The multicoloured “violins of the sea” were made by prisoners out of rickety boats washed up on the small Italian island of Lampedusa, a first port for many seeking to cross from North Africa.

The debut of the “Orchestra of the Sea” with the instruments, formed especially for the occasion, visibly moved the audience.

Two of the violin makers – inmates from the high security Opera prison near Milan – watched Monday’s performance of Bach and Vivaldi from the theatre’s royal box, usually reserved for state dignitaries.

“To be invited to La Scala for something we created is magic” said 42-year-old Claudio, one of the prison’s four apprentice luthiers who is serving a life sentence for two murders.

Cracked and diesel-soaked wood from the migrants’ boats, destined for the scrapyard, was transformed into the violins, violas and cellos.

‘Giving waste a voice’

“We give voice to everything that is usually thrown away: the wood from boats that is shredded, the migrants who flee war and poverty and are treated like trash, and the prisoners who are not given a second chance,” says Arnoldo Mosca Mondadori, who came up with the idea.

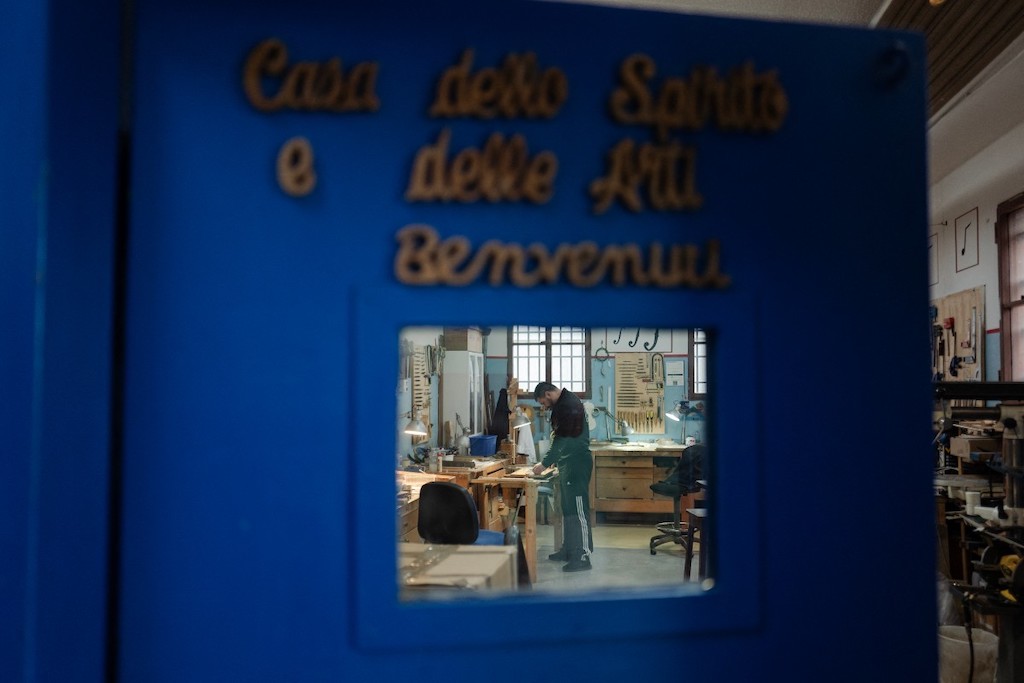

Mosca Mondadori, president of the House of the Spirits and the Arts foundation, hopes the string instruments can be played in other concert halls in Europe, “to touch people’s souls in the face of poverty”.

READ ALSO: Italy’s Lampedusa struggles as migrant arrivals double the population

The central Mediterranean is the deadliest migratory route in the world. Nearly 2,498 people died or disappeared along it last year, some 75 percent more than in 2022.

In a courtyard at the Opera prison, dilapidated boats are strewn across the grass among broken planks of wood.

A pink and white baby shoe, a baby bottle, nappies and a tiny green T-shirt are among items recovered from their holds.

Discarded clothing stiff with salt, rusting cans of sardines, and rudimentary life jackets evoke perilous journeys at the mercy of rough seas. “You can smell the sea here,” within the grey concrete walls of the courtyard, 49-year-old prisoner Andrea said.

“It is very strong and transports you very far. It is present even in the instruments, though less so,” he says as he dismantles boats and searches for suitable wood to make the instruments.

‘Alive and useful’

Andrea, who is serving a life term for murder, sees the time he spends in the wood workshop as a form of “redemption”.

“Time does not pass in prison. But there, we feel alive and useful,” he said.

In the small dark room with barred windows, Nicolae, a 41-year-old Romanian behind bars since 2013, is busy sawing a piece of wood.

He takes measurements, before carefully carving a violin’s soundboard.

READ ALSO: EXPLAINED: What’s behind Italy’s soaring number of migrant arrivals?

“By building violins… I feel reborn,” he said.

Paring tools, penknives, chisels, saws and small wood planes are lined up on a wall panel, potential weapons which are scrupulously checked back in at the end of the day by the guards.

Standing in front of his workbench, master luthier Enrico Allorto says that he used a method from the 16th century when bending the wood, in order to keep the boat varnish intact.

There is no Stradivarius here. These violins have “a more muted timbre, but they have their charm and reproduce the entire range of sounds”, he says.

“They arouse emotions in the musicians, who in turn transmit them to the public”.

By AFP’s Brigitte HAGEMANN

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments