What’s going on?

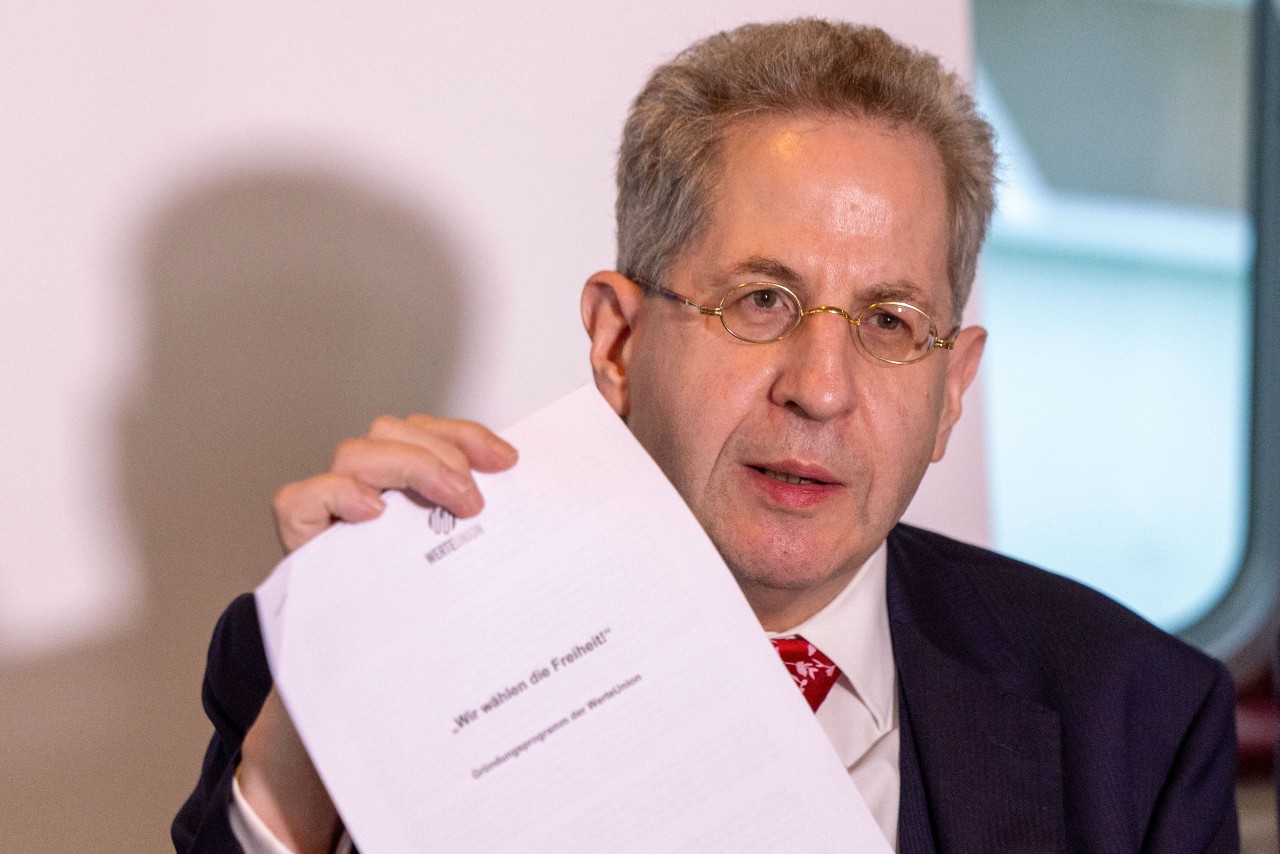

It was an unconventional start to the founding of a new party: huddled on a boat on the Rhine somewhere near Bonn, the founding members of the new WerteUnion (Union of Values) party signed the official founding act and unanimously elected their new leader: former CDU politican Hans-Georg Maaßen.

The whole meeting was done in private – almost in secret – with no members of the public in attendance. Even the planned location of the boat was changed at the last moment, presumably to avoid protestors. Almost everything about the meeting felt designed to slip under the radar. But it didn’t.

That may be because, far from being an unknown quantity, the WerteUnion is already well-known in German political circles – as is its controversial leader.

Though the party may be small, it’s impact on the German political landscape could be tumultuous.

What is the WerteUnion?

The new party grew out of a registered association by the same name, which was roughly – though not officially – affiliated with the conservative CDU and CSU.

Founded in 2017 while Angela Merkel was still chancellor, the previous incarnation of the WerteUnion acted both as a pressure group that aimed to push the CDU further the right and also as a home for disgruntled CDU members who longed to see more conservative stances on everything from climate politics to the handling of refugees.

In its party form, it may well play a similar role: Maaßen is pitching ‘taster’ memberships to CDU and CSU members that allow them to get involved with the WerteUnion for a year without forfeiting their CDU or CSU membership.

But wait, another new party?

That’s right. Following the founding of former Left Party politician Sahra Wagenknecht’s new party, the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), yet another new party has entered the political fray this year.

For anyone unfamiliar with Wagenknecht and her party, it can best be described as a socially conservative and economically left-wing party, combining progressive taxation policies with a heavily migrant-sceptic and “anti-woke” stance.

Wagenknecht herself is an outspoken Left Party veteran who in the past few years has increasingly become a thorn in the side of her former party, heavily criticising their policies on migration and climate protection, among other things. Most controversially, she has been accused of maintaining close links to Russia and of parroting Kremlin lines on issues like Russian gas deliveries and the war in Ukraine.

READ ALSO: Why is a German populist left leader launching a new political party?

The splintering off of Wagenknecht and nine other defectors ultimately led to the collapse of the Left Party as a parliamentary party, meaning the 28 remaining MPs can now only describe themselves as a “group”. It’s possible that Maaßen intends to splinter the CDU in a similar way, though the CDU and CSU are significantly stronger as a parliamentary force, with hundreds of MPs currently in the Bundestag.

The similarities between Wagenknecht and Maaßen’s parties go further than that, though: both are heavily critical of the current government’s asylum and migration policies, have slammed the so-called “woke agenda” on issues like gender and racial equality and say climate protection measures are too expensive. However, unlike the Wagenknecht Alliance, the WerteUnion is in favour of hard-right economic policies that could best be described as libertarian.

So what does the WerteUnion actually stand for?

Placed on the political spectrum, the WerteUnion can be placed somewhere between the conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD).

In fact, leader Maaßen has said he wants to fill a “gap” in German politics between the CDU, which is too moderate, and the AfD, which is too extreme.

“We stand for classic civic values that have made Germany strong and that ultimately shaped the CDU,” Maaßen said, adding that the party was in favour of freedom, the rule of law, democracy and tolerance, but also in favour of the state withdrawing from people’s lives.

This last point seems to be the most significant one: the WerteUnion is vehemently against Green policies such as the transition to eco-friendly heating and electronic vehicles. They are vociferous opponents of inclusionary policies such a gender-neutral language and say that children should be “protected from early sexulisation and gender ideology” in schools and Kitas.

On immigration, they are in favour of a tightening of citizenship rules to prevent foreigners becoming German “too quickly”. According to the party programme, the skilled worker shortage should be combatted with domestic policies rather than immigration, though some skilled immigration is permitted “to a limited extent”.

Ultimately, however, they are in favour of more heavily policed borders and tight controls on immigration.

In the opening section of its programme, the party states that it rejects “totalitarian world views” and “radicalism”. However, unlike almost all other parties in German politics, the WerteUnion is open to working with the far-right AfD and members were said to be present last November at a meeting of extremists that was investigated by Correctiv this year.

READ ALSO: Germany’s far-right AfD denies plan to expel ‘non-assimilated foreigners’

Questions may also be asked about whether the party’s leader, Hans-Georg Maaßen, also holds more extreme views than the party’s programme suggests.

Why is Hans-Georg Maaßen such a controversial figure?

Formerly a CDU member, Maaßen left the party at the end of January this year after numerous attempts to eject him had failed.

Since July 2021, the conservative leadership had been trying to distance themselves from the WerteUnion founder over his perceived extremist views. This culminated in a motion from the CDU executive committee unanimously calling on Maaßen to exit the party, followed by official expulsion proceedings when the right-wing politician let the deadline for resigning pass.

In their motion, the executive committee noted that Maaßen regularly used “language from the milieu of anti-Semites and conspiracy theorists through to ethno-nationalist expressions” and had continuously violated the principles of the party.

With a background in law, the leader of the WerteUnion is best known for his stint as President of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BVS). According to reports in Spiegel, Maaßen allegedly slammed the breaks on an investigation into the AfD during his tenure there, and is also accused of advising the far-right party directly on how not to attract the authorities’ attention.

He has since revealed that his previous employer, the BVS, has flagged him as a potential right-wing extremist.

In tweets, he has claimed that the media is involved in an “eliminatory campaign of racism against whites”. These comments prompted the director of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp Memorial, Jens-Christian Wagner, to accuse Maaßen of a “classic right-wing extremist reversal of guilt” and trivialising the Holocaust.

But can the WerteUnion actually win anything?

That remains to be seen. So far, the party has said it will not stand in the EU elections in June but will stand in the three state elections this year in Thuringia, Saxony and Brandenburg.

These three eastern German states are all AfD strongholds where it may well be possible for Maaßen’s party to split the right-wing vote and potentially act as a challenger to Wagenknecht’s BSW.

READ ALSO: Analysis – Are far-right sentiments growing in eastern Germany?

With disillusionment over the current centre-left coalition of the Social Democrats (SPD), Greens and Free Democrats (FDP) on the rise, right-wing parties have been climbing the polls lately, with the latest figures putting the CDU and CSU on 34 percent while the AfD hovers around the 20 percent mark.

Though there are still no polling figures to forecast how many votes the WerteUnion could win in the state elections, however, political scientists say the party could struggle to carve out its own niche among its competitors.

According to Benjamen Höhne, a researcher at Trier University, there is currently no need for Maaßen’s new party in the political spectrum. “The CDU/CSU, the Free Voters and the AfD are already there,” he told watson.de.

That said, the launch of the party is well-timed for the WerteUnion to act as a potential coalition party to the AfD in lieu of other political support – and could make it harder for other parties to form governing coalitions if the vote is splintered.

Most significantly, though, the entrance of the new party on Germany’s political scene represents a further lurch to a right at a time when anti-migrant politics appear to be gaining ground.

READ ALSO: Could the far-right AfD ever take power in Germany?

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments