“With great sorrow we received information about the death of Kazimierz Albin, the last living survivor of the first transport of Poles to the German Auschwitz camp (No. 118),” the Auschwitz Memorial said on its official Twitter site.

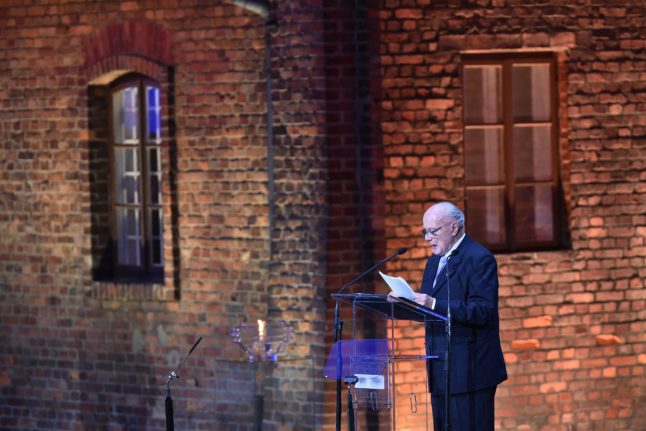

With great sorrow we received information about the death of Kazimierz Albin, the last living survivor of the first transport of Poles to the German Auschwitz camp (No. 118), a friend of the Memorial, a long-term member of the International Auschwitz Council. He was 96 years old. pic.twitter.com/24VyjSfsdE

— Auschwitz Memorial (@AuschwitzMuseum) July 23, 2019

Born in 1922 the southern Polish city of Krakow, Albin was arrested by the Nazis in January 1940 in Slovakia where he had fled after Germany occupied Poland in 1939.

Albin had been on his way to join the Polish Army then forming in France to fight the Nazis.

On June 14, 1940, he was deported to Auschwitz with the first convoy of Polish prisoners.

Their forearms were tattooed with the camp's notorious identification numbers ranging from 31 to 758. Albin was tattooed with the number 118.

He was one of the 140,000 to 150,000 non-Jewish Polish prisoners in Auschwitz, half of whom died there, according to Auschwitz museum estimates.

Albin survived because he managed to escape on February 27, 1943 along with

six other prisoners.

“It was a starry night, around minus 8 or minus 10 degrees Celsius outside,” Albin recalled in a 2015 interview with AFP.

“We took our clothes off and were half way across the Sola River when I heard the siren… Ice floes surrounded us,” he said, referring to a waterway passing through the southern Polish city of Oswiecim where Nazi Germany built

Auschwitz. Once free, Albin caught up with the Polish resistance.

Escapes from Auschwitz were rare. Of around 1.3 million people sent to the camp, only 802 — including 45 women — tried to flee, according to estimates from the museum.

Only 144 succeeded, while 327 were caught. The fate of the remaining 331 is

unknown.

After the war, Albin studied at the aviation department of the Krakow Polytechnic School to become an engineer.

He was a member of the International Auschwitz Council, an advisory body to the Polish prime minister that looks after the memorial site.

Nazi Germany killed some 1.1 million people, including one million European Jews, at the Auschwitz-Birkenau twin death camps before their liberation by the Soviet Red Army on January 27th, 1945.

SEE ALSO: Record numbers visit Auschwitz in 2018

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments