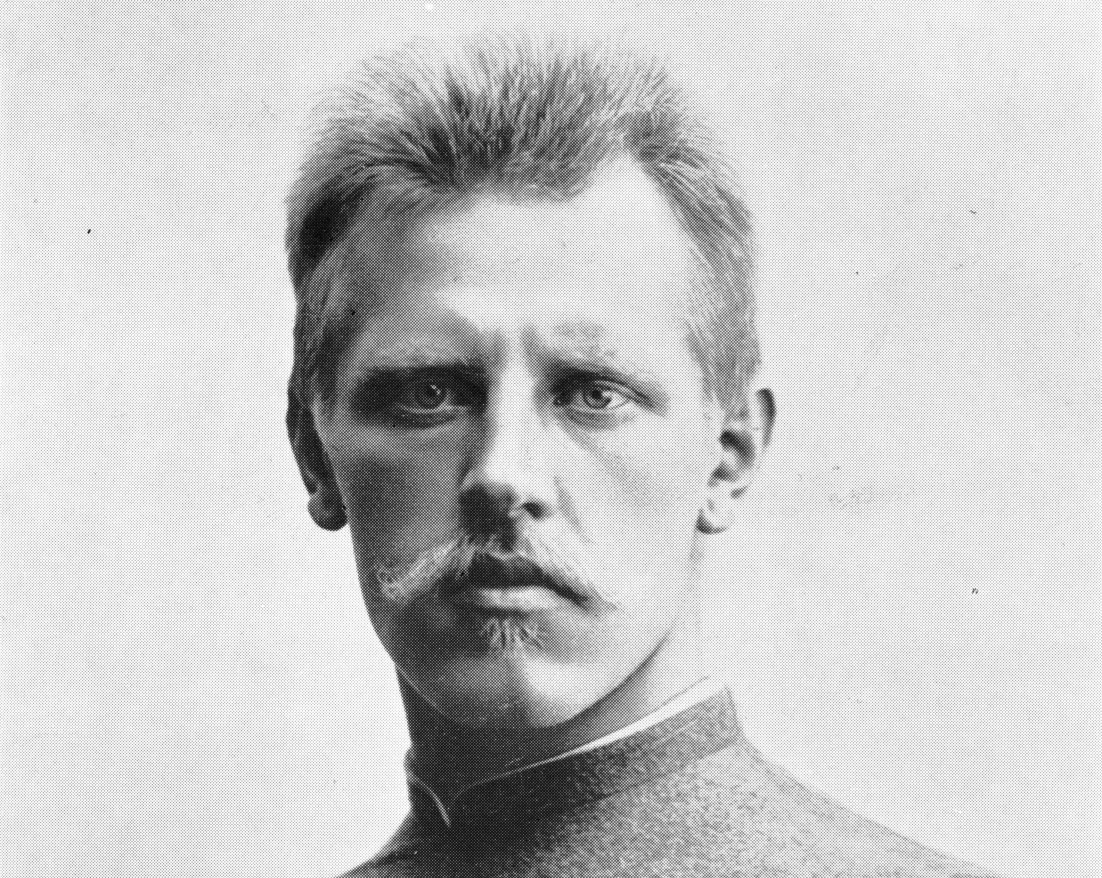

Haakon VII

As the first king Norway had after regaining its independence from Sweden in 1905, it is perhaps unsurprising that Haakon VII has given his name to central streets in Oslo, Trondheim, Bergen, Stavanger, and many other towns and cities in Norway.

Born Prince Carl of Denmark in 1872, he took the Old Norse name Haakon on accession to the throne as the first independent Norwegian monarch since 1387.

After the conquest of Norway by Nazi Germany in 1940, Haakon went into exile in the UK, refusing to give his backing to the puppet government led by Vidkun Quisling.

He then became the figurehead for the Norwegian resistance, meaning he was greeted as a national hero when he returned to Norway after the country was liberated in 1945.

Kristian IV

Kristian IVs gate, leading from Oslo Cathedral and alongside Karl Johan gate, is one of the main streets in Oslo.

The street is named after Christian IV, the 17th century King of Denmark and Norway, who laid the foundations for much of modern Oslo after the old city was gutted by a fire in 1628, with the new city named Christiania in his honour.

There’s another Kristian IVs gate in Kristiansand, which also named after this great city builder, as are the Copenhagen district of Christiania and the Swedish city of Kristianstad.

Kristian IVs reign saw Denmark-Norway eclipsed by Sweden, with the country enduring a succession of military defeats. Despite this his reign is still seen in Denmark as a golden age.

Fridtjof Nansen

The square surrounding Oslo City Hall is called Fridtjof Nansens plass (plass meaning square or place in Norwegian), commemorating Norway’s most famous explorer and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.

As soon as Fridtjof Nansen completed his doctorate in marine zoology, he set off on his first major Arctic exploration voyage, crossing Greenland’s interior in 1888 on cross-country skis. He followed this up with his Fram expedition, which fell short of reaching the North Pole, as he had hoped, but did reach a record northern latitude of 86°14′.

There’s a Fridtjof Nansens vei (vei meaning road in Norwegian) in Trondheim, but apparently no road commemorating this great explorer in Bergen.

Roald Amundsen

Fittingly, Fridtjof Nansens plass in Oslo leads directly onto Roald Amundsens gate, just as Nansen’s Arctic exploits inspired Roald Amundsen in his own exploits.

Amundsen was famously the first person to reach the South Pole, beating the ill-fated British expedition led by Captain Robert Scott.

Amundsen has a claim to be the first to reach the North Pole as well, as the two other expeditions which make the claim, led by Robert Peary, a US Navy admiral, and Frederik Cook, are both disputed. Amundsen did, however, travel by airship, which some might say was cheating.

You can also find a Roald Amundsens gate in Trondheim, Sandnes and Sarpsborg.

Olav V

Like his father, King Haakon VII, Olav V was born a Danish prince with another, much more Danish name. Alexander Edward Christian Frederik, Prince of Denmark, was born at Appleton House, on the grounds of the UK’s Sandringham Palace, where his British mother, Princess Maud of Wales, was staying courtesy of her father, King Edward VII.

When Haakon VII was made King of Norway in 1905, his son moved to Norway with him, taking the more Norwegian name, Prince Olav. He became King Olav on the death of his father in 1958.

You can find streets named Olav Vs gate in Oslo, Stavanger, Bodø, and Vikhammer, but not – as often seems to be the case – in Bergen.

Johan Herman Wessel

While he is relatively unknown outside Norway, the poet and writer Johan Herman Wessel, who was born in Norway but died in Copenhagen, was one of the leading figures of The Enlightenment in Denmark-Norway, winning renown for his collection of comic stories and the play Kjærlighet uden strømper, or “Love without Stockings”.

There’s a Wessels plass in Oslo, a Wessels gate in Trondheim and a Wessels vei in Stjørdal.

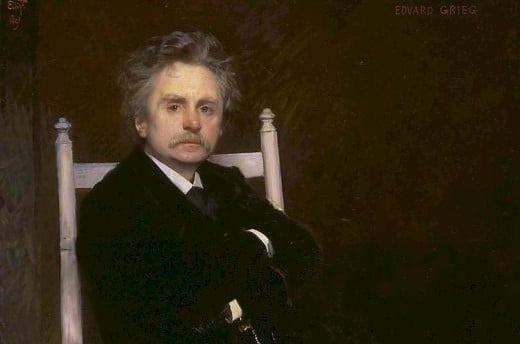

Edvard Grieg

Edvard Grieg, the 19th-century composer, is very much known outside Norway, and he is commemorated with streets in Oslo, Bergen and Trondheim, although few of them are central, perhaps because he made his name after the city centres had already been built.

Grieg’s most famous works are probably his lyrical piano pieces or perhaps the incidental music he composed for Henrik Ibsen’s play Peer Gynt.

Henrik Ibsen

The playwright Henrik Ibsen is arguably more famous internationally even than Grieg, and he gives his name to Henrik Ibsens gate in Oslo and also to other streets of the same name in Bergen, Drammen and Frederiksberg.

Remarkably for an author from a relatively small country, Ibsen is the most frequently performed dramatist in the world after Shakespeare, with A Doll’s House, his most famous play, holding the title of the world’s most performed play (a few years ago, anyway).

Ibsen was born in 1828 in Skien and died in 1906 in Oslo.

Marcus Gjøe Rosenkrantz

It’s hard not to think that the Rosencrantz gate you can find in Oslo, Bergen, Stavanger and elsewhere refers to the character in Shakespeare’s Hamlet or that they refer to some other renowned Rosenkrantz.

In fact, these streets commemorate the politician Marcus Gjøe Rosenkrantz (1762-1838), the Norway-born civil servant and politician who served as Norway’s prime minister between 1814 and 1815 and was a leading figure at the meeting in Eidsvoll where the Norwegian constitution was drawn up in 1814.

He was a member of the Rosenkrantz family, part of the Danish nobility, with branches in Norway and Sweden.

Coincidently, Eidsvolls plass is a square and park just in front of the Storting, or Norwegian parliament, in Oslo

Professor J.C. Dahl

You will find Professor Dahls gate leading down to Frogner Park in Oslo, but you’ll also find the name in Bergen and Sandnes.

Rather than commemorating a scientist or academic, these streets, in fact, celebrate the man credited with putting Norwegian fine art on the map.

Johan Christian Clausen Dahl, or just JC Dahl, was a 19th-century painter considered the first person from Norway to reach the level of artists from the continent. As a student, Dahl lived in Dresden with the more renowned German romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich.

On his return to Norway, he helped found Norway’s National Romantic art movement, capturing the country’s dramatic landscapes in oil.

Peter Andreas Munch

Given that Edvard Munch is a far more famous painter than Dahl, it’s surprising that there are no streets named after him in Norway (as far as we can see).

There is a Munchs gate in Oslo, which is named after his uncle, Peter Andreas Munch, as is PA Munchs gate in Trondheim.

Peter Andreas Munch (1810-1863) was a Norwegian historian known primarily for his history of Norway, Det norske Folks Historie.

Johan Nordahl Brun

You can find a Nordahl Bruns gate in Oslo, Bergen, Lillestrøm and Drammen, and a Nordahl Bruns vei in Trondheim.

Johan Nordahl Brun, 1745-1816, was a theologian, writer, and songwriter who also became Bishop of Bergen. Brun wrote Bergenssangen or Nystemte, the city’s anthem. He wrote several plays, and several popular hymns that were included in the Danish Psalmebog for Kirke og Hjem and are still sung in Norway.

Christian C.A. Lange

Langes gate crosses Nordahl Bruns gate in Oslo, and you can also find streets of the same name in Bergen, Drammen, Lillehammer and Sandefjord.

Christian C.A. Lange was a 19th-century Danish-Norwegian historian and archivist who established the Diplomatarium Norvegicum, which collects together all the documents and letters known to have been produced in Norway before 1590. He was also the impetus behind the Norske rigs-registranter, which brought together the texts of laws made by the Danish-Norwegian kings between 1523 and 1660 and the Encyclopedia of Norwegian Authors, 1814-1856.

Oscar I

There’s a Kong Oscars gate in Bergen, and an Oscars gate in Oslo, Skien, Stavanger, and Kongsvinger, all of which are named after Oscar I, who was King of Norway and Sweden between 1844 and 1859.

Oscar was the only son of King Karl III Johan, the Napoleonic general who started Sweden’s ruling Bernadotte dynasty.

Despite a general Norwegian antipathy to the union between Sweden and Norway, Oscar did a lot during his reign to make the union more popular, taking efforts to bolster Norwegian identity, such as giving Norway its own war flag, and creating the Order of St Olaf, the first Norwegian order.

Karl III Johan

Given that Karl III Johan, the founder of Sweden’s Bernadotte dynasty, is a far more significant monarch than his son, it’s odd that, so far as we can see, Oslo, Sarpsborg and Halden are the only Norwegian cities to have a Karl Johans gate. In Bergen and Trondheim he remains commemorated.

Karl Johans gate is, however, one of Oslo’s most central streets, however, leading from parliament to the Royal Palace.

Karl XIV Johan, as he’s known in Sweden, was born Jean Bernadotte to a stolidly middle-class family in Pau, France, and rose to become one of Napoleon Bonaparte’s top generals.

When Crown Prince Karl August, the only son of Sweden’s King Charles XIII, died suddenly in 1810, he was persuaded to anoint Bernadotte as his new Crown Prince, and when he died in 1818, Bernadotte became King of Sweden and Norway, founding the Bernadotte dynasty.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments