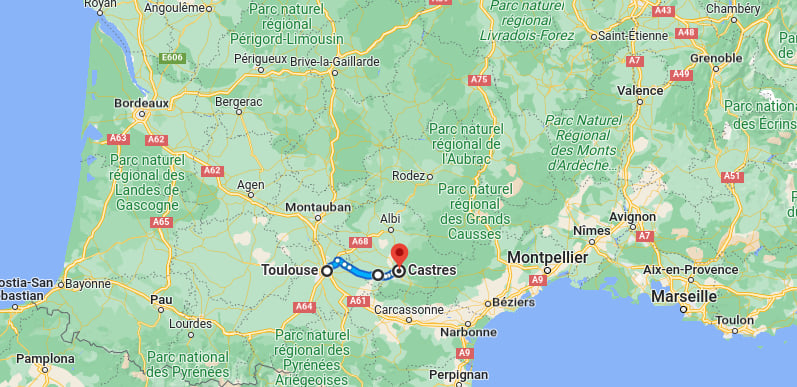

Where is this new motorway?

Work on the A69, a 53km motorway connecting the south-western town of Castres and the city of Toulouse, has already begun.

The two places are just 77km apart, but at present driving along the winding, single-lane road takes around 1 hour 20 minutes.

The proposed A69 motorway, if completed, will cut between 15 and 35 minutes from the journey time.

Why is it being built?

The government line on the building of new roads – and the A69 specifically – is that they are essential to improving lives in areas of rural France by better connecting them to the rest of the country.

“We must listen to the demands of the population on the questions of improving access,” said Environment Minister Agnès Pannier-Runacher in an interview on RMC earlier this year. “Lots of people in rural territories think we do not take care of them. They do not have the same access to public services, they cannot live as easily as people who live in Paris for example,” she said.

Local officials and business leaders in the region have also argued that the construction is necessary and will boost economic growth.

The A69 construction has faced more than 10 legal challenges, all of which have been struck down. The government says that given the construction has been approved by MPs democratically elected by the people, it should continue to go ahead despite criticism. It also argues that given construction has already begun, it doesn’t make sense to stop.

It says it will plant new trees to offset the carbon emissions and deforestation caused by the construction of the road.

Why are some people against it?

The principal opponents to the A69 construction are environmentalists, some of whom have staged huge protests this year.

The most prominent protest figure is Thomas Brail, an activist who spent weeks on hunger strike on top of a tree outside the Environment Ministry.

After Brail met the 40-day milestone for his hunger strike, construction on the motorway was paused for one week.

Last Tuesday, Brail, and two other activists, called off their hunger (and thirst strike).

Some 200 trees will need to be cut down to make space for the new road and 316 hectares of will be decimated if the project is completed.

There is already a train line connecting Toulouse and Castres which emits three times less CO2 than the existing road route. “This would be 25 times less emitting if the train line, which is currently runs of diesel, was electrified,” according to an open letter published by 200 scientists opposed to the A69 over the weekend.

“This project contradicts our national commitments to the fight against climate change and to our net zero targets on ‘artificialization’ and biodiversity loss,” they wrote.

The scientists also blasted the government’s proposed carbon offsetting scheme, noting that young trees cannot absorb the same level of carbon as old ones.

Others are opposed to the project for non-environmental reasons, including residents of Teulat – a town of 530 residents set to be cut in half by the new motorway. The mayor of Teulat has been fighting against the project for the past decade and told RMC: “This is a useless project imposed on our population. Our citizens do not feel listened to.”

Are there other controversial motorway projects in France?

France has a number of other ongoing or impending motorway constructions including: an extension to the A104 around Paris; an extension to the A154 connecting Rouen and Orléans; the construction of the A120 in central France and handful other approved projects.

Some 20 further developments have been submitted for approval. France currently lays between 20,000 to 30,000 hectares of concrete every year, mostly for road construction.

But the proposed A69 motorway has drawn the most controversy.

What happens next?

After week-long break, local authorities announced construction had started up again on October 16th.

“We must push forward,” said Transport Minister Clément Beaune when pressed on the question of the A69 on France Inter in early October. He conceded however that other road projects will be halted.

“We will take courageous decisions to stop many projects because we need to be coherent. When dealing with the ecological crisis, we cannot do like before. We have already cut road construction in half and we will continue this effort, building more train lines and less roads,” he said.

In recent years public pressure has helped sink road construction projects like the A45 linking Lyon and Saint Etienne as well as the A147 between Limoges and Poitiers, which means the fate of the A69 might not be settled just yet.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments