What a difference a Scholz makes

One of the biggest stories of German politics in recent years has been the decline of the Social Democrats. So why have they appeared to pull themselves together this time around?

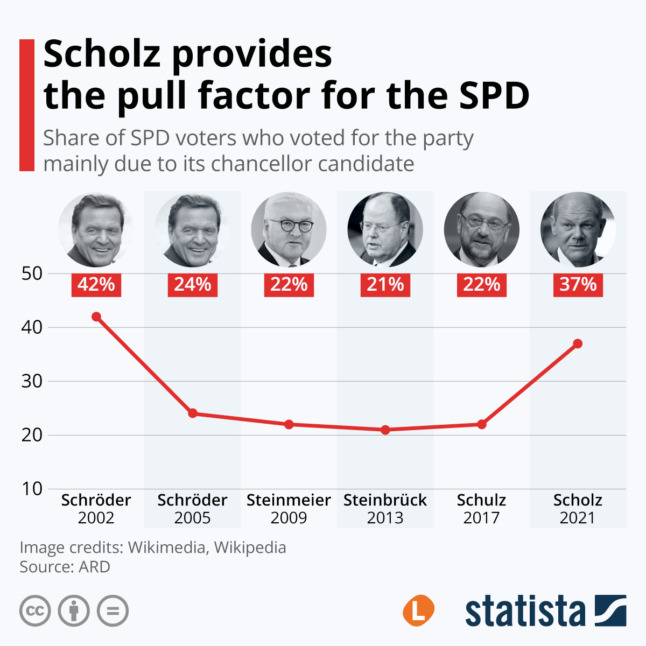

Well, one big factor is who they chose as their chancellor candidate: Olaf Scholz. According to ARD data (shown in this graph below by Statista), only Gerhard Schröder had a higher so-called candidate factor this century compared to Scholz.

That was in the 2002 Bundestag election, but Schröder, as the incumbent chancellor, had the bonus of already being in office.

About 37 percent of SPD voters plumped for the centre-left party due to Herr Scholz, known for being a bit boring but reliable, and offering that stable, Merkel-like brand of calm that Germans seem to love so much.

“The party benefited from the positive image of Olaf Scholz,” political scientist Dr Gero Neugebauer of the Free University in Berlin told The Local.

“If you look at the campaign, it was focused on Scholz. He was the one, he was the well experienced administrator. A man who said: ‘you can trust me, I’m reliable, I’m confident, I am trying to solve problems not only at home but in the world.'”

Another important point: Scholz benefitted from his candidates tripping up.

While the CDU’s Armin Laschet will never live down being caught on camera laughing during a speech at the flooding disaster zone, and the Greens’ Annalena Baerbock grappled with plagiarism scandals, Scholz sat back. And then stepped forward when the time was right. His image was so water-tight much that even a potential financial scandal couldn’t affect his poll ratings, leading Politico to brand him ‘the Teflon candidate’.

“He won some credit ahead of his rivals,” said Neugebauer. “He was a candidate with a far better image than his party. More and more people said – if there’s a positive image of Scholz, why shouldn’t we think that the party has the same possibilities? The benefit came from Scholz.”

But it’s not that great a result for the SPD

Although the SPD has won the election by a whisker, the decline of the Social Democrats’ base support has been happening for years.

Neugebauer says the Social Democrats will still need to address their own internal problems and that the decline in the party will continue – unless it can sort itself out for the future.

The party has been plagued by infighting between centrists and left wingers after years of coalitions with the conservatives.

“There’s a lot of work to do,” Neugebauer said.

READ MORE: How the SPD bounced back to win the German vote

… and it’s a disaster for the CDU/CSU

The vote shares of the former mainstream parties – the centre-right CDU/CSU and the centre-left SPD – in federal elections are at a historically low level – despite gains for the SPD, as shown below in this graph by Statista (the 2021 election results are at the top).

Together, the former Volksparteien reached only about half of all voters in the current election, with 49.8 percent of the vote.

In 1990, their combined share was 77.3 percent of the vote.

Experts interpret the declining power of the major parties as an expression of people’s changing values, lifestyles and diverse world views, reports Statista.

So it’s much a more fragmented picture. And it’s something that Angela Merkel’s conservatives are now having to face head on.

“It’s a complete disaster (for the CDU/CSU),” said Neugebauer. “They have lost about 9 percent of the vote (compared to 2017). They have lost mandates, they have lost the power. The problem is that they didn’t learn within the last two years that the image they give out is not attractive enough so that voters feel they can trust the party and the candidate.”

Neugebauer said voters in Germany believe there hasn’t been enough action on issues like the environment, the education system and digitalisation.

“These things came together and despite the good image Merkel had in international affairs, the people here said: ‘no, we are fed up of 16 years of (a CDU/CSU-led) government.'”

Younger people are voting Greens… and the Free Democrats

Another interesting takeaway from this election is: the kids want change. Okay, they’re not that young, but the 18-30s are definitely voting differently from their elders. Which isn’t surprising of course, but it’s interesting to look at why they’re voting the way they are.

The Greens were the party of choice for the under 30s in this election, according to analysis. The next most popular party for the younger people was the business-friendly Free Democrats (FDP). The SPD were next in line. As you can see from the graph below, the CDU/CSU, AfD and the Left Party didn’t really inspire the younger generations.

Die unter 30-Jährigen wählen Grüne und FDP auf Platz 1 und 2 #btw21 pic.twitter.com/1D9BLeLTi6

— Dominik Rzepka (@dominikrzepka) September 26, 2021

So what is it about the Greens and the pro-business Free Democrats that’s catching the imagination?

The Greens got many people’s vote because of the climate emergency.

“Climate is an issue that’s important all over the society, but for older generations it isn’t the top issue,” said Neugebauer. “For the under-30s climate change is the top problem.”

Younger people are voting for Christian Lindner’s Free Democrats because of the pro-business, modernisation and individualism stance.

“FDP is the party of entrepreneurship, freedom and so-called anti-state behaviour,” said Neugebauer. “They say individual interests have to have a preference ahead of state interests. And so far many younger people are less interested in the state telling them what to do – they want to decide for themselves.”

Your average young FDP voter would likely, for instance, be working at a successful startup in a city, and be earning a very nice wage.

In recent years, the FDP has been growing in confidence in opposition as well as gaining visibility with its vocal opposition to the government’s pandemic restrictions.

The party was especially popular with first-time voters on Sunday, winning 23 percent support from them – a tie for first place with the Greens, reported AFP.

Both the Greens and the FDP did even better than that among under-24s in the actual exit poll: https://t.co/P2vKgWsQhX I don't have a complete answer yet but I think there is a sizeable group of young voters who favour free enterprise but regard the CDU as a party for old people pic.twitter.com/aGFid71PIz

— Oliver Moody (@olivernmoody) September 27, 2021

As Neugebauer points out, older voters are still dominating the election results.

“The 18-30 year-olds have a lower share in the electorate than the elderly voters,” he said.

Watch this space to see how this plays out in the coming years.

The Left Party crashed and burned

The far-left Die Linke party is another of the big losers in this election. With 4.9 percent, it’s almost halved its result from the 2017 vote – and missed the 5 percent threshold to get into the Bundestag. It is able to enter parliament, however, by securing three direct mandates. What the hell happened?

In an analysis, the Tagesschau’s Uwe Jahn said divisions in the party may have contributed to the failure, as well as the party’s delayed party conference which was postponed twice due to the pandemic.

But perhaps other parties simply offered something more appealing to former leftist loyalists? This time around, more than a million Left voters migrated to the SPD and the Greens, Tagesschau reports.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments