In the online realm, at least, the stigma around mental health is finally beginning to lift. Discussions about what constitutes self-care abound, and celebrities are opening up about their own experiences – being in the public eye is rarely kind to the psyche, after all.

Neither, as it turns out, is leaving one’s home country and starting afresh. Berlin is much idealized as a place of refuge. Even if a Wahlberliner (Berlin newcomer) isn’t escaping immediate threats of war or persecution, they are usually still looking for a seismic change in their lives. As Stuart Braun writes in City of Exiles, his historical account of Berlin’s migrants, it is “that rare 21st century city in which you can still be an alien,” a place to lose yourself in art and the infamous nightlife.

But narcotics, hallucinogens and the pressures involved in making a fresh break can rub up against the harsh reality of daily Berlin life and the city's cold, bleak winters.

For new Berliners from foreign countries, the national statutory health insurance is often ill-equipped to deal with their problems.

While hospital admissions for depression have soared in Germany since the start of the century, waiting times remain stubbornly high. A report from 2011 estimated that the average person in Germany must wait three months for an initial appointment with a registered psychotherapist, then three more months until a spot for regular therapy sessions opens up – which in some cases is a fatally long time.

“Kafkaesque” is bandied about when describing German bureaucracy, but when it comes to the health system, the term carries some weight. If you’re a salaried employee, you’ll be insured with your statutory health provider – unfortunately though, there is no guarantee of finding the right therapist on public insurance, especially for those who require foreign language services.

While there are some array of registered private multilingual therapists in Berlin, this is often a socially exclusive solution. In order to receive treatment, a patient already on public insurance must generally pay out of their own pocket for healthcare that should be covered as a standard part of their salary, making psychotherapy a luxury.

Victoria,* 26, has experience in paying double – she decided to see a private English-speaking counsellor as the waiting times on the public system were too long.

“I ended up paying more than €100 per hour, which I could only afford for a short time. I know for many others it wouldn’t be affordable at all,” she told The Local.

She also wonders about cultural differences when it comes to therapy.

“I’d had counselling before in my home country and so was quite sure about what works for me, which is CBT [cognitive behavioural therapy]. But this doesn’t seem to be so common here, which I think is where people from English-speaking countries feel less supported.”

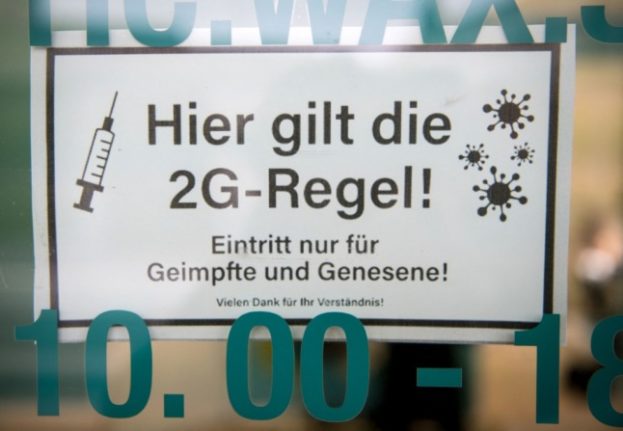

Photo: DPA

Photo: DPA

'People flock here with massive expectations'

The increasing international population in Berlin seems to be negatively correlated with the number of psychotherapists equipped to carry out their work in another language, or treat the particular issues attached to being an expat.

It’s not just expressing yourself in your native language that’s an issue – indeed, many non-native English-speaking new Berliners with little or no command of German will turn to an English therapist. The underlying problem seems to be the lack of therapists who understand what it is like to feel lost and alone in a new country.

So just like the tradition of soul-searching misfits in Berlin, when it comes to therapy, people are ripping up the system and starting over in response to their frustration with brimming waiting lists and the financial burden. Experienced in their native countries but shut out by Berlin bureaucracy, they are offering therapy services on their own terms: affordable, flexible, and in a familiar language.

“I hear repeatedly that there are way too few available English-speaking therapists in Berlin, given the sheer number of people from around the world living here. A lot of us have the right skills, and Berlin needs to accommodate this,” says Lauren*, an Australian 20-something with a degree in social work under her belt.

“Isolation due to drugs, or unexpectedly hostile attitudes towards those on the LGBTIQ spectrum” have led to a high demand for counselling services among foreigners, she believes.

Like in Hollywood, people “flock here with massive, hedonistic expectations that come crashing down…”

“People turn to each other [on] Facebook groups, in an attempt to get answers.”

Between childcare and call centre work, Lauren provides “black market” counselling services paid in cash: €20 per hour. She’s tried in vain to make it legit.

“Everything required a Master’s or higher. There are rigorous social care and psychology bodies in Germany, and you need insurance for therapy. So I decided to call myself more of a lending ear, a life coach,” she says.

Kristen’s* private insurance didn’t cover psychology. The 36-year-old freelancer started to see another “black market” professional: a psychologist who provided English therapy on a sliding-scale basis, but whose training in another European country meant she could not join the German system.

“She charged me €40 an hour, cash in hand. We conducted our sessions in my home, her home, parks, or cafés. It worked for me.”

18 months later, Kristen’s life circumstances had changed and she was on the statutory health system.

“My GP showed me a website with public English-speaking therapists in Berlin. I contacted each one and was either declined or waitlisted.”

“Apparently you can take five of these rejections to your statutory health provider and make a case for why they should reimburse you for a private therapist, on the condition that you are already taking those therapy sessions and paying upfront – but they could decide not to reimburse you. The financial gamble is just too much when you’re already dealing with mental stuff.”

The absence of bureaucratic restrictions in black market therapy, and tips shared in online groups from those going through similar issues means that those affected can feel listened to and helped, with little or no waiting time.

This is also something that can apply to asylum seekers. Despite many refugees suffering trauma and isolation due to the experiences of fleeing war, they still generally wait a long time for appointments.

“We cannot offer second-rate treatment to those who come to us for protection, therefore the removal of barriers to healthcare for refugees and traumatised people needs to be talked about,’ says Sibel Atasayi from BAfF, an organization facilitating psychological support for refugees and torture victims. “From a humanistic and professional perspective, we welcome people offering help to the vulnerable, whatever form it may take.”

Germany’s suicide rate in 2015 was more than triple the number of road fatalities in the same year. The fragility of the subject means that people may be hesitant to talk about it, but in the end, only the existence of accessible resources can diminish the suffering that poor mental health brings about – and as the country’s population diversifies, so must the range of help on offer.

Whether Berlin will yield to the demand to refine its formal services remains to be seen – and it could be the question that defines its future as Europe’s big migrant city.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Please whitelist us to continue reading.

Member comments