“The prosecutor intends to take a decision concerning prosecution matters in the Palme investigation before July 1st,” Sweden's prosecution authority said on Friday morning, adding that the decision would be announced at an online press conference – date to be announced – due to the coronavirus pandemic.

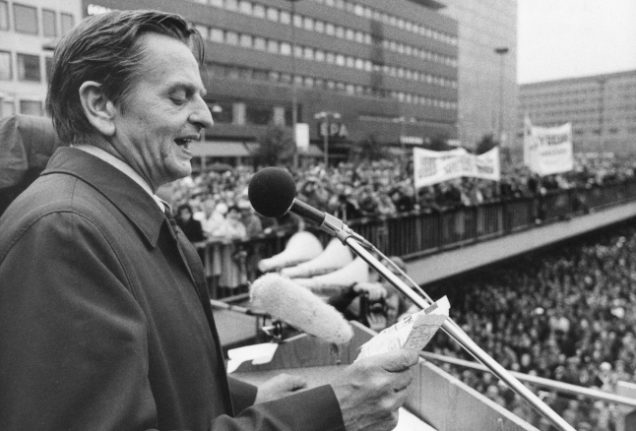

The charismatic Social Democrat premier Palme was gunned down in the street on February 28th, 1986, after leaving a Stockholm cinema with his wife, a killing that sent shockwaves through Sweden.

The gunman ran off with the murder weapon, and despite more than 10,000 people being questioned and more than 130 people claiming responsibility for the crime, the case has never been solved.

Chief prosecutor Krister Petersson took over the investigation in 2017, and told Swedish media earlier this year that he would bring the case to a conclusion this summer.

“I am optimistic about being able to present what happened with the murder and who is responsible for it,” prosecutor Krister Petersson said on Swedish public broadcaster SVT's programme Veckans Brott back in February, but did not say whether he believed he would bring charges against the suspect.

This could mean that Petersson believes the person responsible has since died, or it may be that the investigation will be closed. It is still not known whether the decision to be presented before July 1st will be to press charges against a suspect, to name a now-deceased suspect, or to drop the investigation completely.

Huge efforts have been made to track down Palme's killer in the past three decades. Sweden even removed the statute of limitations for murder cases back in 2010, partly so that the investigation could continue.

Police were criticised for their actions in the early stages of the murder probe, including failing to cordon off the scene promptly, which could have meant potential forensic evidence was destroyed. The bullets were found by a member of the public, and the gun used in the murder was never found.

Over the years, there have been many theories about what may have happened, which have suggested both individuals and groups as potential perpetrators.

A man named Christer Pettersson, who had a previous conviction for manslaughter, was in 1988 convicted of the murder after Palme's wife Lisbet identified him in a lineup. But he was later acquitted by a court of appeal, and died in 2004.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments