Flamenco roots

Growing up on the outskirts of Barcelona, Rosalía Vila Tobella studied at the Catalonia College of Music, which accepts only one student per year into its flamenco programme.

This was the sound of her first album, 2017’s stripped-back “Los Angeles”, featuring Rosalía singing alone with a guitar.

It won many admirers for its new approach to a beloved genre — as well as some conservative detractors — but few predicted the crossover success to come.

Crossover

While studying flamenco, Rosalía was listening to reggaeton with her friends and David Bowie with her mother.

The pop influences crept into her second album, “El Mal Querer” (The Bad Loving), which included a reworking of Justin Timberlake’s “Cry Me a River”.

“You can sense the flamenco tradition, but it’s a whole new thing,” she said at the time.

It was a sensation, winning a Latin Grammy for album of the year, and the lead song “Malamente” racked up 160 million views on YouTube.

The album tracks a toxic relationship, but also makes references as varied as poet Federico García Lorca (killed during Spain’s civil war), flamenco legend Camaron de la Isla and a famous sex club in Barcelona.

Collaborations

The collision of sounds won her an eclectic set of celebrity fans, from brash rap stars like Cardi B and pop stars like Lorde to elder statesmen of indie rock like Michael Stipe and David Byrne.

Rosalía embraced the opportunities, collaborating with some of the biggest names in reggaeton and hip-hop, including Ozuna, J Balvin and The Weeknd.

Her duet with Travis Scott on “TKN” was a huge crossover hit with 218 million views on YouTube.

Reinvention

Rosalía took another bold step with “Motomami”, released in March, delving further into contemporary urban and electro.

It has catapulted her to the very top of the music game, becoming the first album by a Spanish woman artist to reach one billion streams on Spotify, and again winning album of the year at the Latin Grammys.

Its central image of the butterfly was a nod to her own transformations.

“I’m constantly seeing this phenomenon I keep being surprised by, of women and their talent in these predetermined categories: the sexy one, the crazy one, the bossy one, the diva,” she told Rolling Stone.

“But those categories don’t lead anywhere, they’re just limiting.”

.@rosalia made one of 2022's best albums in #Motomami 🏎️ — now she graces our January cover.

Read about how she became one of pop's most unconventional superstars by doing everything her way.

Story/Photos: https://t.co/qt491eiHhn pic.twitter.com/zKMOAXDTIZ

— Rolling Stone (@RollingStone) December 13, 2022

Image

Rosalía has always taken extreme care over her style, which is managed by her sister Pili.

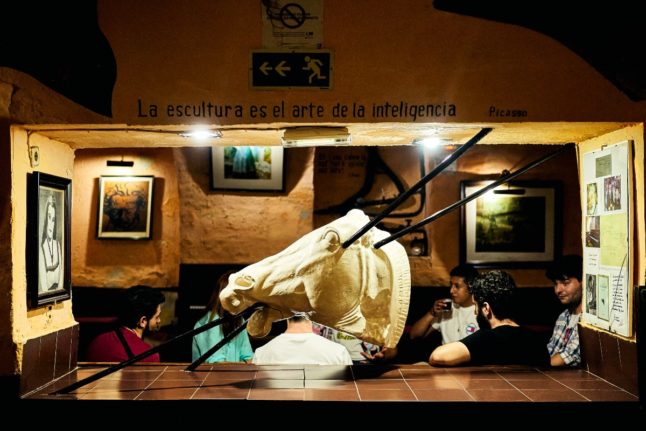

Her videos often have strong Spanish influences, from bullfighting with a motorbike in the clip for “Malamente” to the visuals for “Di Mi Nombre” which drew inspiration from 18th-century painter Goya.

The bold colours of filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar have been another frequent touchstone, and she made an appearance in his last feature “Pain and Glory” in 2019.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments