In Italy, the decline in female employment during the Covid emergency was double the EU average, with 402,000 jobs lost between April and September 2020.

Last December alone, 99,000 women in Italy lost their employment, versus only 2,000 men in the same month, figures from Italian statistics office Istat showed.

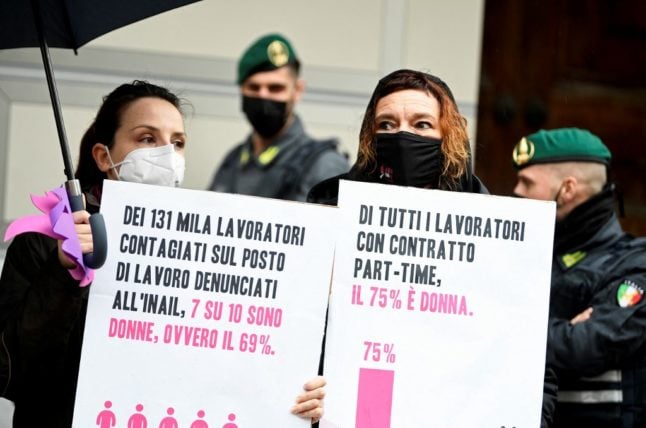

Economists say women in Italy have been disproportionately hit by job losses as they’re more likely to be precarious workers on short-term contracts, employed in service industries, such as in tourism or catering, which have been particularly badly hit by the coronavirus pandemic.

While it’s too early to see the full impact of the crisis on womens’ employment, it’s already clear that the pandemic has exacerbated long-existing problems with gender inequality in Italy’s labour market.

In 2019, fewer than half of working-age Italian women were in employment, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, even though women make up more than half of all Italians getting a bachelor’s degree or PhD.

In Italy, as in many other countries, the pandemic has highlighted the fact that the bulk of household and family responsibilities still often falls on women.

“From lost jobs and the growing wage gap, to the increase in unpaid care jobs and an increasingly absent welfare state, this pandemic is setting women back a few years, if not decades,” writes financial daily Il Sole 24 Ore.

In May, a WeWorld survey carried out at the end of the first lockdown reported that one in two women had given up at least one job due to the pandemic, and 31% had cancelled or postponed a job search.

This figure is “not surprising”, Il Sole 24 Ore writes, “since only 21% of part-time or job flexibility requests, presented by workers with young children, was approved.”

It said female employees were struggling with “the difficulty of reconciling work with family responsibilities during the time of the pandemic.”

But even before the pandemic, data shows new mothers were either quitting or losing their jobs at an alarming rate.

In 2016, one in four Italian women lost her job within a year of giving birth, according to Istat – and the risk increased with each child, the study found.

Womens’ low participation in the workforce and the chronically low – and falling – birthrate in Italy are two issues which have long been intertwined, and are both now worsening due to the pandemic.

READ ALSO: Italy’s low birth rate ‘plunging further due to coronavirus crisis’

In 2019, Italy recorded its lowest birth rate for more than 150 years, as births fell to 435,000. This trend continued in 2020, with a 1.57% decline compared to the previous year.

Successive Italian governments have in the past failed to prioritise policies on affordable childcare and financial support for new parents, meaning many young Italian women were having to choose between family or career.

In the past year, the previous Italian government has taken some steps towards improving the economic situation for new parents, mainly by extending child benefit schemes and raising paternity leave from five days to seven, and then to ten – meeting the EU’s recommended minimum.

The 2021 budget included extended financial support for families with children, most notably in the form of child support benefits available for new parents: the ‘Bonus Mamma Domani’ and the ‘Bonus Bebé’.

READ ALSO: Italy’s ‘baby bonuses’: What payments are available and how do you claim?

Italy’s new prime minister, Mario Draghi, acknowledged last month that closing the gender gap at work, particularly in the south of the country, would be key to restructuring Ital’s economy after the crisis.

“Italy today has one of the worst wage gaps between genders in Europe, as well as a chronic shortage of women in senior managerial positions,” he said.

Gender equality means “rebalancing of the wage gap and welfare system, beyond the choice between family and work,” he said.

However his government has not yet made any firm policy announcements on the issue.

“Leaving women behind puts a brake on growth, it means leaving the whole country behind.” Linda Laura Sabbadini, director of Istat, told Il Sole 24 Ore.

“The Bank of Italy has already shown that the increase in female employment brings with it an increase in income, and is an important element of protection from poverty.”

But the causes of the problem are deep-rooted and go beyond the purely practical or financial, experts say.

Paola Mascaro, head of a G20 working group created to identify best practices to support female leadership, said that on one hand “there is the lack of infrastructure, which some companies have tried to compensate for by providing nurseries and benefits.”

“Then there are cultural barriers, which refer to the patriarchal model in the background, which views work as more important for men than for women, and ensures that the burden of care remains 75% on the shoulders of women.”

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments