The once-obscure law professor has been at the helm of two governments of different political persuasions since 2018 – and may now be about to form a third.

READ ALSO: Italian PM Conte to resign in hope of forming new government

“I think he has rather uncommon qualities … otherwise he would not have got to where he is, and above all stayed there, despite all odds,” remarked political journalist Francesco Bei.

For the past few weeks, 56-year-old Conte has been fighting for his government's survival after former premier Matteo Renzi withdrew his small Italia Viva party from the ruling coalition.

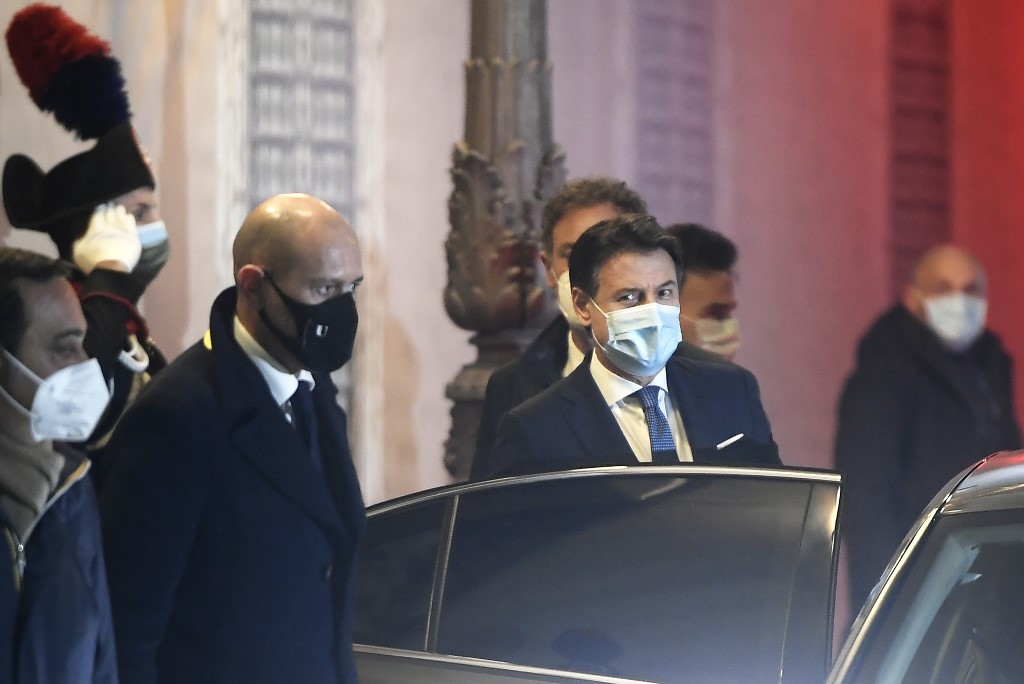

Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte (C) leaves Palazzo Madama, the Senate building in Rome, on Tuesday after narrowly winning a confidence vote. Photo: Filippo Monteforte/AFP

On Tuesday, Conte is set to offer his resignation to President Mattarella.

But Conte has enjoyed approval ratings topping 60 percent during the pandemic, and has seen his influence grow at home and abroad after his approach of locking down Italy was watched closely, and then followed, by governments across Europe.

“Populist puppet”

Conte was dubbed “Mr Nobody” when he was appointed in 2018 to take over a fractious coalition comprising the initially anti-establishment Five Star Movement (M5S) and Matteo Salvini's far-right League.

He introduced himself as “the people's advocate”, and said he was happy to lead a populist government if that meant listening to people's needs and working “to remove old privileges and entrenched powers.”

In the first few terrifying months of the pandemic, the seemingly unflappable Conte appeared to many Italians as a safe pair of hands.

“Let's keep our distance today, so that we may be able to hug each other with more warmth tomorrow,” he said at the start of a national lockdown in March.

Photo: AFP

With Italy the first European Union country to be hit badly, Conte leveraged the crisis to plead for more solidarity and eventually secured the largest slice of a 750-billion-euro ($906 billion) EU recovery fund – worth around 200-billion-euros ($196 billion).

Conte's approval ratings surged to 65 percent, according to an Ipsos survey for the Corriere della Sera newspaper.

In January ratings were still in the mid-50s – despite some signs of popular impatience with him.

Renzi has accused the premier and M5S of squandering the EU funds and failing to have the vision to spend it well.

READ ALSO: How Italy plans to spend its €222 billion coronavirus recovery fund

Critics also claim Conte hesitates over key decisions and failed to use the lull in infection rates last summer to prepare for a second wave that has proved deadlier than the first.

'Devout Catholic'

Born in 1964 in the tiny village of Volturara Appula in the southern region of Puglia, Conte was a law lecturer at the University of Florence.

A devout Catholic and former leftist turned M5S supporter, he also taught at Rome's Luiss University – although he has been accused of inflating parts

of his CV.

Conte is reportedly “very religious” and devoted to mystic Catholic saint Padre Pio, who was famous for exhibiting “stigmata”: body marks supposedly

matching the crucifixion wounds of Jesus Christ.

Of his own politics, he once said: “I used to vote left. Today, I think that the ideologies of the 20th century are no longer adequate.”

Photo: AFP

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments